AMD: Can It Really Make 10X?

AMD is killing Intel and chasing Nvidia. It's a great company with a great management. But can it really make 10x?

I have been researching AMD for three weeks and I have to warn you:

🚨This is a different kind of write-up on AMD.🚨

It is a complicated business in a complicated industry.

This is going to be a sometimes challenging read.

Yet, I have simplified it so much that everybody will understand.

Most importantly, you will understand the business from its A to D.

Plus, you will have fun reading it. Let’s get started!

In all ages, there has been one place on earth that exerted a disproportionate influence on human development, on how we think, on how we live…

It was Athens in ancient times. Indeed, most of our basic institutions today, like democracy, come from Athens.

It was Baghdad in Medieval times. Al-Khwarizmi used algebra to solve quadratic equations and perhaps paved the way for the future discoveries in physics.

It was Florence in the Renaissance. Within 100 years, the most influential artists in history lived there: Leonardo Da Vinci, Donatello, Michelangelo, Raphael…

All these centers emerged in a similar way: Favorable environment combined with a starter figure.

It was the pluralistic environment created by the city states and Plato in Athens; in Baghdad, Abbasid Ruler Al-Maʾmūn encouraged the translation of Greek philosophical and scientific works and created a welcoming environment for scientists and artists from all religions; in Florence strong families like Medicis who created their wealth through banking and trade simply opted in to be patrons to artists like Leonardo Da Vinci.

Raphael’s famous work “School of Athens” proves the point.

It’s remarkable that the artwork features Plato and Aristotle at the center and fellow philosophers and students surrounding them in Athens while Raphael himself was a Renaissance artist who lived among others like Leonardo Da Vinci and Michelangelo.

Once a conducive environment meets its influential starter figure, it attracts like-minded people like a vortex and this evolves into a virtuous cycle that maintains itself.

For the past 100 years, since the 1950s, this place has been the Silicon Valley.

There is a reason it’s called Silicon Valley. It’s because what created it is the invention of “integrated circuit” or “chip”. It’s also called silicon because the main semiconductor material used to make it is silicon.

As other disproportionately influential places in history, Silicon Valley was also a result of its own conducive environment and influential starter figure.

The area centers on Stanford University, from which William Shockley’s mother May graduated. Later, his son would also follow her and attend California Institute of Technology and get his PHD from MIT.

Shockley invented the transistor as we know it in Bell Labs and later returned to the Valley and established “Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory” in Mountain View. This was the first establishment working on silicon semiconductor devices in the area.

With Shockley’s establishing his lab in Mountain View, everything was ready for area to become like Athens in ancient times or Florence in Renaissance:

Influential figure like William Shockley.

World class research university, supplying world class talent.

US Government pouring money in tech projects to stay ahead of the Soviets.

Soon, Shockley was hiring other geniuses to work with him. Among them were young researchers like Robert Noyce, Gordon Moore and Eugene Kleiner.

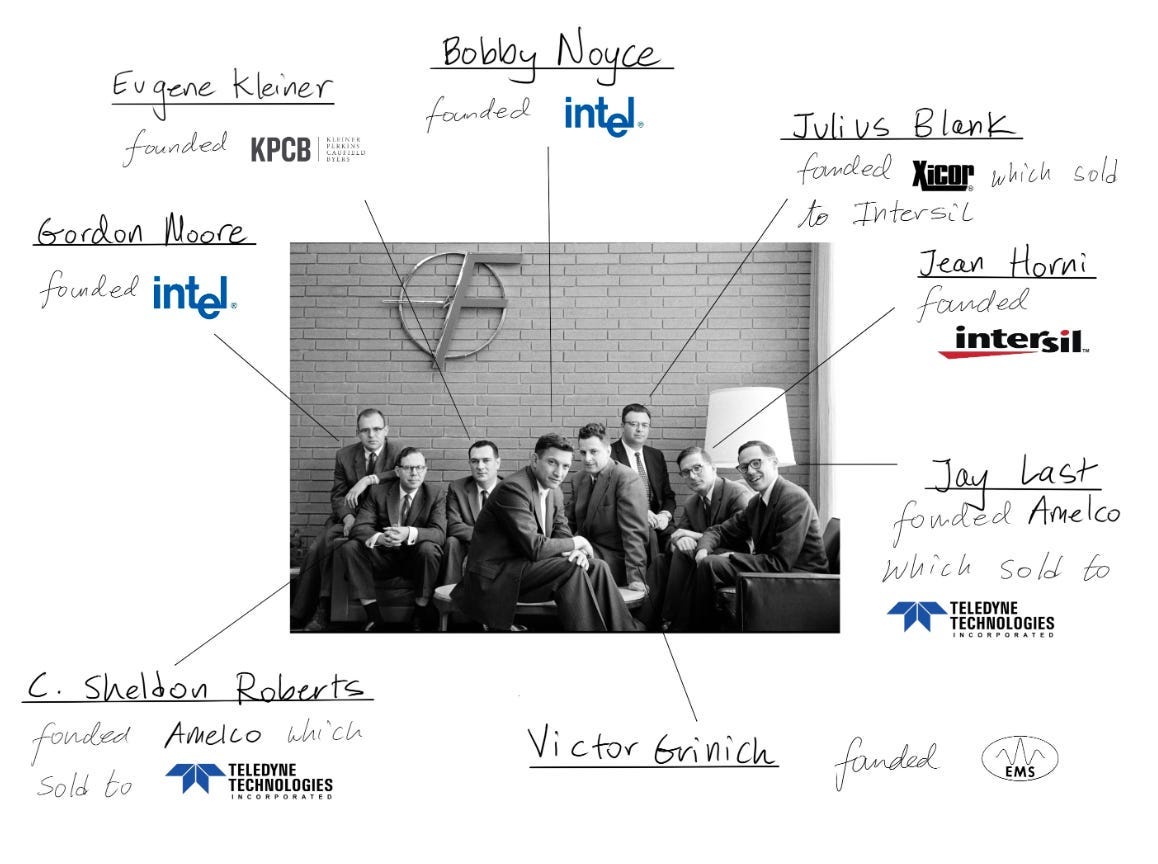

Though a brilliant scientist, Shockley was a very bad manager. He was autocratic, domineering, erratic, hard-to-please, and increasingly paranoid. Couldn’t take this anymore, a group of 8 researchers resigned from Shockley Labs and founded their own company: Fairchild Semiconductor.

Fairchild would become the Valley's main incubator. People working in Fairchild or closely related to it would later found many companies in Silicon Valley. In this sense, it’s the original of the PayPal mafia.

Its spin-off companies came to be known as "Fairchildren" and included Intel, Precision Monolithics, Signetics and of course Advanced Micro Devices, or AMD.

Today, only two of these companies are relevant to us: Intel and AMD.

AMD, despite the cutting edge competition in silicons, has survived and thrived through:

Commoditization of memory chips.

Rise of advanced logic chips called CPUs.

Pivot to the fabless model and focusing on design.

And now the rise of parallel computing: GPUs.

While Intel has slid behind in this wave AMD has kept tabs on the leader, Nvidia, and has a shot to take market share from it as the GPU demand is expected to rise exponentially.

This is why I love it: Extreme adaptability through relentless innovation.

Yet, the stock is down 10% in the last twelve months while Nvidia is up 180%.

Thus the question before investors is simple: Is it time to bet on AMD?

This is what we are going to discuss today.

So, let me cut the BS and dive deep into AMD!

What are you going to read:

1. Understanding The Business

2. Moat Analysis

3. Investment Thesis

4. Fundamental Analysis

5. Valuation

6. Conclusion

🔑🔑 Key Takeaways

🎯 AMD successfully reinvented itself as one of the leading innovators in the market thanks to its sublet architecture and managerial perfection.

🎯 The market is extremely competitive and it’s very hard to build a durable competitive advantage. Yet, AMD has tools to stay ahead of the competition.

🎯 It’s operating in very fast growing markets with potential to increase its market share especially in dual core chips mainly used in inference workloads.

🎯 Its financial position is rock solid and it’s generating phenomenal returns on invested capital.

🎯 It looks fairly valued yet it promises above average returns in the next 5 years as the market opportunity ahead of it is gigantic.

🏭Understanding the Business

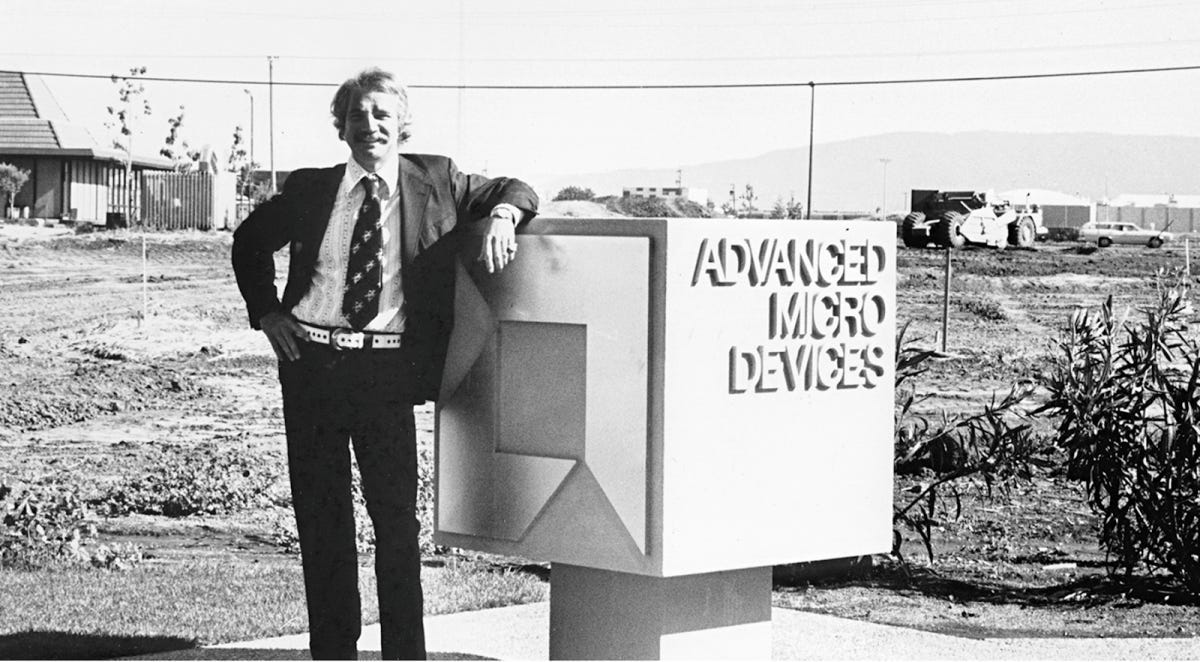

AMD’s story began similarly to the many other legendary chip factories: Personal disappointment.

Jerry Sanders III had joined Fairchild Semiconductor in 1961 as a young electrical engineer. But his career took a turn and he found himself as the Valley's most influential salesman.

He had long hair and liked to wear flashy suits. He was running all sales operations of Fairchild. After Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore left Fairchild in 1968, Sanders was confident he would take the top job.

He got passed over instead.

Disappointed, he decided to leave Fairchild and found his own company: Advanced Micro Devices.

Sanders wasn’t a regular salesman, he was an engineer by training and he understood that the semiconductor industry needed competition to develop further.

He raised $100,000 venture capital and took seven ex Fairchild employees with him. They were going to compete against the likes of Robert Noyce and Gorden Moore, the guys that started the industry.

Many thought this was an impossible task but Sanders had a plan. He knew he had to survive first. Instead of burning cash, he came up with a strategic plan to survive: They became a second-source manufacturer, essentially producing licensed copies of other companies' chips.

This was an amazing strategic move and perhaps the only way to keep a chip company alive without a technical genius like Robert Noyce. This allowed them to:

Generate revenue to take them off the ground.

Get blueprints of other designers and reverse engineer their chips.

Iterate on designs using the proceeds from its manufacturing business.

In 1970, it achieved a significant milestone with the release of its first proprietary product, the Am2501 logic counter.

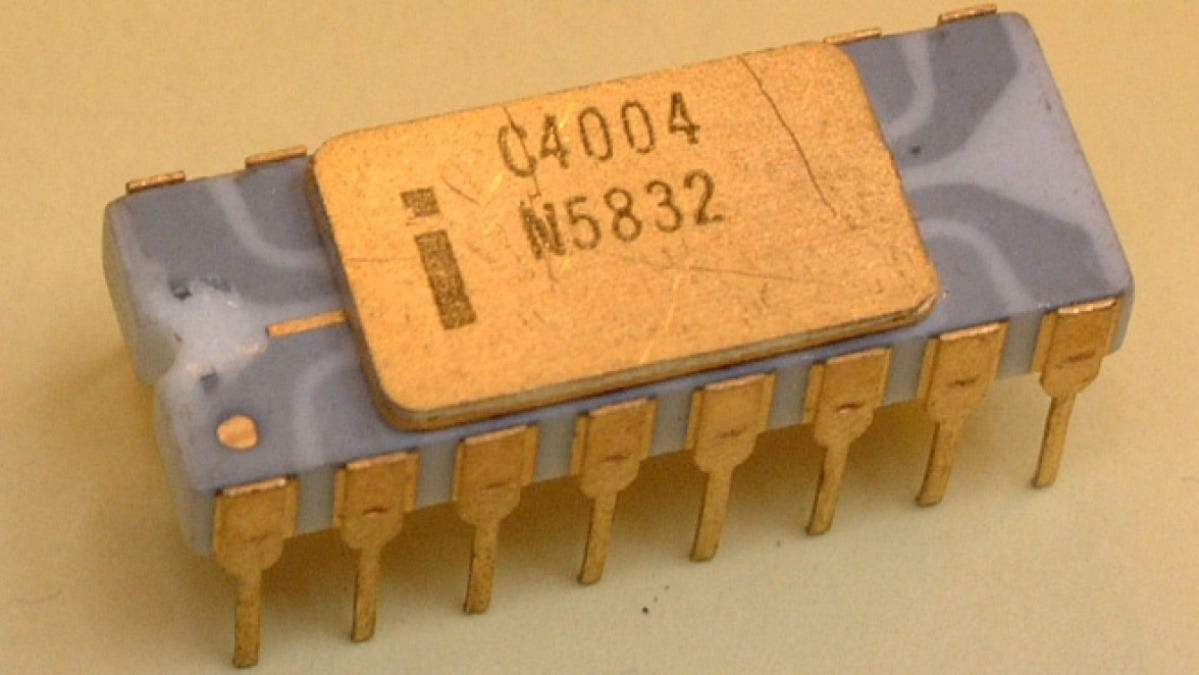

Though it was still far away from competing head to head with Intel. Led by Noyce and Moore, Intel had just created the first logic chip in the world, or CPU as we know it: Intel C4004.

Over the next few years, Intel delivered new iterations of this device - raising the output and cutting cost.

These include the 8008 in 1972, the 8080 in 1974, and the 8085 in 1976. A notable achievement was the 8080. Intel's second-generation microprocessor.

In 1975, a year after the 8080's release, AMD started producing its unauthorized second-source clone of Intel's market leading 8080 microprocessor: The Am9080.

It was a great business for AMD because those chips were cheap to produce and were sold to the military for as high as $700. This provided it with the revenue explosion needed to reinvent itself as an innovative designer.

It had survived and now it was establishing itself in the industry.

Yet it was still behind Intel in terms of native chip design capabilities. Intel came up with new CPUs based on x86 architecture in 1978. It was an industry defining moment and left AMD under the shadows.

However, fortune would knock on its door again in 1981 in the form of IBM.

Apple had pioneered personal computing in the 1970s, and in early 1980s IBM understood that it had to be in the PC market if it wanted to stay relevant. It wanted to use Intel x86 chips but on the condition that there was also a second source supplier. It wanted supply to be reliable.

Intel turned to an old partner: AMD.

Thus, throughout the 1980s AMD worked primarily as a second source supplier to Intel while it kept reverse engineering Intel designs and hired talent to iterate on them.

AMD’s patient reverse engineering of and iterating on Intel chips paid off in 1991. It launched AM386. By the end of 1992, AMD would produce 9.5 million of these chips, generating a billion dollars in revenue. It leapfrogged Motorola and established itself as the second largest chip company.

Yet, it wouldn’t be able to duly capitalize on this success.

The reason was simple: The nature of the semiconductor business was different then.

Companies were designing and manufacturing their own chips. This was a limiting factor. What you could design was basically limited by what you could manufacture. If you designed something that required a more advanced manufacturing process, you would also have to invest in manufacturing.

Intel had dominated the industry so long that it had resources to bear this double-cost structure, but AMD couldn’t.

The result? Intel was basically determining the pace of development. While Intel was pushing towards smaller transistors, AMD was struggling with yield issues in their existing processes.

This was the persistent theme in the next 20 years. Whenever AMD came up with a superior design, Intel would leapfrog it because of:

Persisting manufacturing issues.

High R&D spending to develop fabs.

Intel's superior manufacturing capabilities.

Intel's manufacturing budget was 5-6 times larger than AMD's entire revenue. It was like a middleweight boxer trying to outpunch a heavyweight. You can land a few good hits, but you'll eventually get knocked out.

This is why AMD kept getting on the verge of bankruptcy until the 2010s.

Then, came Lisa Su.

She did what many other visionaries had done: She focused.

Just as Steve Jobs cut 80% of Apple’s product line when he returned to the company, Su also rejected the common wisdom that AMD should compete with Intel in all categories.

She knew that she didn’t have resources to do that but she had what it takes to be a category winner.

She decided to focus on server CPUs. Why? Because server chips have:

Higher margins.

More stable demand.

Longer product cycles.

Yet, this was just the beginning. She did something else that really put AMD on the map: She outsourced manufacturing to TSMC.

This allowed AMD to focus solely on design. Su reasoned that manufacturing R&D would increase skyrockets and Intel didn’t have enough customers for the manufacturing arm to be self-sufficient. She thought that even Intel’s resources would fall short at some point from investing enough in both design and manufacturing.

This was pure genius.

As Intel struggled with its unprofitable foundry, TSMC invested all revenues back in business and created the most advanced foundry in the world. Allowing its customers to focus on cutting edge designs.

Result?

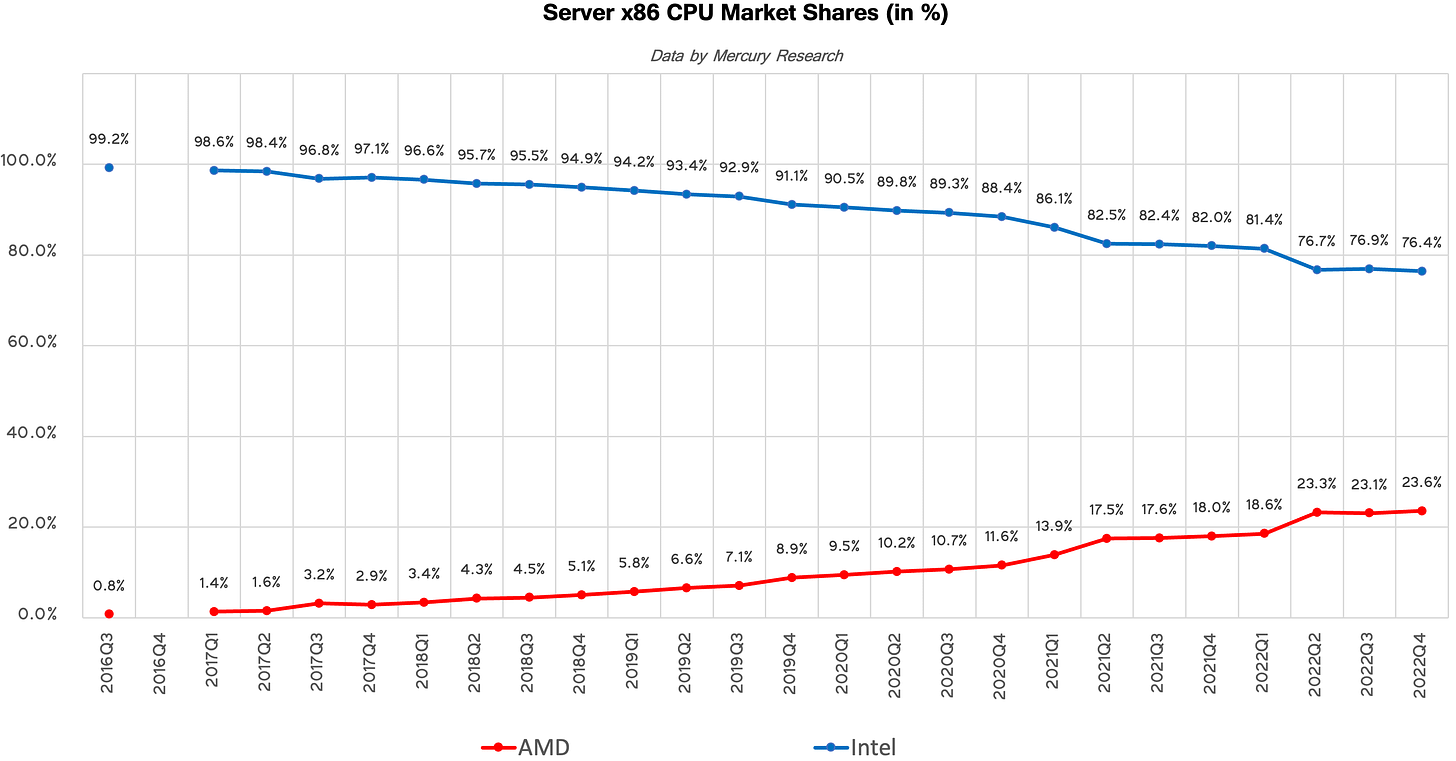

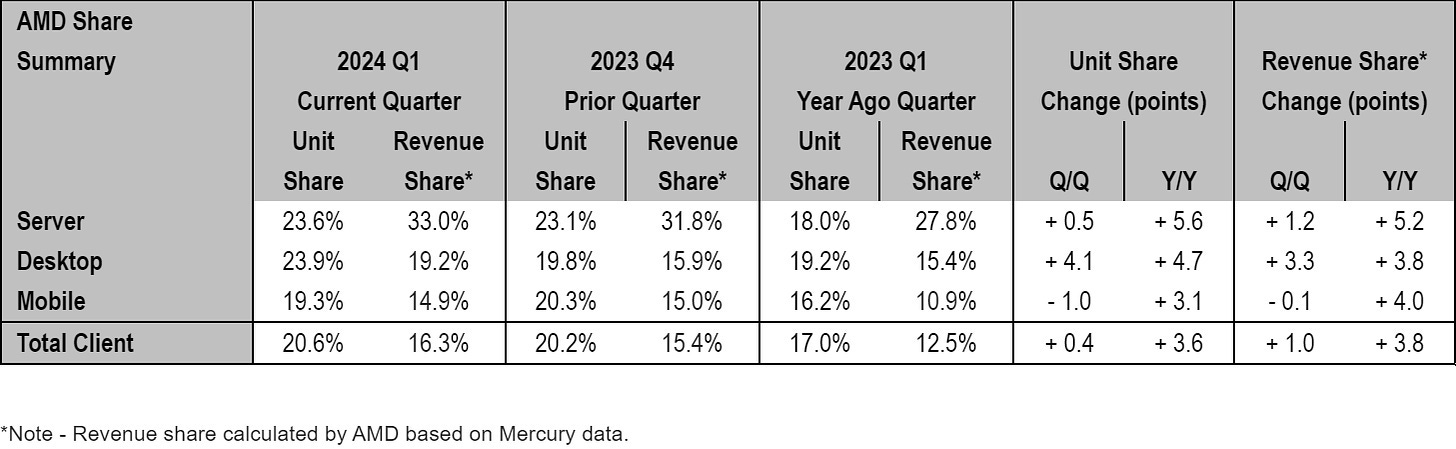

In 2016, AMD server business didn’t exist; at the end of 2022, it had 23.6% market share. Its current market share is still estimated at around 23% while revenue share jumped to 33.9%.

This is how you do it, literally.

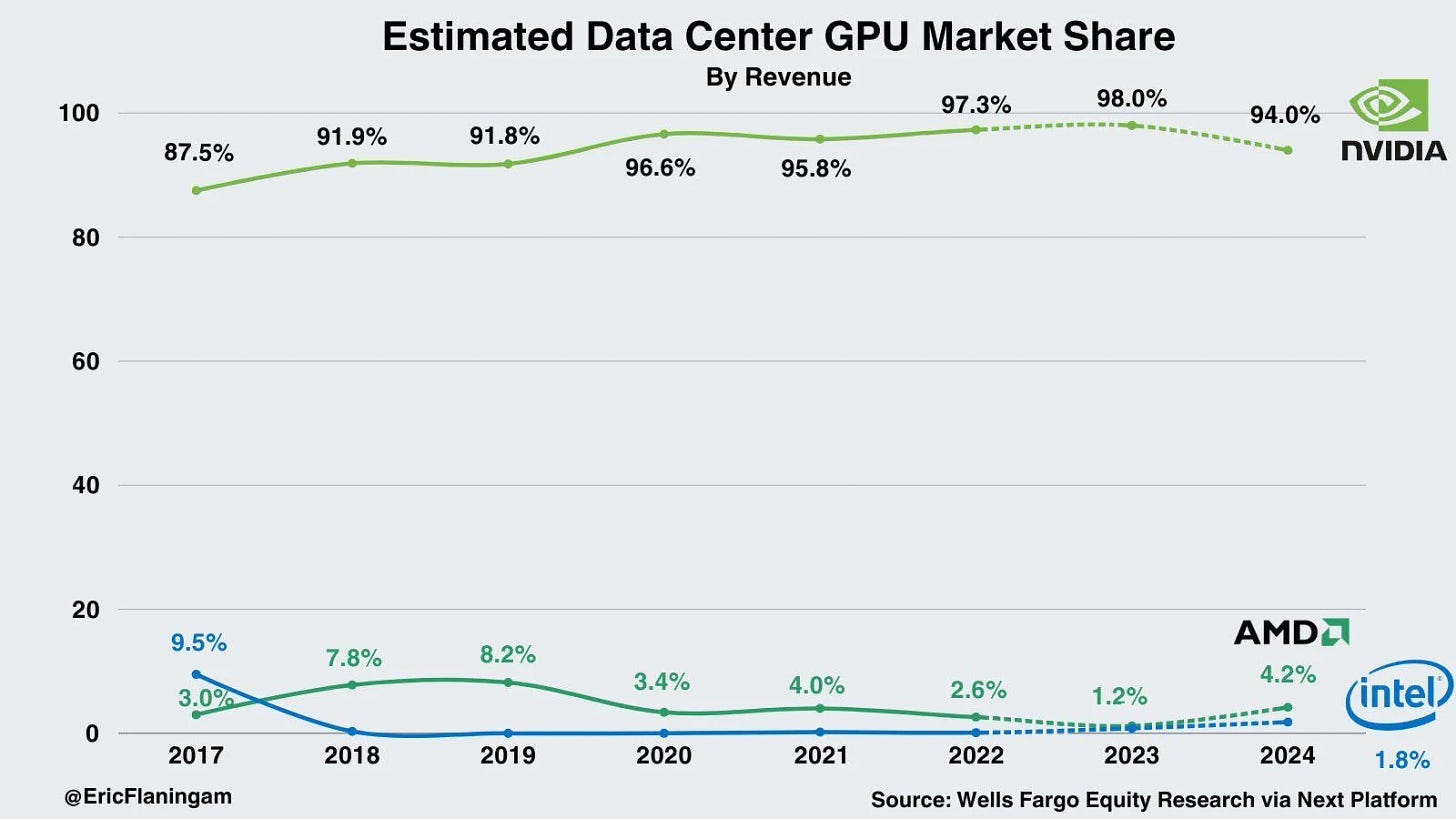

You can see AMD’s same reflexes play out in Data Center GPUs too. Nvidia is undoubtedly dominating this field, though AMD is showing reflexes while Intel doesn’t even show vitals.

As you see, Nvidia’s market share started to decline after it peaked at 98% in 2023. It’s obvious that 75% of the market share it lost went to AMD while Intel is standing there like a rounding error.

Now you have the whole story:

AMD started as a second source manufacturer.

It became a full fledged designer that outsources manufacturing.

It's mainly making CPUs but trying to carve out a place for itself in GPUs.

We now have a grasp on its business. However the historical context we have provided above wasn’t for nothing. It should have made you think that this is a chaotic and extremely competitive industry.

And guess what? Companies exposed to stiff competition don’t generally make great investments.

So we have to ask: Does it have a moat that protects it against the competition?

Let’s see.

🏰 Moat Analysis

The interesting fact with competitive advantage is that it manifests itself in different ways in different industries.

Take Coca-Cola for example.

For Coca-Cola, competitive advantage is a differentiated product that doesn’t require much investment. It’s natural because they don’t even need to improve the product. They have a product customers love and they have a monopoly over it. They can raise prices without losing many customers. There is nothing like a better or faster product.

In technology you can’t do that.

In tech, competitive advantage usually manifests itself as being able to stay competitive.

Take Apple as an example. It’s the most recognized brand in the world and has arguably the widest moat in tech. Yet, it only gives it an edge to stay ahead of the competition. It still has to invest, innovate, develop products and launch new ones.

If it stops launching a new iPhone every year, Samsung will pass it in a couple years.

This is even more intense in chips.

Thus, you have to first correctly understand the competitive advantage in this industry. It doesn’t mean being impervious like Coca-Cola, it means:

Low threat of total disruption.

Having tools to stay ahead of the curve.

Will the business survive? Is it well positioned to out-innovate competitors?

Answer to the first question is pretty straightforward: Yes.

Chip business is capital intensive. It’s not something that you can enter with a small business credit from your local bank. It requires billions of dollars, and PHDs from the top universities.

Why would they join a nascent chip company instead of joining Nvidia or AMD and see their stock options flow and make them incredibly wealthy.

They won’t. It’s not like software where you can create a viral product from your dorm room.

Who would be your manufacturer? How can you get TSMC to manufacture your chip while Nvidia, AMD and Apple book nearly all the capacity upfront. If you think you don’t have to work with TSMC, then probably your chip isn’t advanced enough. How will you sell a mediocre chip? You can’t.

This is a tightly knit industry protected by huge entry barriers. Incumbents are more likely to blunder themselves than getting disrupted by a new entrant.

Let’s get to the second question: Is it well positioned to stay ahead in the game?

Well, that’s a more complicated question.

Let’s don’t deceive ourselves: The most important factor in chip business is performance. Your clients don’t care about the brand on the chip or how it looks, they look for the performance.

But “performance” itself is a complicated term.

It’s not just computing power, many things go into this word: Ease of use, compatibility, manufacturing costs etc…

Cheaper your design to manufacture, more cost savings you will pass to your customers and in turn they will cut their prices to boost their competitive position in the market. Again, if it’s compatible with the existing networks and software, your customers will spend less time integrating it and in turn cheaper their end product will be.

So, to understand whether AMD has an advantage here, we have to ask: “How it leapfrogged Intel in performance?”

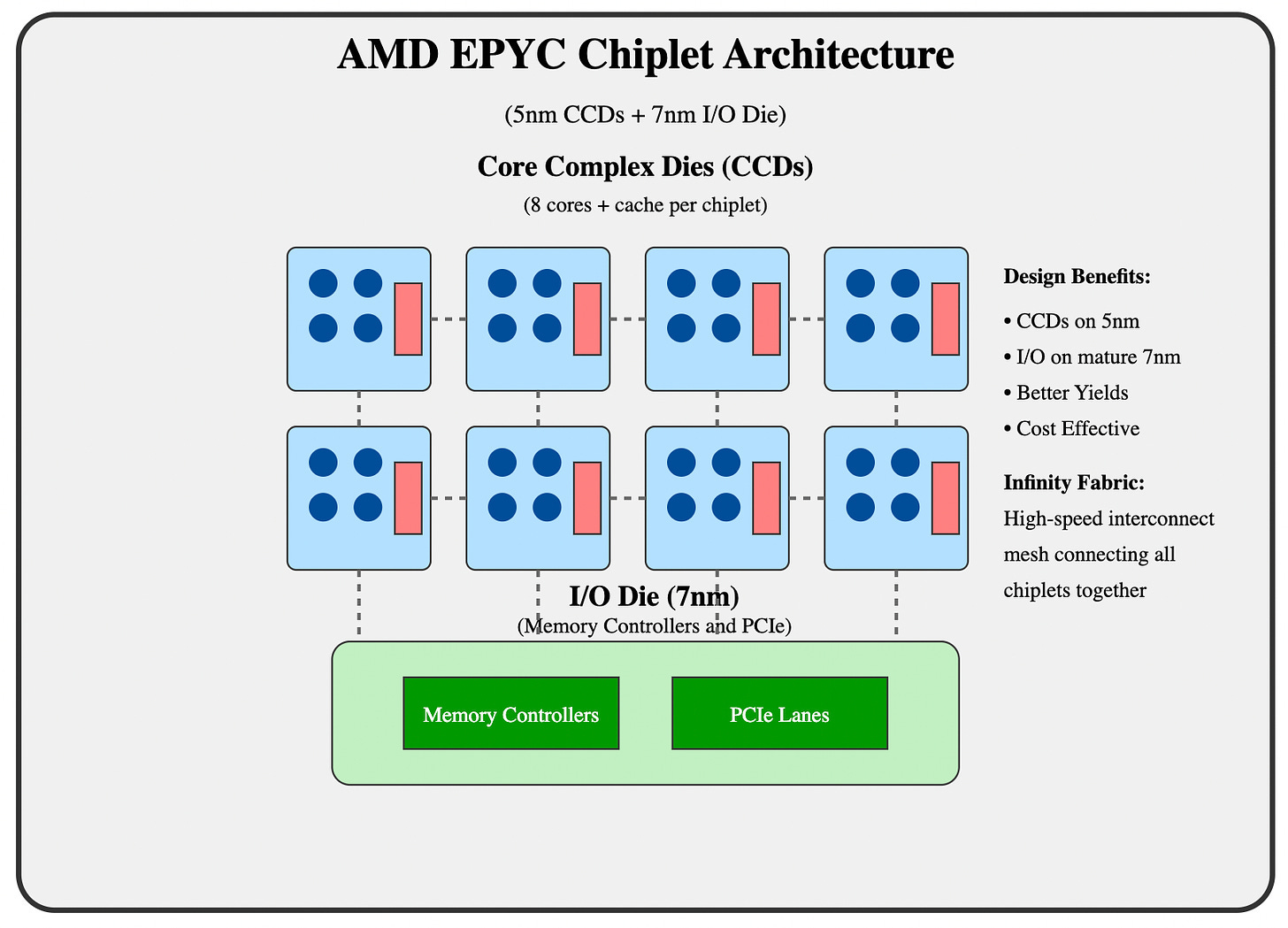

This has a simple answer: Chiplet design. But it has complicated implications. I will try to simplify this as much as possible.

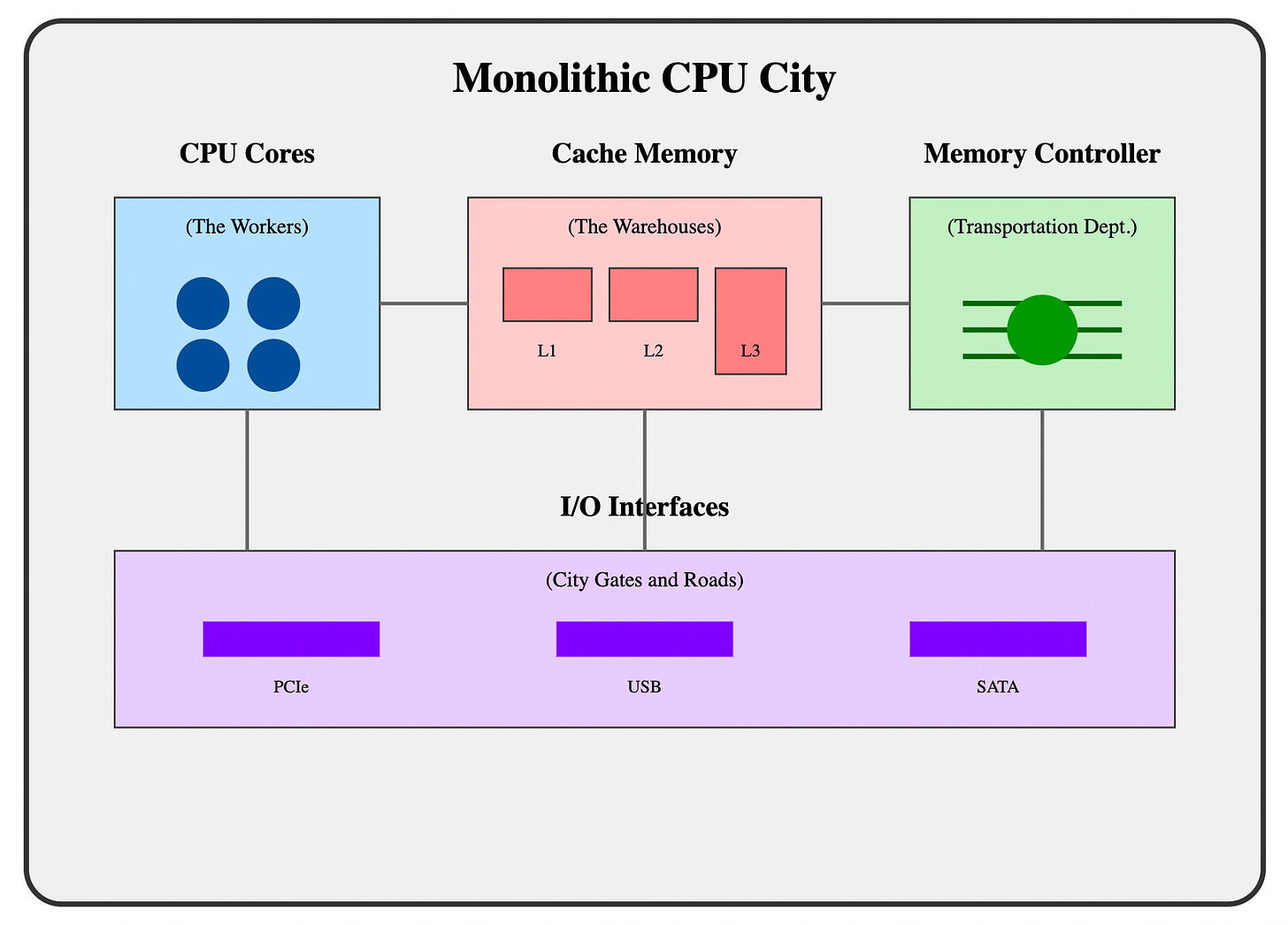

Basic chip architecture has three parts: Cores, caches, memory controller and I/O interfaces.

If you think of it like a city:

Cores: They are the "workers" of the city. They are the fundamental processing units that execute instructions from programs (like software applications). Each core can handle one task (thread) at a time.

Cache Memory: It is like a set of warehouses located within the city. They store frequently used materials (data and instructions) so the workers (cores) can access them quickly.

Memory Controller: It is like the city's internal transportation department. It manages the flow of materials (data) between the warehouses (cache) and the outside world (main memory - RAM).

I/O Interfaces: They are like the city's gates, roads, and communication systems that connect it to the outside world. They allow the CPU to interact with other components in the computer.

Traditionally designers used monolithic structure to create chips, meaning all these components – cores, cache, memory controller, I/O interfaces – are built on the same piece of silicon (the die). It's like a well-integrated city where everything is close together and communication is relatively fast.

Well, if you liken it to Manhattan Island in your mind, you immediately start to notice the increasing hardship with this design.

As the city (CPU) gets bigger and more complex, it becomes harder to manage and build. Traffic jams (communication bottlenecks) can occur. Building larger and larger cities becomes increasingly difficult and expensive.

This is where AMD switched to a new structure called “chiplets” and leapfrogged Intel.

As opposed to monolithic chips, chiplet design doesn't put everything on the same die. Instead, it uses parts built on different dies and connects them together with interconnects. It’s like, instead of putting the warehouses in the city, locating them outside the city but building advanced highways between the warehouse and city where cars can travel at very high speed without accidents.

As you see cores are on different dies in this design than the memory controller and the I/O interfaces.

This provides many advantages:

It cuts the intervals between iterations. AMD can keep using the same I/O die while changing only cores. In a monolithic design, you have to change everything.

It can create different products using different numbers and combinations of chiplets.

It can design and validate all chiplets independently as opposed to designing and validating them altogether in a monolithic structure. This provides a significant time to market advantage.

I/O dies could be manufactured using a less developed process like 7nm while only cores are manufactured on advanced processes like 5nm. This cuts manufacturing costs and increases yields.

AMD can achieve yields above 80% while competitors struggle with 60% on complex chips. This translates to significantly better economics.

This is how it leapfrogged Intel.

Couldn’t Intel do that too? Yes of course but it didn’t do that because it couldn’t overcome the innovator’s dilemma. It had a clear lead in designing monolithic chips and it thought it could forever rely on that dominance. It was dominating the game, but it didn’t see that there was a new game in town. It’s now switching to this design system and it calls it “tiles” instead of chiplets. Yet, the roles have changed and AMD has a superior position right now in this game.

AMD is a larger company than Intel now, it has a way better CEO, it’s hiring better talent and it’s laser focused on design while Intel still grapples with its foundry business and trying to play the catch up game in design.

This isn’t just useful in its competition with Intel, it also has great promises in the GPU race too.

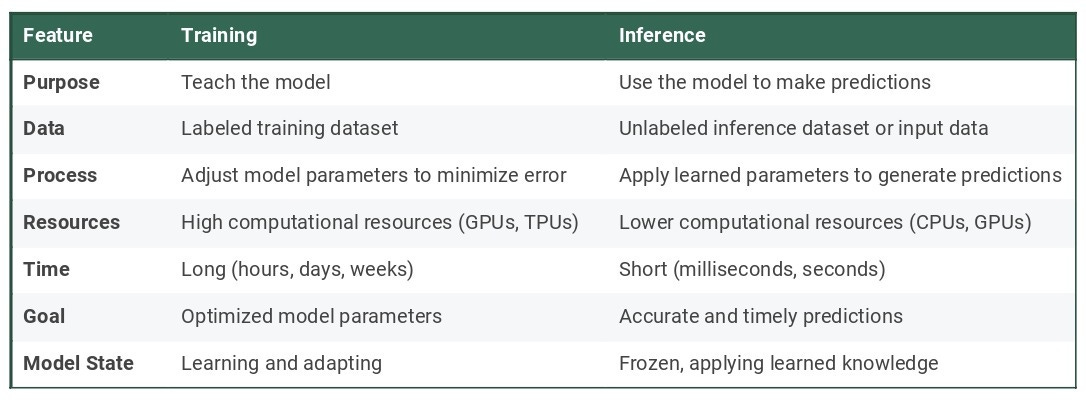

Data center GPUs are mainly used in training and Nvidia has an undisputed lead in this sector.

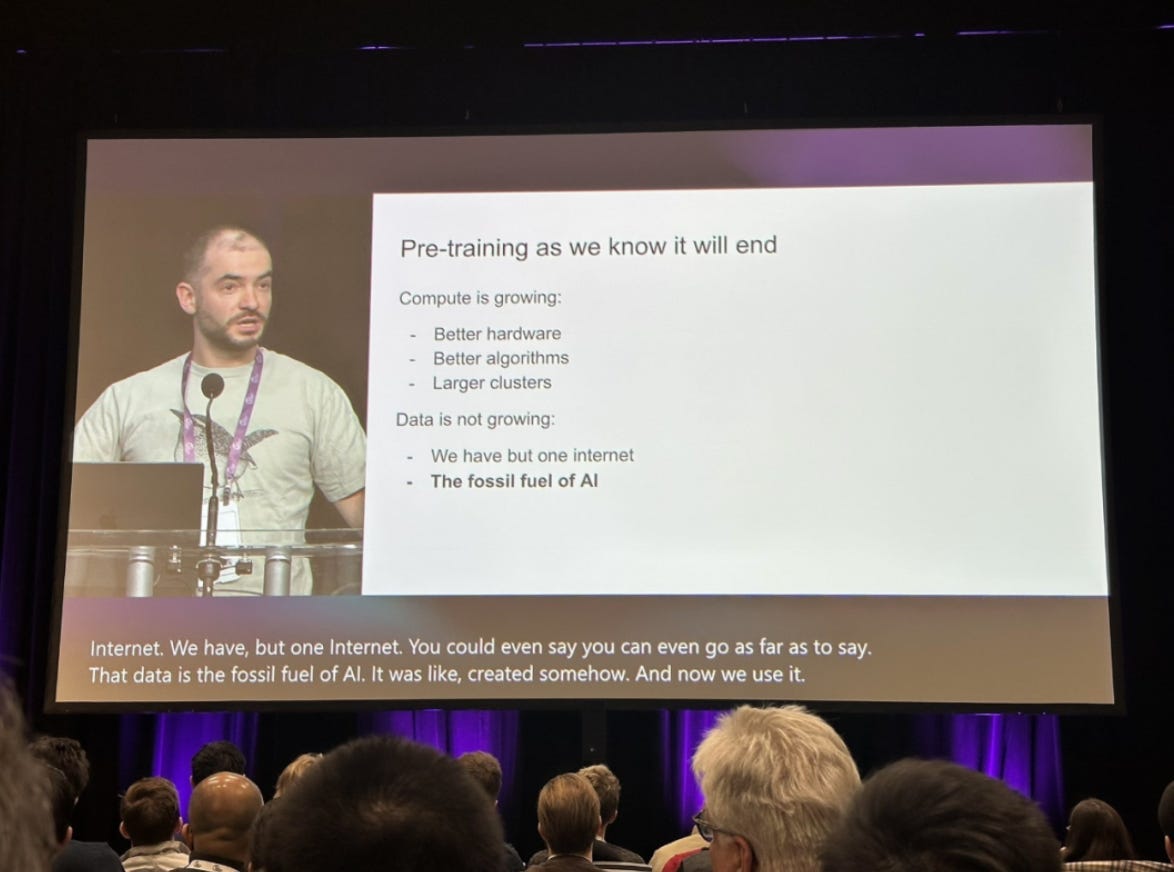

However, as Ilya Sutskever also put it, gains from the training phase are rapidly plateauing.

This means that there is very little to gain from better training the AI models because we have already trained them on all the knowledge humanity has created so far. The next phase is AI creating knowledge that doesn’t exist before and it requires better inferencing.

While training is GPU oriented, inferencing requires more involvement of CPUs. This is especially true for smaller models. Overall, the CPU is almost always involved in inference, at the very least for managing the system and handling data flow.

You might have started to get some ideas why AMD, in theory, can revolutionize this field.

Using its chiplet design, it can build AI chips that contain both GPU and CPU cores for faster inferencing like its MI300A chips. In this design, latency is also lower as you don’t need to link the GPU to outside CPU supporting it.

Not just that. Chiplet architecture can also give it an edge as monolithic designs become harder to implement and manufacture. We have seen this with Nvidia Blackwell. It basically used a chiplet design by connecting two H100s together but it experienced manufacturing problems and had to postpone delivery dates of the chips several times as it’s not used to chiplet architecture.

AMD has a clear advantage in implementing chiplet designs. Its MI300X is a state of the art GPU using chiplet architecture. So, in theory, it has a shot to gain some market share from Nvidia if it blunders at some point.

Overall, this is an incredibly complex and competitive industry. However, as we have seen, AMD managed to stay in the game since the 1970s and finally leapfrogged its historical rival. It has all the tools to stay ahead of Intel and gain some market share from Nvidia if it blunders.

📝Investment Thesis

Well, if you understood the business and how it survived and leapfrogged competition in the last 10 years, the investment thesis would be self-explanatory.

My thesis relies on three pillars:

1) AMD Will Keep Taking Market Share From Intel

This is the obvious consequence of all the stories we have told above.

The biggest battleground here is the data center CPU market. As we have seen above, AMD is already aggressively taking market share from Intel.

Today, Intel is in no better condition than yesterday.

This is a company that:

Has no CEO.

Slow in innovation.

Grappling with manufacturing problems.

On the other hand, we have AMD that has everything Intel lacks:

Great CEO.

Rapid innovation.

Only focused on design.

It doesn’t take a genius to see that the former will lose market share to the latter.

In the last quarter, AMD brought in $3.5 billion data center revenue while Intel generated $3.3 billion. Yet, as of Q1 2024, AMD still only had near 24% unit share in the data center CPU market.

As Intel keeps wandering around like a headless chicken—it literally has no CEO— AMD will keep executing and taking market share from Intel.

2) Giants don’t want a GPU monopoly.

Nvidia dominates the GPU market, there is no question.

There is a problem though: Its customers don’t like this domination.

Don’t confuse the data center GPU market with the home computer chips market. Nvidia is not selling to the end users who don’t care how strong the company they buy from.

No. Nvidia is selling to cloud giants and they don’t like being dependent on Nvidia because this provides it with huge supplier bargaining power and major influence over other firms. Everybody sees it. People even made this into a meme:

This is why Microsoft, Amazon and Google are also developing their own chips. As they invest to come up with comparable chips, they will also likely actively discover and try alternatives to see whether they have any advantage they can derive.

After all, if everybody is waiting in the line for Nvidia Blackwell and everybody will get only 100,000 chips initially, you can gain an advantage if you can buy 300,000 AMD MI300X and use them in your data centers.

3) AMD Architecture May Have An Edge In Inference

What is AI?

Today it’s Large Language Models or LLMs.

These models are trained on general, labeled data and designed to answer as many questions as possible.

It won’t stay that way. Think about how humans have evolved.

We were also generalists. In early human cities, people who could both hunt, gather and build were valuable because these were existential skills.

Then, as our civilizations grew, we specialized because a generalist couldn’t think deep enough to build complex cities. A great architect can't become a great architect if he spends 40% of his time farming.

This will happen to AI agents too.

We will transition from large models to smaller more specialized models.

These models won’t require more extensive training but require more advanced inferencing and they’ll have to do it faster and for cheaper. Meaning, they will require more CPU involvement.

At this stage, AMD chiplet architecture may allow it to create all powerful chips with interconnected GPU and CPU cores like its MI300A. These chips could be more effective and efficient to run smaller, specialized models.

AMD’s near decade long experience in chiplet design will provide it with a significant advantage in the era of small models that will require extensive inferencing.

📊Fundamental Analysis

➡️ Business Performance

AMD’s business performance is not just good, it’s legendary…

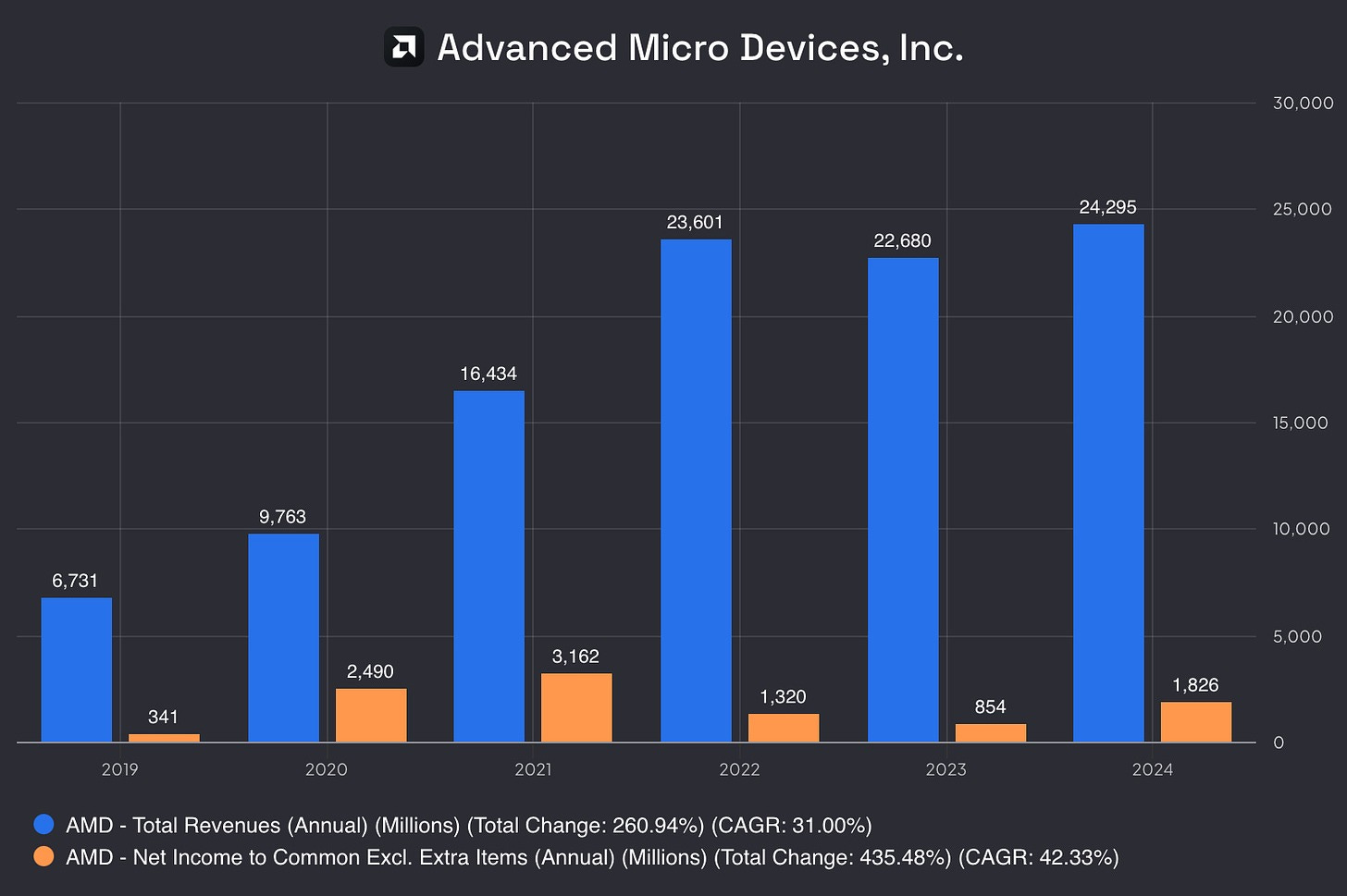

Take a look at it:

Revenue nearly quadrupled since 2019!

Remember, this is not a startup that has just found the product market fit and quickly scaling. No. This is one of the oldest chip designers in the market, founded roughly at the same time with Intel.

What does this tell you? It tells us that it’s finally leapfrogged its competition and quickly gained market share. Explosion of revenue that comes after nearly 55 years in business validates this point.

Yet, despite generating 5 times more income in 2024 than 2019, it’s generating less income than 2021. This also shows how competitive the business really is. Its revenues are exploding but it’s not able to translate a decent share of it to net income as it has to spend a lot of money to stay ahead of the competition.

Still, this is an amazing performance. It doesn’t get better for a leading chip company that’s been in business since 1969.

➡️ Financial Position

It’s as solid as a 5,000 year old fossil.

AMD has minimal debt, just $2.2 billion against $56 billion in equity and $4.4 billion of annual EBITDA.

This isn’t a picture that requires further elaboration on financial health. It’s obvious that this company will weather any storm.

No, this requires us to think bigger.

As you see shareholder equity jumped in 2022. This was due to AMD’s acquisition of Xilinx in an all-stock $49 billion deal. This was a crucial deal as Xilinx was a leading provider of chips that could be reprogrammed after manufacturing. This architecture could be especially useful in accelerating workloads like AI inference, video transcoding, and network processing.

AMD is essentially betting on future technologies while keeping its balance sheet strong. Even if you exclude goodwill and other intangible items that came with Xilinx acquisition AMD still has more equity than debt and its EBITDA can pay all the debt within a year.

This is a great picture for a leading tech company in a very competitive, R&D intensive space.

➡️ Profitability & Efficiency

Return On Invested Capital

This is probably the most important metric for all tech companies, especially the ones in competitive spaces.

In such cases where companies need to constantly invest, future returns are essentially determined by how much return they generate on their investments.

AMD is doing great here.

At the first look, you might think that its ROIC has plummeted and see this as a negative factor. However, remember it acquired Xilinx in 2022 and this skyrocketed its equity balance. This is why ROIC collapsed in 2022. Thus, it’s not indicative.

If you look before that, you see AMD is doing a phenomenal job with ROIC. Meaning, you will also likely do a phenomenal job in your investment in AMD provided that you buy it at an attractive price.

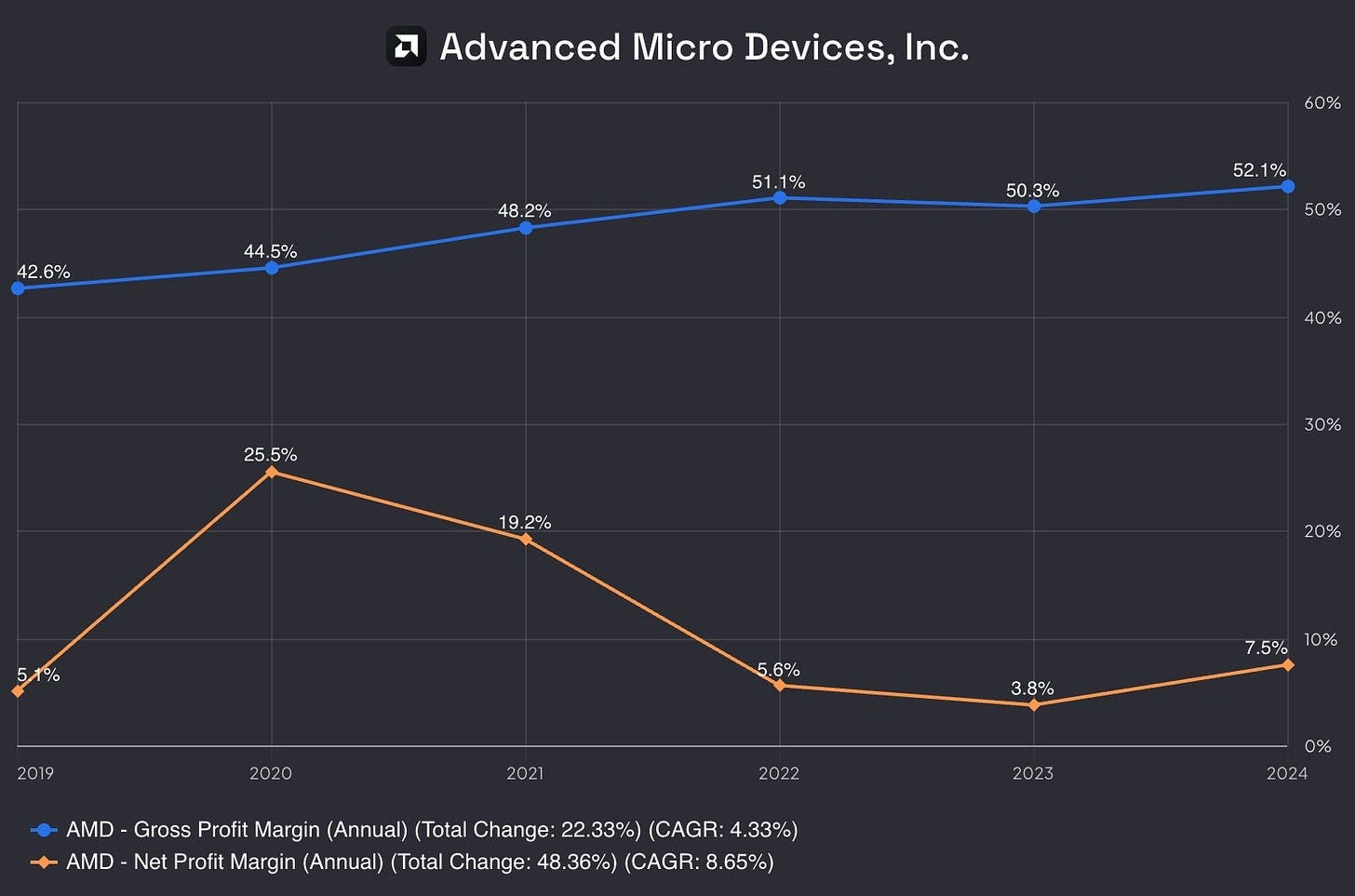

Gross & Net Margins

This is also reflective of all the comments we have made so far about the business.

As you see, gross profit margin expanded regularly in the last 5 years.

What does this mean?

Easy. It’s been competing with Intel in its largest business, data center CPUs, and expanding gross margin tells that it retains its superior position. It’s able to charge more than the competitors, validating the notion that it really has superior designs.

Yet, it’s not translating much of its gross profit to real earnings. That’s also natural.

Intel is trying to catch up and AMD itself is also playing the catch up game in the GPU front. It has to pour money in R&D in both spaces and it’s been doing just this. It’s all normal.

Overall, I think AMD is in a great competitive position as indicated by its gross margins and it’ll reap the benefits of its investments once the development in the chip space plateaus a bit.

📈Valuation

If you don’t have a company that has durable competitive advantage, valuation gets tricky.

As we have discussed, AMD is not a company that has a durable competitive advantage but it has capability to stay ahead of the curve.

This is the best you can get in high-tech markets.

This lack of durable competitive advantage is, to some extent, balanced by the fast growing markets it's operating in and its ability to compete head to head.

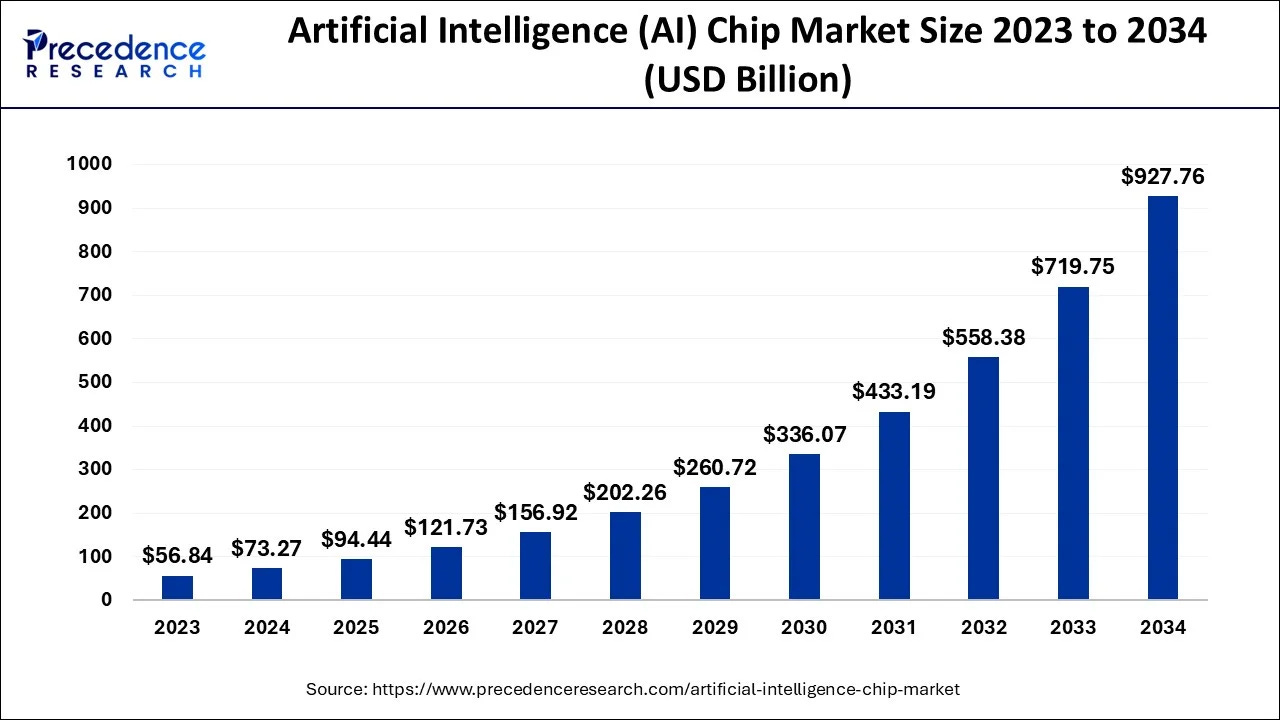

Market research firms estimate that the AI Chip Market will reach nearly $930 billion by 2034.

Data center CPU market is also estimated to double in size in the next 10 years.

In total, AMD is looking at more than a $1 trillion market opportunity if you include chips for other devices like computers, cars and consumer electronics.

This is a big enough market opportunity to sustain rapid revenue growth for competitive firms in the market even if they don’t have durable competitive advantages. Pie is large enough for everybody. All you can do is to stay competitive and we saw that AMD has capability to do this.

Given the market opportunity and AMD’s track record of 31% annual revenue growth in the last 5 years, we can conservatively assume that it’ll grow revenue 20% annually in the next 5 years.

This gives us approximately $60 billion revenue for 2030.

Nvidia has a 55% profit margin while Intel had around 25% profit margin before it got disrupted in 2022.

AMD’s revenues will predominantly come from high margin server CPU business and GPU business. It’s reasonable to expect its GPU business will never reach profitability levels like Nvidia’s. Thus, we can expect it to have an overall profit margin around 30%.

This gives us $18 billion net profit for FY 2030.

Attaching a conservative 25 PE, we have $450 billion business, 2.5 times of today’s valuation.

This may not satisfy those who expect it to make 10x in a short time, but it’s still a satisfactory return potential based on a realistic evaluation of the business, not on pure stories.

🏁Conclusion

AMD is a great company, but it’s a great company in one of the most competitive markets.

Does it have all the tools to stay ahead of its competition? Yes it does.

Is it guaranteed? Not nowhere near.

It has a great track record of staying competitively in the game and it’s also recently been winning it against Intel. It has a great CEO, flow of talent and area expertise that allows it to innovate and come to the market fast.

Yet, it’s not a 10x investment now as some people want it to be.

It had chased Intel for years and the stock exploded when it finally leapfrogged it. Now it has to chase Nvidia and we don’t know how long it’ll take or even whether it’ll ever catch up.

Still, this doesn’t mean that it can’t provide satisfactory returns.

Chip market is already big and will grow exponentially in the next decades. If it manages to stay competitive, AMD can take its fair share from this pie and provide shareholders with above market returns.

It’s a fair deal, and remember, with great companies all you can get may be a fair value, not a bargain.

The most fascinating parallel here isn't AMD vs Intel, but how AMD's chiplet architecture mirrors the broader tech industry's move toward specialized, interconnected systems. Just as the first cities weren't built as single megastructures, but as interconnected neighborhoods, the future of computing might favor AMD's modular approach over monolithic designs.

Good work, Oguz! I was planning a Quick Look post on AMD. I will link to your article so my people can read up further.