🚨Trade Alert 13: Exiting Two Positions, and Increasing One Position

Growing the cash position while also capitalizing on a no-brainer opportunity.

I’ll jump to the trades in a minute, but first, let me talk a bit about what’s happening in the market, as I see many people are trying to make sense of the downward movements in the last weeks.

I’ll start with a quote from Charlie Munger, which I think squarely fits what we are seeing in the markets currently—“Entities shouldn’t be multiplied beyond necessity.”

This was Charlie’s take on Occam’s Razor. It’s the principle suggesting that among all the possible explanations of an event, the simplest one is probably the right one.

It’s not just Charlie Munger; look at many successful people from different disciplines, and you’ll see this theme play out over and over again.

Find the simplest thing that works and do it. — Naval Ravikant

If the business is complicated, it usually means it’s broken. — Jeff Bezos

Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler. — Albert Einstein

Yet, people have an inexplicable tendency to make things complicated. I think the soccer legend Johan Cruyff explains this tendency best:

I honestly think that the same applies to investing with all its force. Investing is simple, but keeping it simple is extremely hard. This is what I have been observing in the recent weeks: people are making it more and more complicated, especially as the market pulls back from all-time highs.

I see many reasons being thrown out to explain the recent pullback:

Concerns about the scale of AI investments.

Skepticism about the continuing rate cuts.

Increasing default rates of consumers.

There are millions of other reasons people are throwing out every second. Just browse on Twitter or watch CNBC for 10 minutes, and you’ll see many of them.

I think it’s a vain effort to try explaining the market dynamics.

If it weren’t, we would have at least one person who cracked the whole mechanism, and he would become the richest person on the planet with ease; instead, the ranks of the richest are dominated by entrepreneurs, not by market makers.

The market is a complex mechanism that’s impossible to explain with precision. This complexity is essential as it democratizes the markets. It’s so complicated to be understood with precision by anybody, even machines, so that even the largest and most sophisticated actors can go bust as a result of uncertainty, like Lehman Brothers.

Complex systems like the markets are impossible to control and maintain. Nassim Taleb explains this well in Black Swan:

“Complications lead to multiplicative chains of unanticipated consequences, followed by apologies about the “unforeseen” aspect of the consequences, then another intervention to correct the secondary effects, leading to an explosive series of branching “unforeseen” responses, each one worse than the preceding one.”

—Nassim Taleb in Black Swan

When we interact with complexity, instead of predicting the interaction among the variables and possible outcomes, we should maneuver around them by anchoring ourselves to the simplest indicator available.

Businesses, as microeconomic units, have sold this long ago. Instead of tracking thousands of different variables that could affect the business performance, they track a small set of variables that are called key performance indicators.

Take a coffee shop business as an example. There are too many variables like consumer sentiment, weather, commodity prices, inflation, GDP growth, etc.. All these variables affect each other in a complex system. If the day starts rainy, the traffic will likely be less than usual, but if the rain starts unexpectedly during the day, the traffic may spike instantly as people would want to have a cup of coffee while waiting for the rain to stop.

If the business tries to track all these variables, it’ll be lost in complexity. Instead, it tracks one simple indicator called same-store-sales, looks at the long-term trend to smooth out temporary effects, and measures how its actions affect the long-term trend.

When we try to navigate complexity through complexity, we lose. This is also why experts who operate with complex parameters, more data, formulas, and models might seem impressive but are rarely able to predict where complex systems will go because their tools increase confidence, not their ability to predict. This is why the Fed can’t know for sure where the economy will be a year from now despite all the data, tools, and brain power at its disposal.

When it comes to markets, that anchor is the valuation.

As opposed to all those sophisticated, try-hard explanations we have seen as the cause of the market pullback, I advance valuation as the main reason.

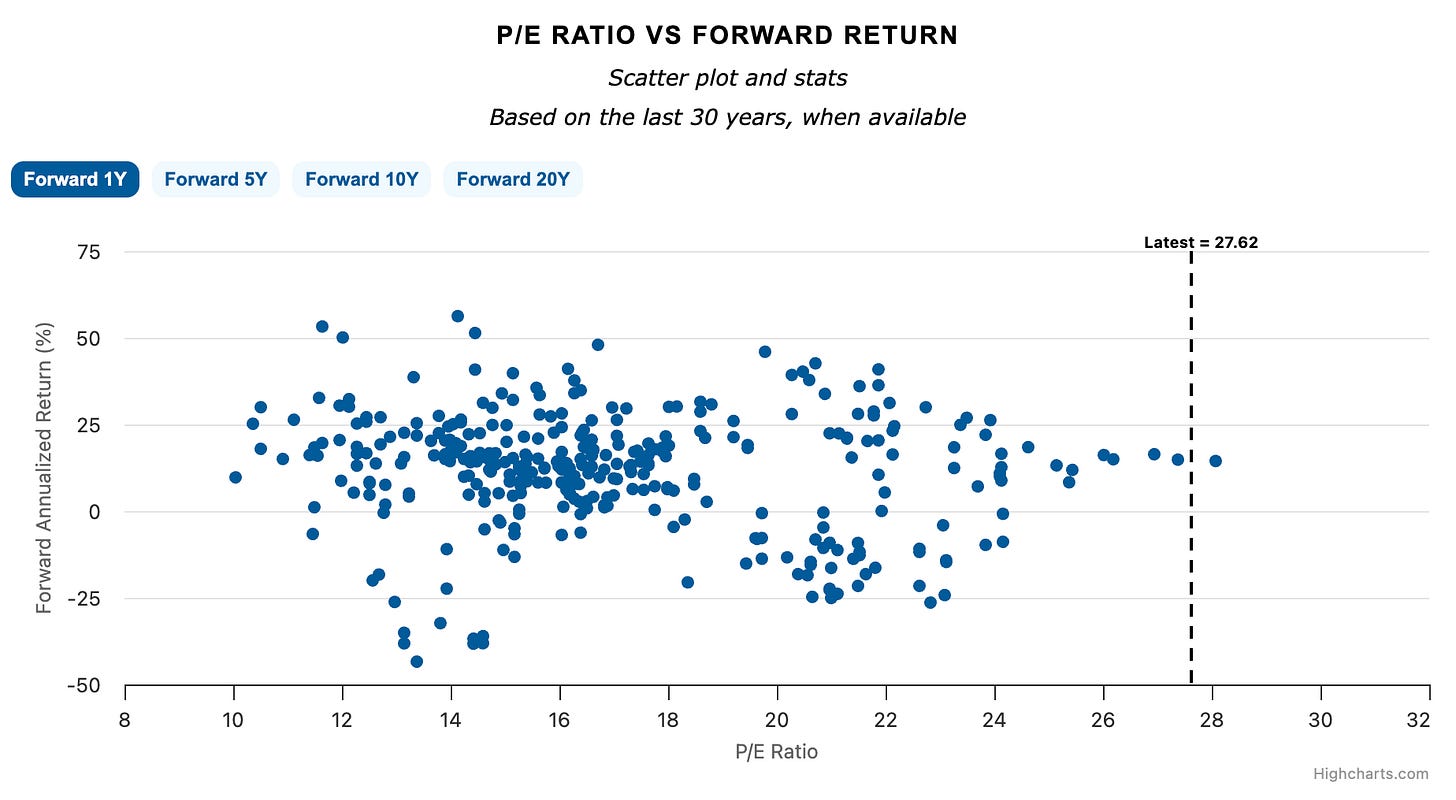

Take a look at this:

The benchmark S&P 500 is now valued at 27x times earnings on an absolute basis, and this is the highest P/E ratio it has ever reached in the last century. It didn’t even reach this level back in the days of the dotcom bubble.

As you can see, whenever the valuations reached this level, they came down drastically in the following few years. You’ll find many people who will list dozens of reasons why the valuations today aren’t worrying; however, regardless of what technological transformation we have gone through or what amazing companies were created in the process, valuations have always come down from the current levels.

I assure you that the internet was as big a technological transformation as AI. In my opinion, it was even bigger than AI, as it’s the very thing that allows the diffusion of AI technology today. Yet, valuations came down regardless of the internet’s effect on the world and the greatness of companies created on it, like Facebook and Amazon.

So, the market is already overvalued on historical measures; this is clear, and it already puts downward pressure on the prices.

How all the variables like consumer sentiment, GDP growth, inflation, etc, and thousands of other factors are interacting, driving investors to yield to that pressure, is immaterial. It’s immaterial because the interaction of these factors is indecisive, while the downward pressure created by high valuations is decisive.

What I mean is that the interaction between these factors changes day by day. For some periods, it could produce a positive sentiment that resists the natural downward pressure created by high valuations. In such a case, valuations can even go higher. However, that interaction eventually produces a negative sentiment, and when that happens, buyers quickly turn to sellers as downward pressure is still there. Because it’s decisive, it eventually wins. Vice versa is also valid when the valuations are unduly depressed.

We can easily see this effect below.

If we look at 1-year forward returns when the S&P 500 trades above 22x earnings, we can see a wide range of outcomes:

We can see that, for some reason or another, high valuations can sometimes be sustained, and the next year could produce returns as high as 50%, while low valuations can produce returns as low as -45%.

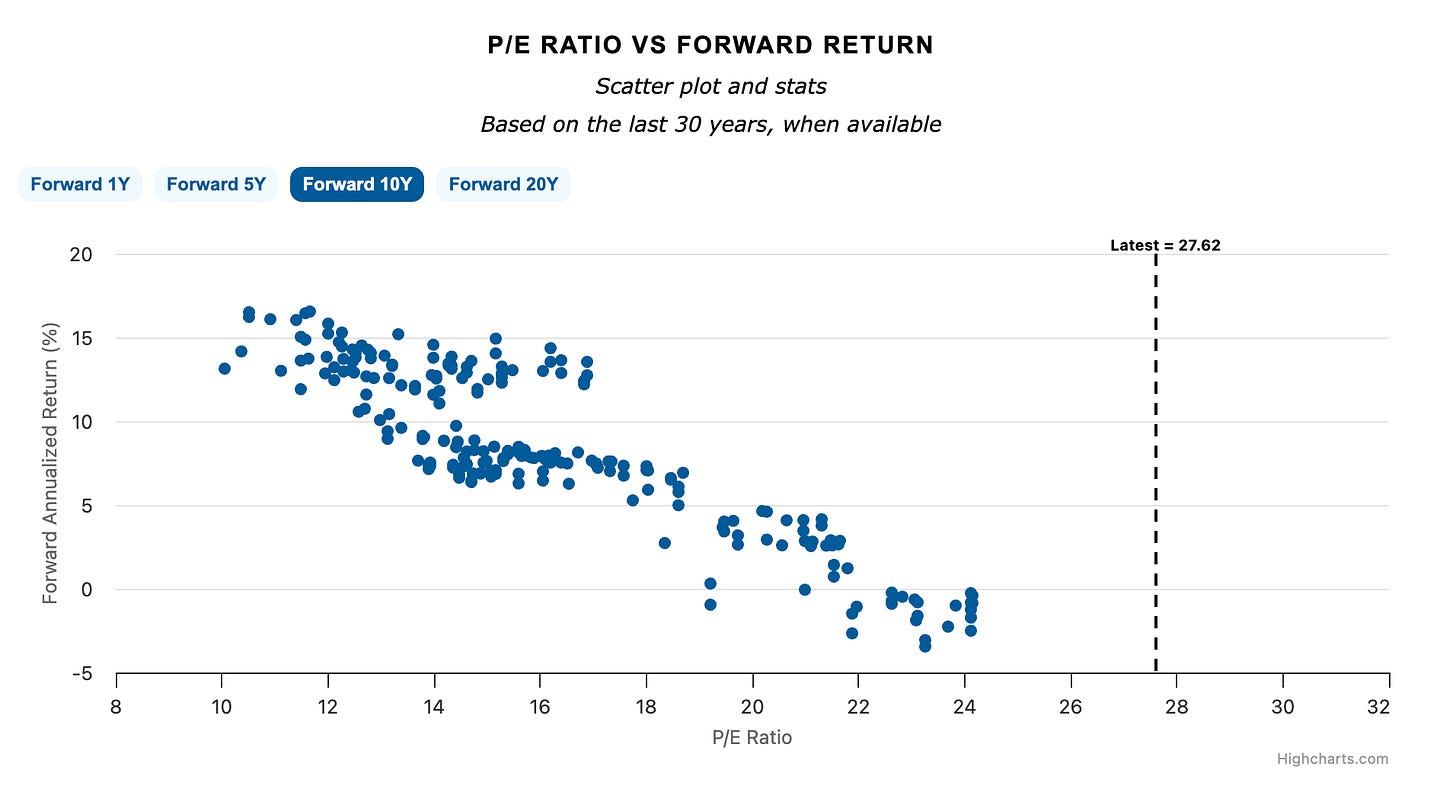

However, when we look at 10-year forward returns, the picture changes:

When the market is valued above 22x earnings, annualized returns for the next 10 years have always been negative, while valuations below 18x earnings have always produced positive returns.

This clearly illustrates that the interaction of economic variables can breed any result in the short term, as they are indecisive; however, valuations always dictate the long-term direction, as mean reversion is a force of nature, and it’s decisive.

Thus, it’s a vain effort trying to predict what the variables are at play now and how they are interacting to produce the pullback we are currently seeing. One true reason for what we are seeing now is simply the sky-high valuations.

Don’t listen to those who are posing like they are making sense of the pullback. If they could do that, they should have done it before the pullback, and we would see. Cheap talk isn’t worth a dime in the market.

We have been warning about these valuations for a while.

As our community would know, the last time I injected fresh capital into the market was in March, and I have been circulating the money between exits and new positions since then. I haven’t opened a position more than 1% big lately, and have been recommending everybody to avoid injecting a lot of capital into the market at the current valuations.

In fact, we did more than just stop to inject fresh capital in the last three months. We have completely repositioned the portfolio for sustained outperformance.

As you know, our portfolio has been performing at the elite level since inception:

2023: 36%

2024: 50%

2025 YTD: 41%

As a result of this, many of our positions had become overvalued, and the only way for them to go higher was through further multiple expansion. This wasn’t likely, as most of them were already trading at elevated P/Es. These positions were increasing our downside risk without promising further upside.

We cut some of these positions and completely exited some of them, like Hims & Hers when they were elevated and rolled to the proceeds to new opportunities that structurally have lower downside risk than the upside potential.

In the last two weeks, I have turned even more defensive and exited six positions. A large portion of the proceeds went to our cash pile, while a smaller portion funded the undervalued opportunities we have spotted in the last two months.

These efforts have produced two results:

Larger cash position.

The volatile, aggressive growth side of our portfolio is now made up of positions that are closer to their bottom than the positions we had before, which limits the downside risk.

Today’s transactions will maintain these efforts by:

Exiting two positions.

Increasing one position.

This way, we’ll again raise substantial cash and fund a growth position that is trading at dirt-cheap valuations.

You’ll also find the new link to the portfolio spreadsheet with updated valuations and recommendations at the end of the write-up.

Let’s get started.

Here are the exact trades I am making:

Let’s start with the exits.