🚨Trade Alert #10: Opening A New Position and Increasing Three Positions

Adding a new growth position, and increasing positions that are attractive in terms of risk/reward in an all-time high market.

“The market valuation is worrisome.”

I am not saying this; it’s Howard Marks, and when Howard Marks says something, we pay attention.

He dropped a new memo last week titled “The Calculus of Value.”

He makes a simple observation:

The market valuation was already stretched at the end of last year.

Macroeconomic and business conditions haven’t gotten better.

Yet, the market multiple has increased rather than decreased.

Indeed, most people agreed at the end of last year that the valuation was a stretch, but we weren’t in a bubble.

I have also said that many times.

I thought the reason was simple—the domination of tech companies, especially Big Tech.

What does it mean?

Well, P/E ratio isn’t alone sufficient to value stocks but it has historically been a fairly accurate yardstick to measure the market valuation.

The average P/E of the S&P 500 in the last century was 18.

Meaning, everything above it could be thought of as overvalued, while everything below it could be thought of as undervalued.

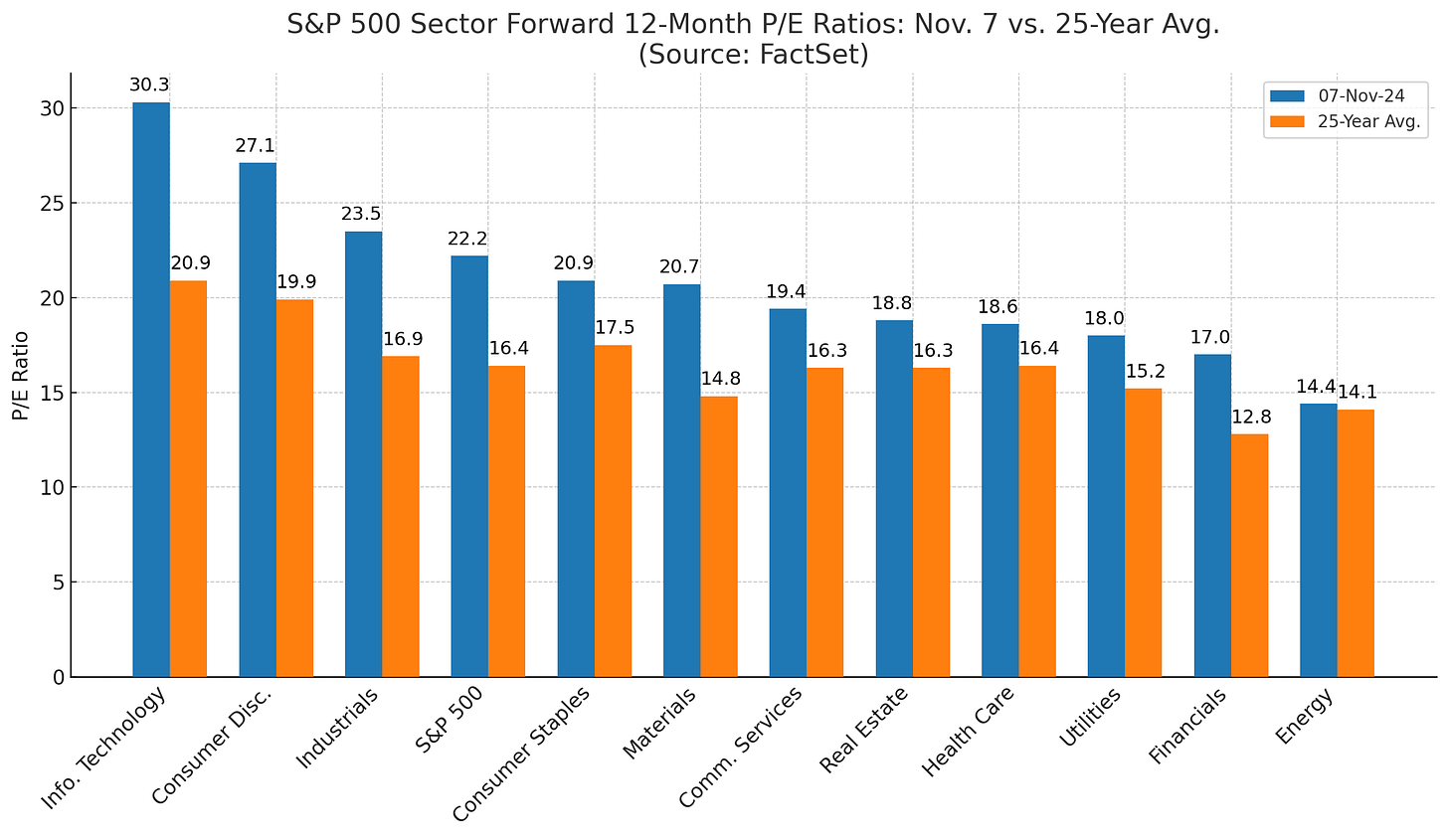

At the end of the last year, all S&P 500 sectors were ahead of their 25-year average. Not a single one was behind:

This was obviously expensive, but I have said again and again that it was nowhere near a bubble, and 22 P/E was actually less expensive now than it would have been in 1990.

Why? It’s simple.

In the 20th century, the market was dominated by industrials. The biggest investment of those companies was plant, property, and machinery. All of these items are tangible investments with more than a year of useful life. Thus, these companies were capitalizing their investments so they didn’t eat away their earnings.

This has changed in the last 20 years.

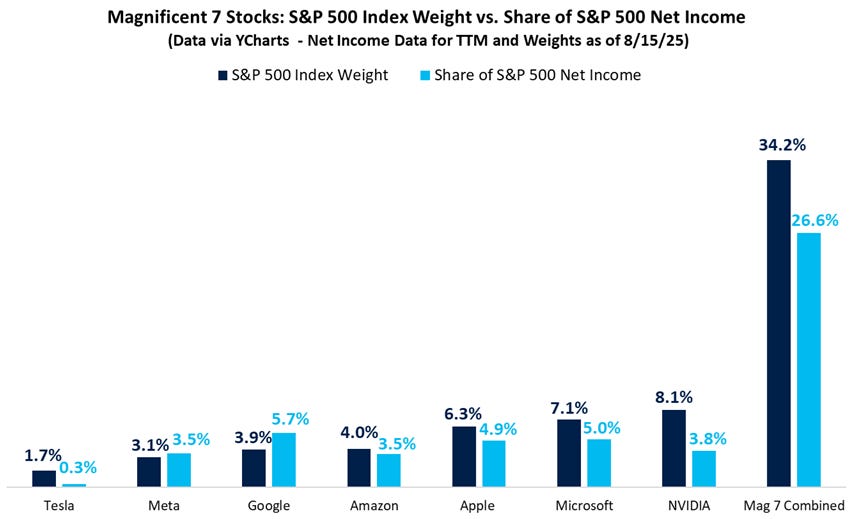

Currently, large-cap tech companies, or so-called Mag7, have a combined weight of 34% in the index. Among the remaining 493 companies, there are way more tech companies than there were 20 years ago.

The fundamental difference of tech companies is that most of their investment is intangible, things like talent acquisition, investment in human capital, processes, etc.

Accounting Professors from Columbia Business School estimate that 90% of the R&D spending and as much as 80% of SG&A expense could be classified as intangible investment for companies in technology sectors. (Click here if you are interested)

Yet, intangible investments aren’t capitalized because they don’t have something like useful life. Thus, they are expensed in the income statement. This artificially reduces income and balloons the P/E ratios.

Thus, I think 23-24 times earnings for tech companies would have been similar to 20 times earnings for industrials. Expensive indeed, but nowhere near a bubble.

This is why I insisted that the market seemed a bit stretched but nowhere near a bubble at the end of last year.

We kept selectively adding on to our positions, bought new ones, and exited the positions that we thought had become too risky.

That worked incredibly so far. Our portfolio outperformed the S&P 500 by over 30%, delivering over 45% return in the last twelve months.

Yet, as the market appreciated, the calculus of risk has also changed.

Today, the average P/E of the market is around 27, yet we have:

tariffs,

ticking up inflation,

slowing global trade,

credit spread near all-time lows.

As Howard Marks observes, business conditions deteriorated, but the valuations have gone up as if the outlook is better.

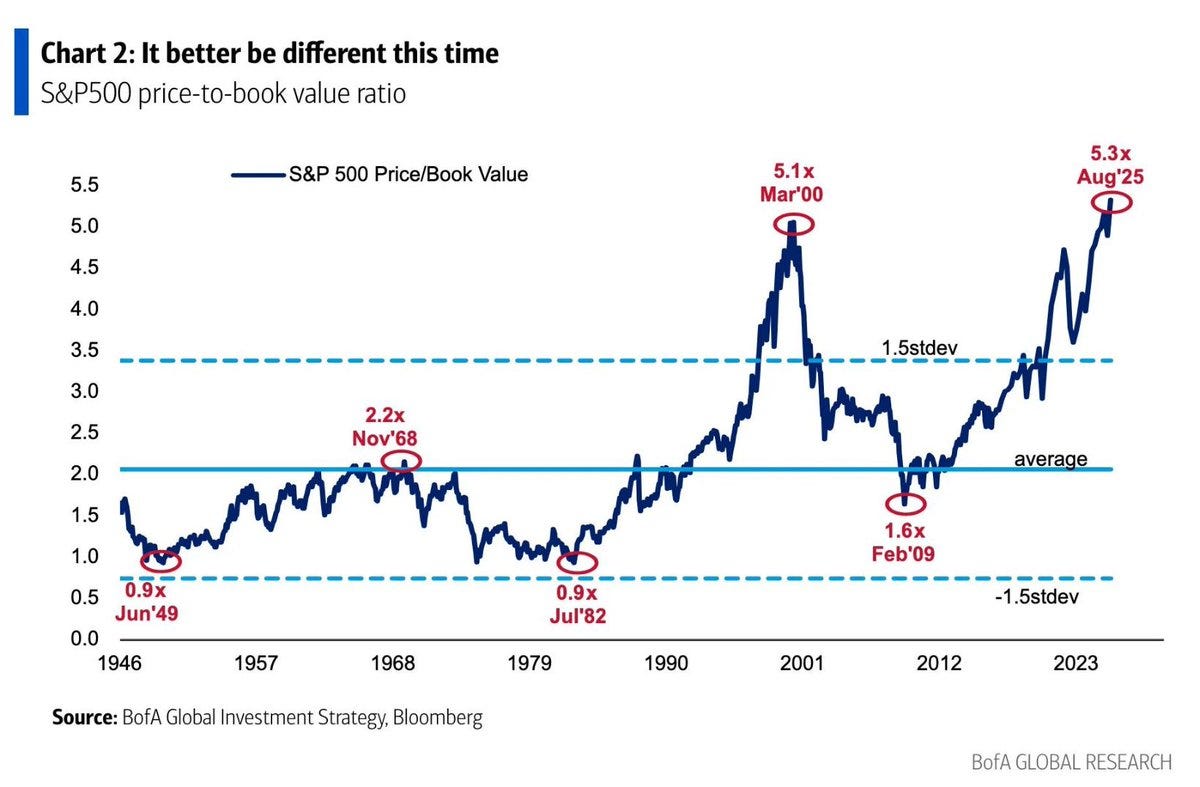

The market today is valued at around 5.3 times book value.

Buying the S&P 500 at this point resulted in 3% annual return for the next 10 years last time it happened:

Again, we can make the same argument that 5 times book value isn’t nearly as bubbly as it was in 2000, because the tech companies are dominating the index now.

Yet, even if we assume the current 5 times book is actually like 3 times in 2000, it’s still very expensive historically.

Still, most investors don’t find this worrisome because they believe that this high valuation is due to the high valuation of the big tech companies dominating the index, and their premiums are deserved.

It’s true. The companies that have high weight in the index are truly one of a kind. At no time in history, a few companies dominated the global business landscape as they do now.

Today, their average P/E ratio is 33 (excluding Tesla).

It’s reasonable to assume that this would reduce to around 27-28 if their intangible investments were capitalized. For their dominance, 27-28 times earnings wouldn’t be outrageous, though not cheap either.

However, the rest of the index is still trading at 22 times earnings, and this is not cheap given that this was just around 22, including the Mag7 at the end of last year.

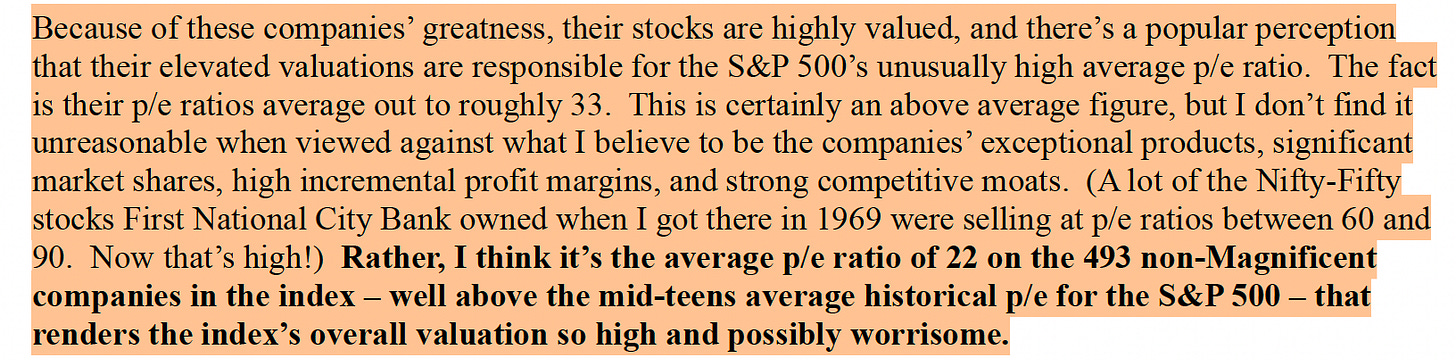

Howard Marks also acknowledges this.

He says 33 times earnings of the Mag7 is probably less problematic than the 22 P/E for the remaining 493 stocks:

I think the investor psychology proves this.

We got a 2% (yes, just 2%) pullback this week, but people are acting like we are in the middle of a crash. Some people have already started to say, “Be fearful when others are greedy.”

Let me be straight—this is nothing.

The market isn’t crashing, there aren’t huge, obvious dips to buy, and valuations are as elevated as they were last week.

But people are acting like it’s something.

Why? Because they are afraid.

Most investors now intuitively know that the market is pretty stretched, yet most of them couldn’t keep from making bets because of FOMO. Their averages are now so high, and even 2% pullback makes them feel like the crash is coming.

So, the question is simple—what should we do now?

Should we just switch to cash, exit markets?

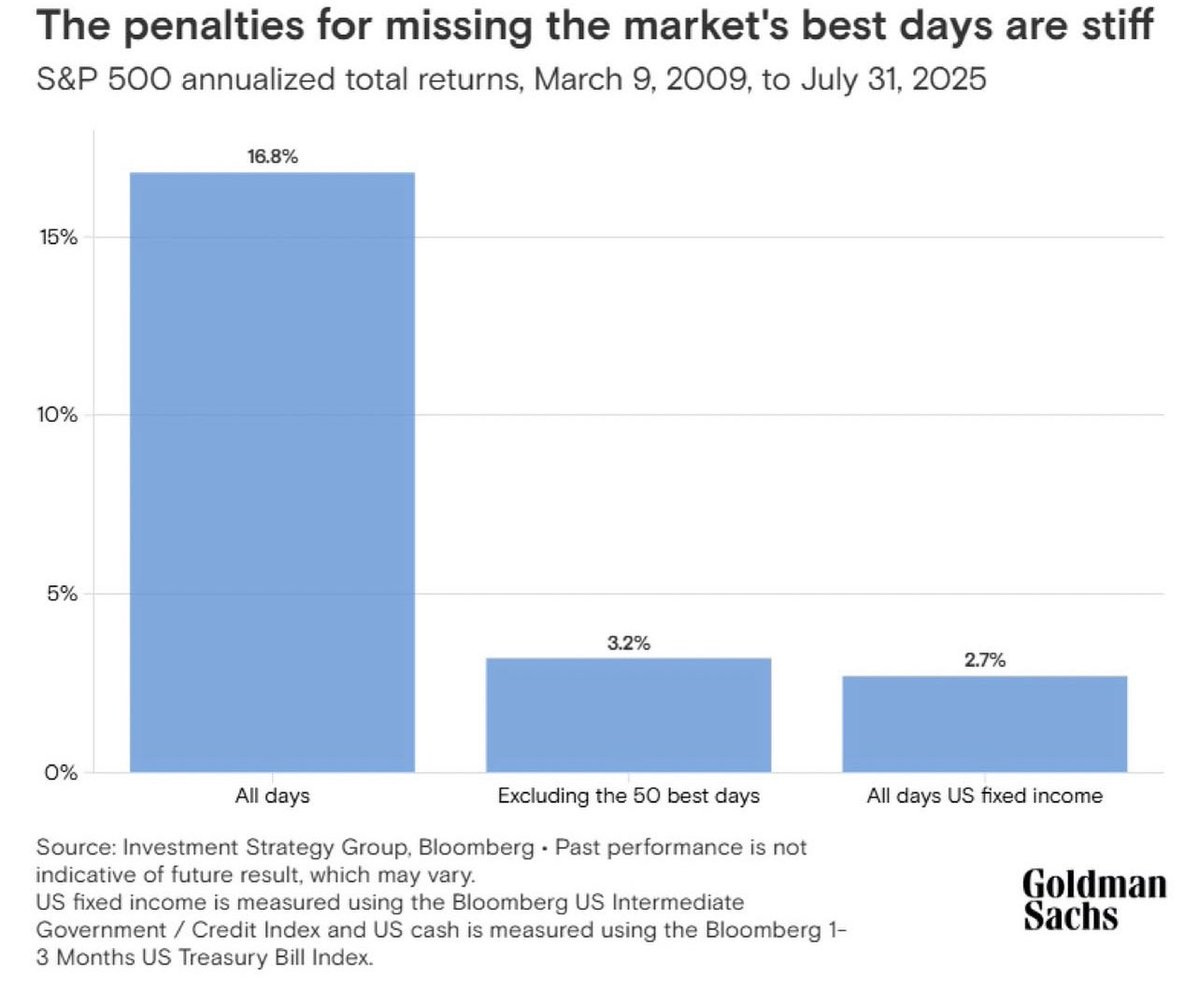

I don’t think so. I think exiting the market is perhaps equally risky as buying at elevated valuations. If you buy at elevated valuations, there is at least a chance that the valuation may be justified in the future if the business is a high-quality one. But if you miss the best days in the market, you miss most of the returns, and there is no way back:

If you missed the 50 best days in the market in the last 16 years, your average annual return would have been 3.2% instead of 16.8%.

You can never know when these best days will happen. So, exiting the market isn’t an option. Should never be.

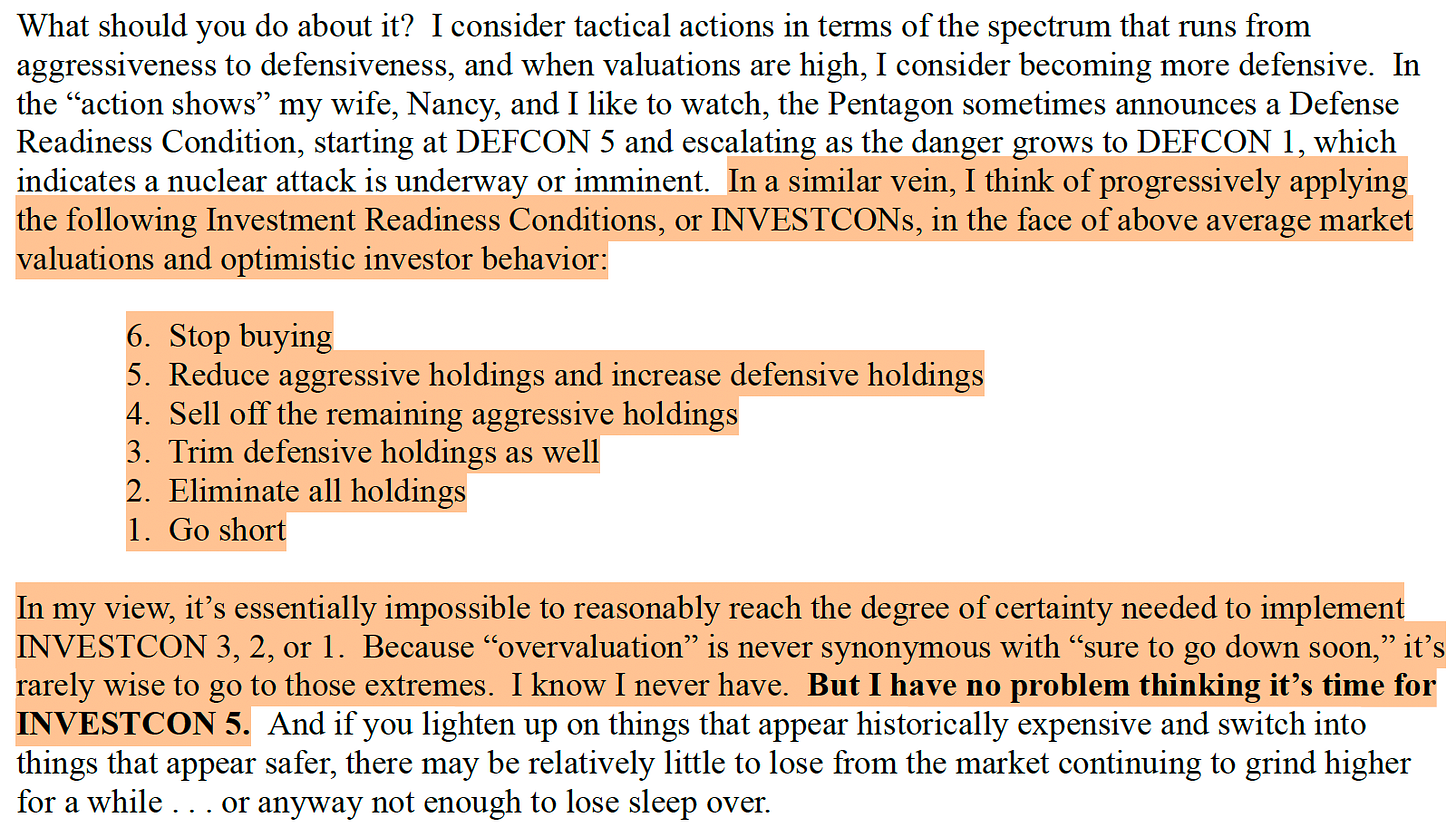

Howard Marks also acknowledges this, and he suggests 6 steps, of which only 3 are really operational:

He says he has never done the last three steps in his career. Given that he saw a few of the biggest crashes in history, I don’t think there is any reason for anybody to think that they may do the last three.

So, there are actually three steps:

Stop buying.

Reduce aggressive holdings and increase defensive holdings.

Sell the remaining aggressive holdings.

He says he thinks we are at the second step.

I agree.

If you have been following this publication since the beginning of this year, you would have noticed that we haven’t injected fresh capital into our brokerage account since we bought the dip in April.

We have still opened several new positions since then, but most of these trades were internal capital allocations. New positions were funded by proceeds from the exits. And most of the time, these operations were to derisk the portfolio. We exited the higher-risk positions and put money in lower-risk positions. As the new positions also appreciated in price, the portfolio kept growing despite becoming less risky.

So, in a sense, we have been at the second step since early May.

We’ll keep pursuing this strategy with today’s trades too.

We exited Hims and Hers last week at around $50 per share, more than tripling our initial investment in just 18 months. We reallocated a portion of the proceeds last week, and we’ll allocate the remaining portion today.

We’ll be buying positions that’ll derisk the portfolio.

This doesn’t necessarily mean we’ll only buy stocks in defensive industries.

We will also be buying:

Stocks that are derisked valuation-wise despite high growth potential.

Non-US businesses, which will cut our exposure to the systematic risk in the US.

This way, we will be positioning the portfolio more defensively, yet still maximize the risk-adjusted returns.

I think this should be the strategy for any sane investor going forward as long as the current market and economic conditions persist.

Here are the exact transactions I am making:

1️⃣ Buying Inter & Co

Inter is a Brazilian neo-bank, the second largest after NuBank and they are growing fast.

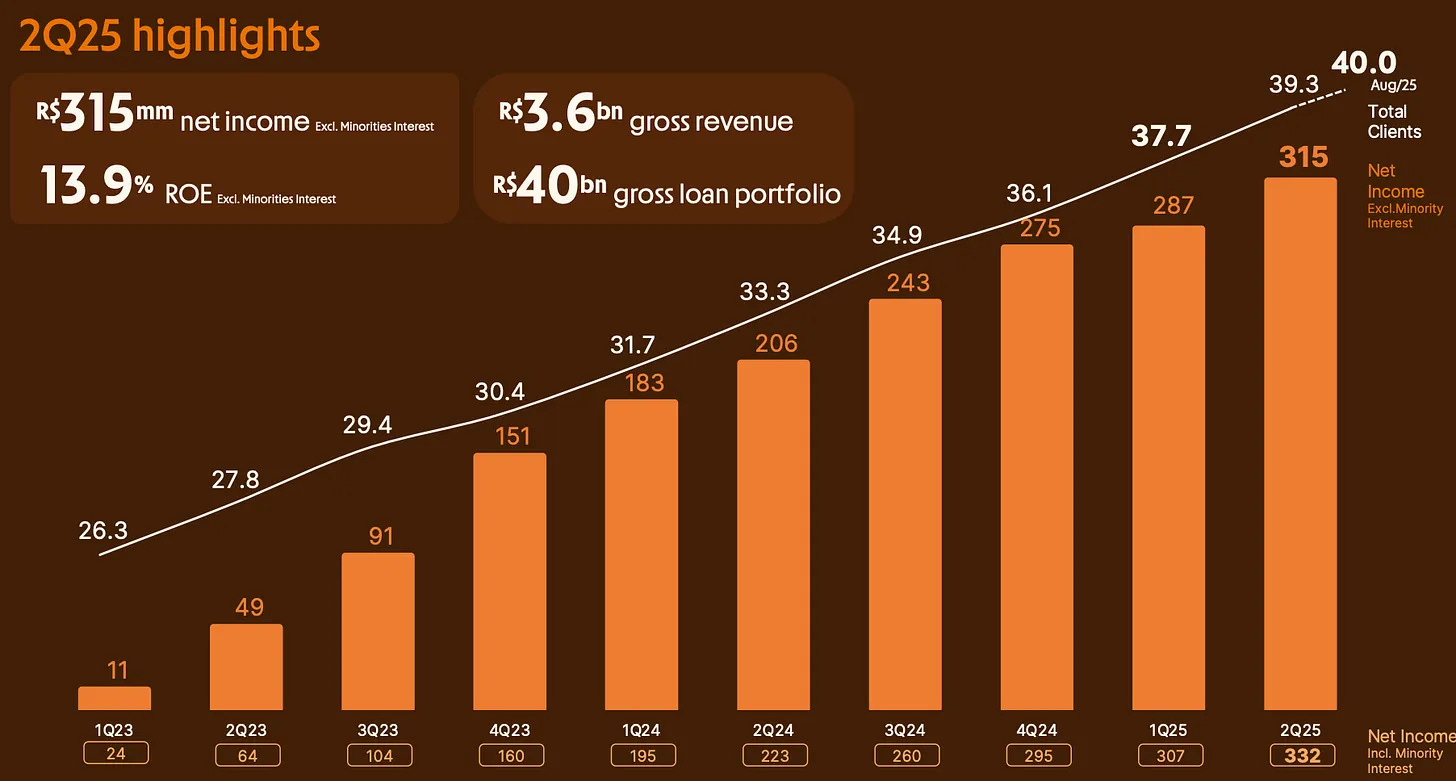

They have grown revenues 30% at an annualized rate since 2023, while quarterly net income grew 30x in the same period:

In the same period, their loan portfolio grew from R$25 billion to R$40 billion.

What impresses me is that, generally speaking, once you spot a fintech whose growth is being fueled by credit expansion, you expect two things:

Funding cost to go up.

Non-performing loan (NPL) ratio to go up.

This is intuitive as they generally ease their lending conditions to attract more customers which naturally drives their own barrowing cost.

For Inter, exact opposite happened.

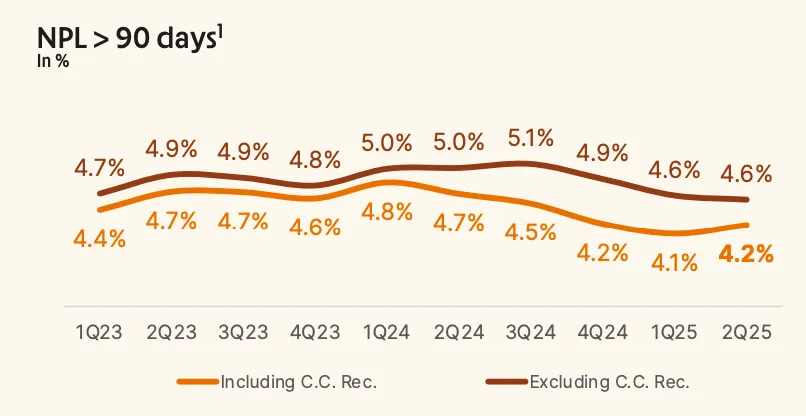

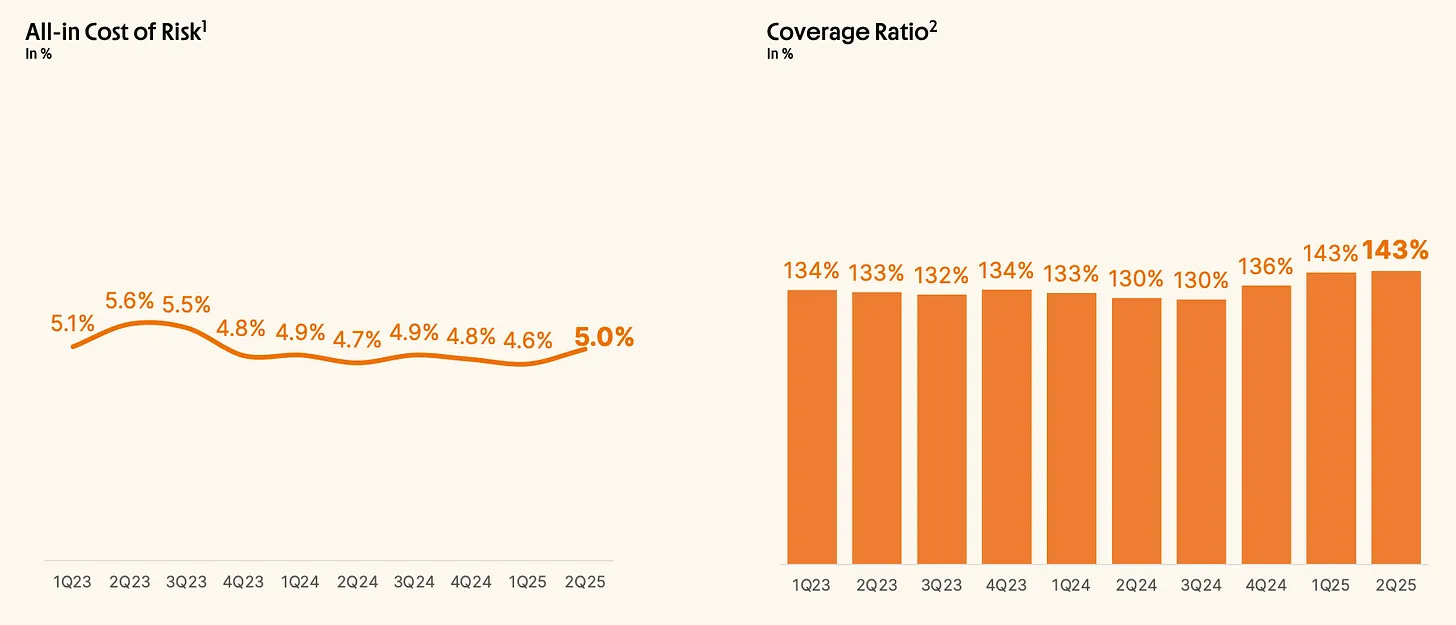

Their NPL has remained stable and even slightly gone down in the last two years:

This means that they kept their underwriting standards pretty tight in all this fast growth period. For reference, NuBank’s NPL ratio is well above 6% becasue they haven’t been that selective in their underwriting, especially when it comes to credit cards.

This naturally meant that Inter’s clients held deposits ready in their transactional accounts to service debt, meaning Inter had a plenty of “lazy money” waiting in deposit accounts that it could use to fund loans.

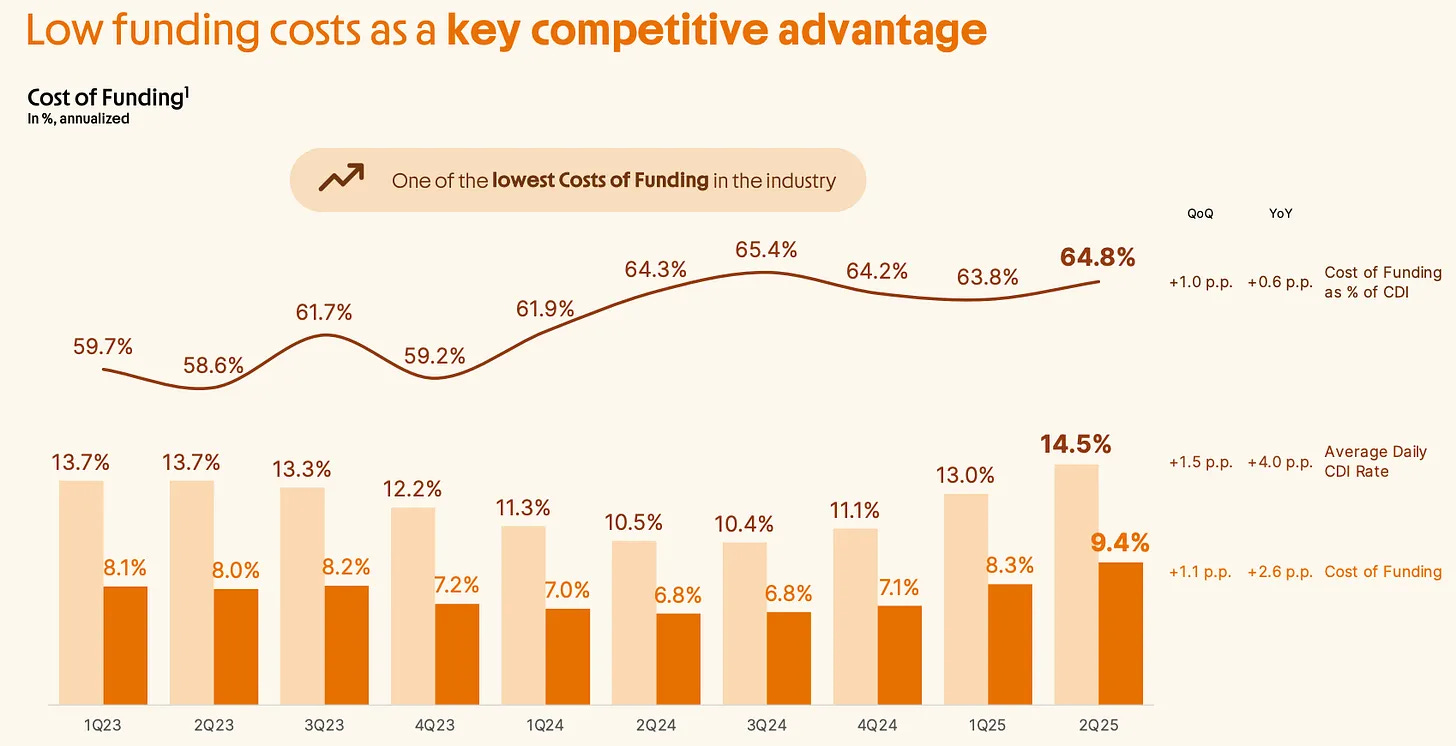

This led to a lower cost of funding than competitors:

For comparison, NuBank’s cost of funding is currently around 90%.

In sum, Inter has been growing substantially without assuming much higher risk than the competitors. I think this growth can sustain in the coming period primarily for two reasons:

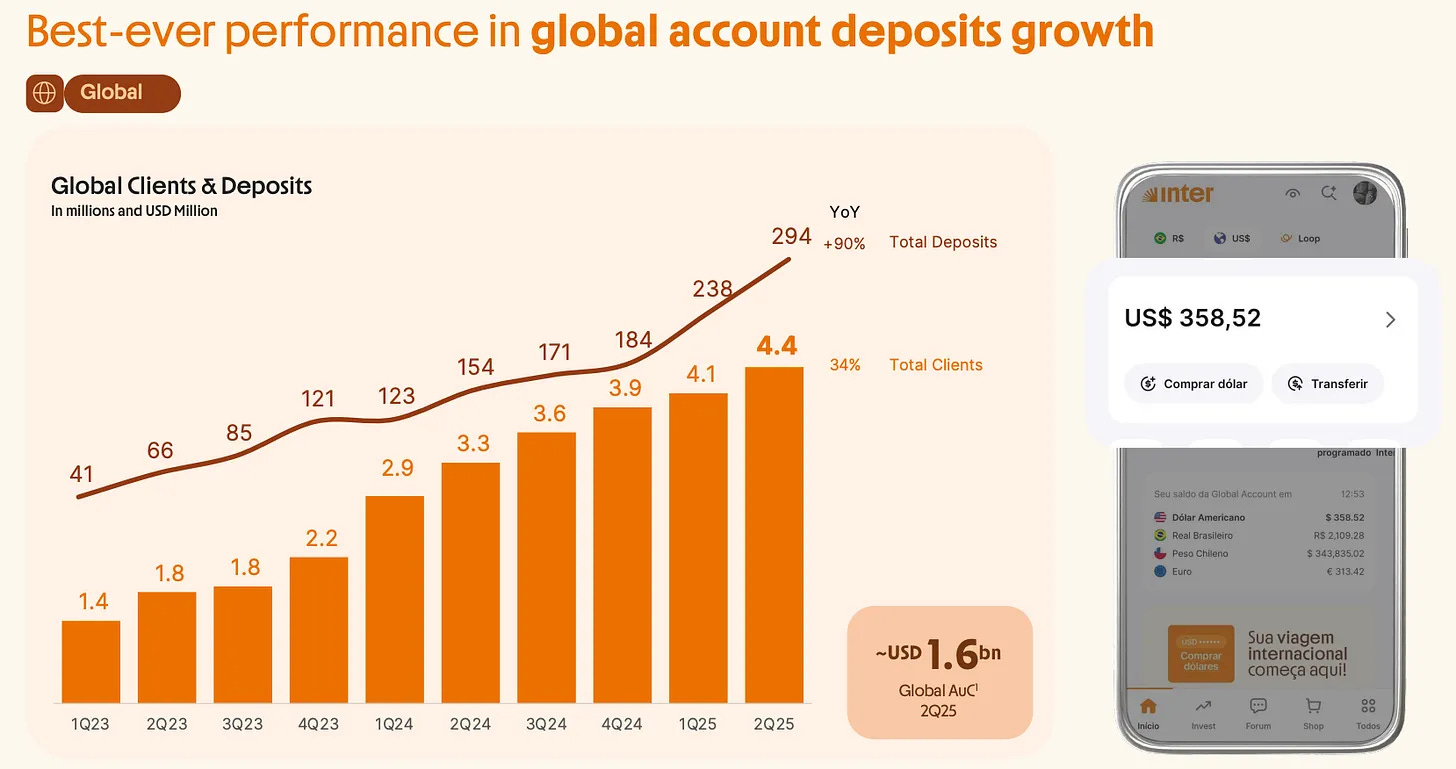

First is that they have started their international expansion.

Inter had launched global accounts in the US back in 2021 and they have reached over 4 million customers since then:

They have targeted primarily the Brazilian diaspora in the southern states, especially Florida, and that worked out pretty well.

Now, they are looking to expand in the US and they are also expanding in Latin America. They lanched global accounts in Argentina last quarter. I think this is an amazing opportunity for them as Argentina has a robust fiscal discipline under Javier Milei and unbanked population is still abvoe 25%. Plus, NuBank isn’t yet active in the country giving Inter a chance to expand without facing much competition.

There is substantial opportunity for growth both in the US and in the Latin America as the latter still has an unbanked population of over 120 million.

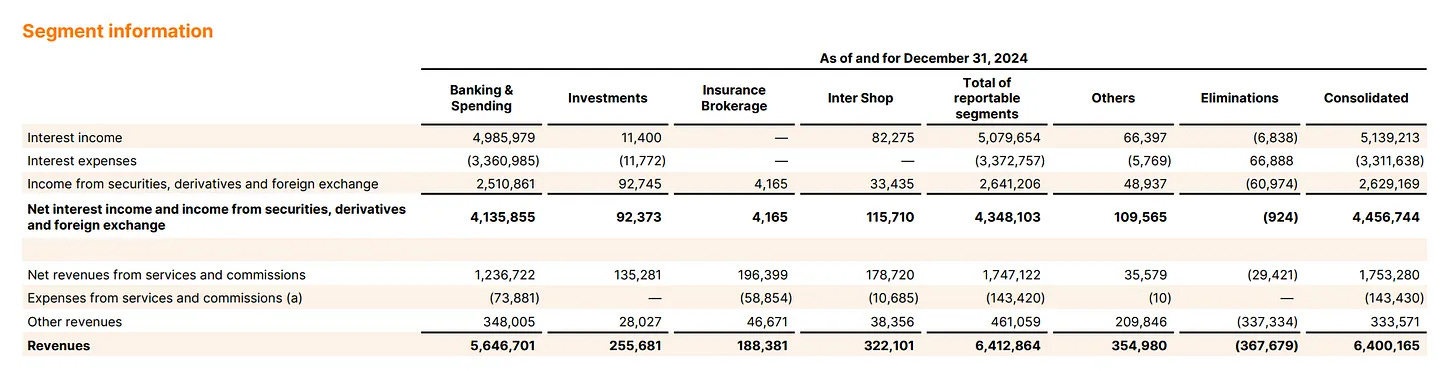

Second is that Inter has significant cross selling opportunities.

They have turned their app into a “financial super app” offering investment, insurance and shopping all in one place.

These complementary offerings now make up 13% of the total revenue:

This significant for what’s essentially a bank.

As Inter grew its customer base, it’ll be able to more aggressively tap into these segments. This will result in higher fee based revenue coming from complementors, driving both margins and the multiples up.

Overall, Inter’s future looks bright to me.

Yet, the market is valuing at just 8 times 2027 earnings. How come?

Well, I call it the “Sofi sendrome.”

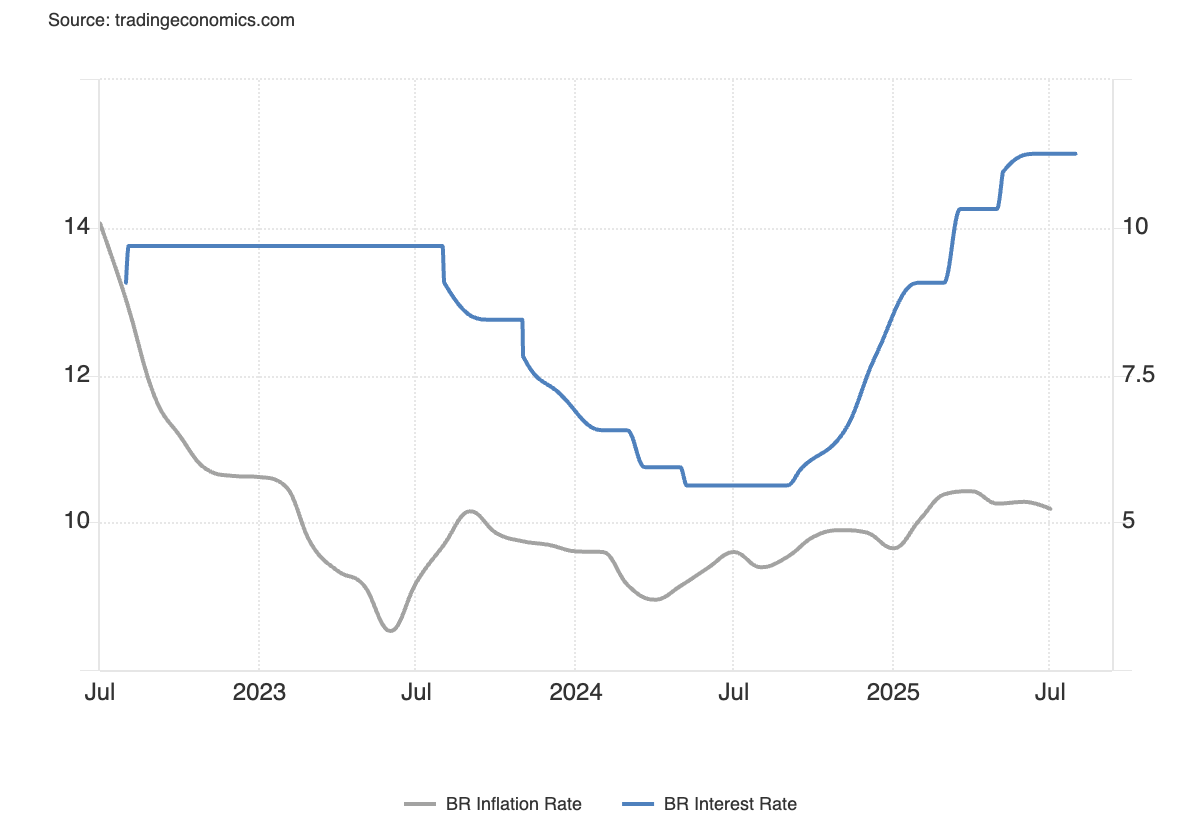

After the Brazilian Central Bank started cutting interest rates in July last year, inflation spiked from 3.6% levels to 5%, prompting the Central Bank to hike the rates again.

The market is now afraid that the NPL rate will skyrocket due to the loans made with inerest rate expectation in the prior period, eating away Inter’s earnings. This is similar to the setup that Sofi faced back in 2023.

However, similar to Sofi, Inter has managed its balance sheet pretty conservatively.

Its coverage ratio is currently above 143%, meaning loan losses can grow by 43% before starting to eat away its earnings.

Historically, Inter’s NPL ratio has never gone above 5.5% since it became public so I think it’s very unlikely that we’ll see this scenario materialize.

In any other scenario, 8x 2027 earnings is a big bargain for this company in the long term.

Valuation clearly shows this.

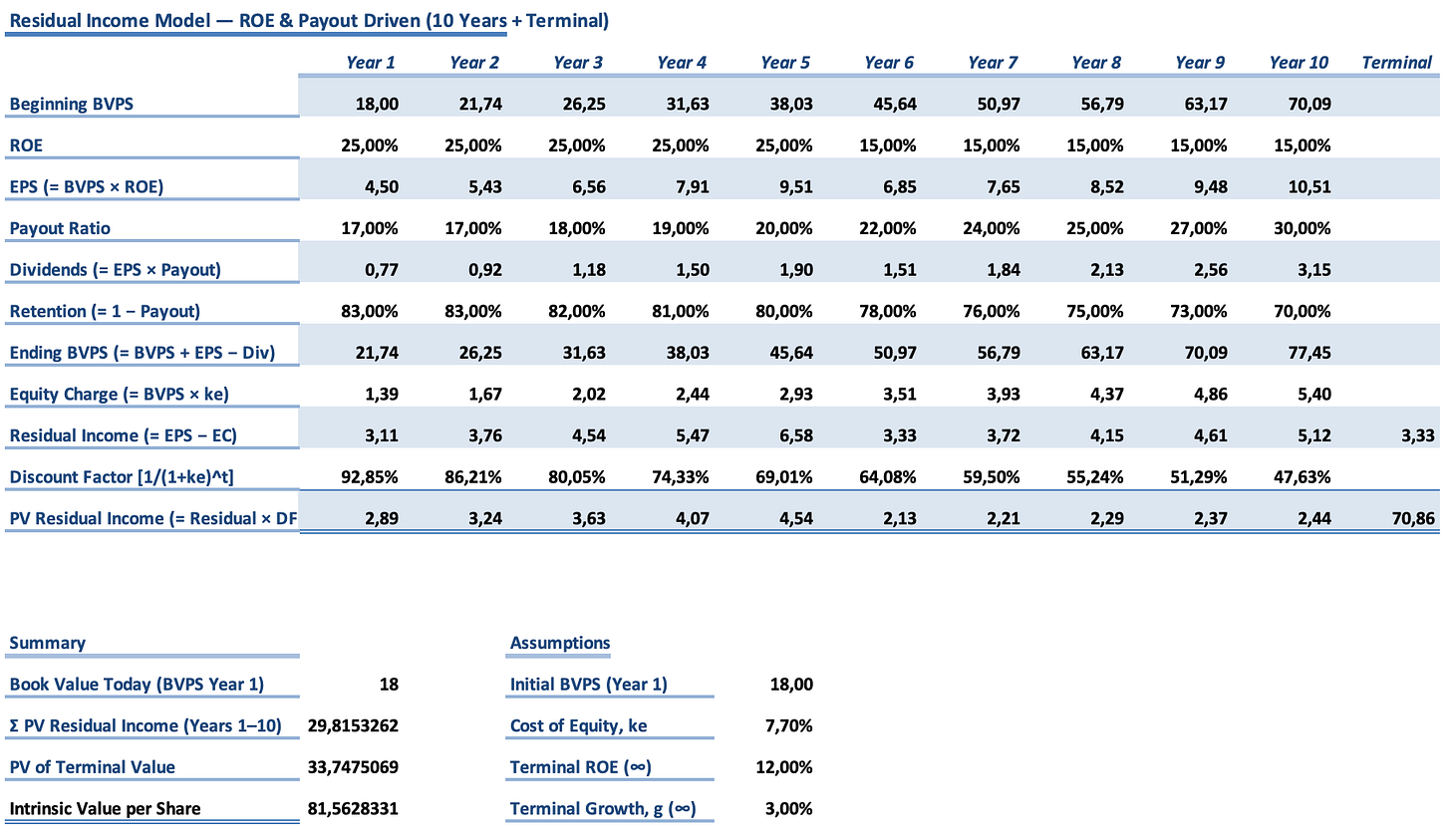

Based on a Residual Income Model (RIM) assuming 25% Return on Equity in the first 5 years and 15% beyond that with just 12% ROE in the terminal period, we get an intrinsic value way above today’s valuation:

The model gives us R$81 intrinsic value which is around $15. The stock is trading at $7.7 today.

I’ll be opening a small position today, approximately 1% of the portfolio and will buy more if it goes down, stop if it goes up.

Inter trade provides us two things:

Growth at higher risk premium than the broader market offers.

Diversification away from the US companies.

The next trades will further derisk the portfolio while maximizing the opportunities for further capital appreciation.