Software Armageddon: Opportunity Or Trap?

Software is getting disrupted or it's presenting a generational buying opportunity. Which one is true?

In 2011, Marc Andreessen, the founder of Netscape and the influential venture capital firm Andreessen & Horowitz, wrote an essay for WSJ: “Software is eating the world.”

It has become something like a motto among tech entrepreneurs as we watch everything turning into a software-based digital product.

Software made billionaires, software created jobs, software allowed people to chase their dreams, etc.

It literally disrupted many traditional business models like banking, insurance, and even matchmaking. We have literally gone through one of the biggest waves of disruption in human history.

Though younger generations heavily benefited from this disruption, many legacy businesses had to close down, and software meant losing jobs for them rather than an easier and faster way of doing things.

Fast forward 15 years, and the headlines have changed. Preadator is now a prey:

As AI models remove the barriers to creating software, worries about the disruption of software companies have spiked, and the stock prices of software companies have plummeted.

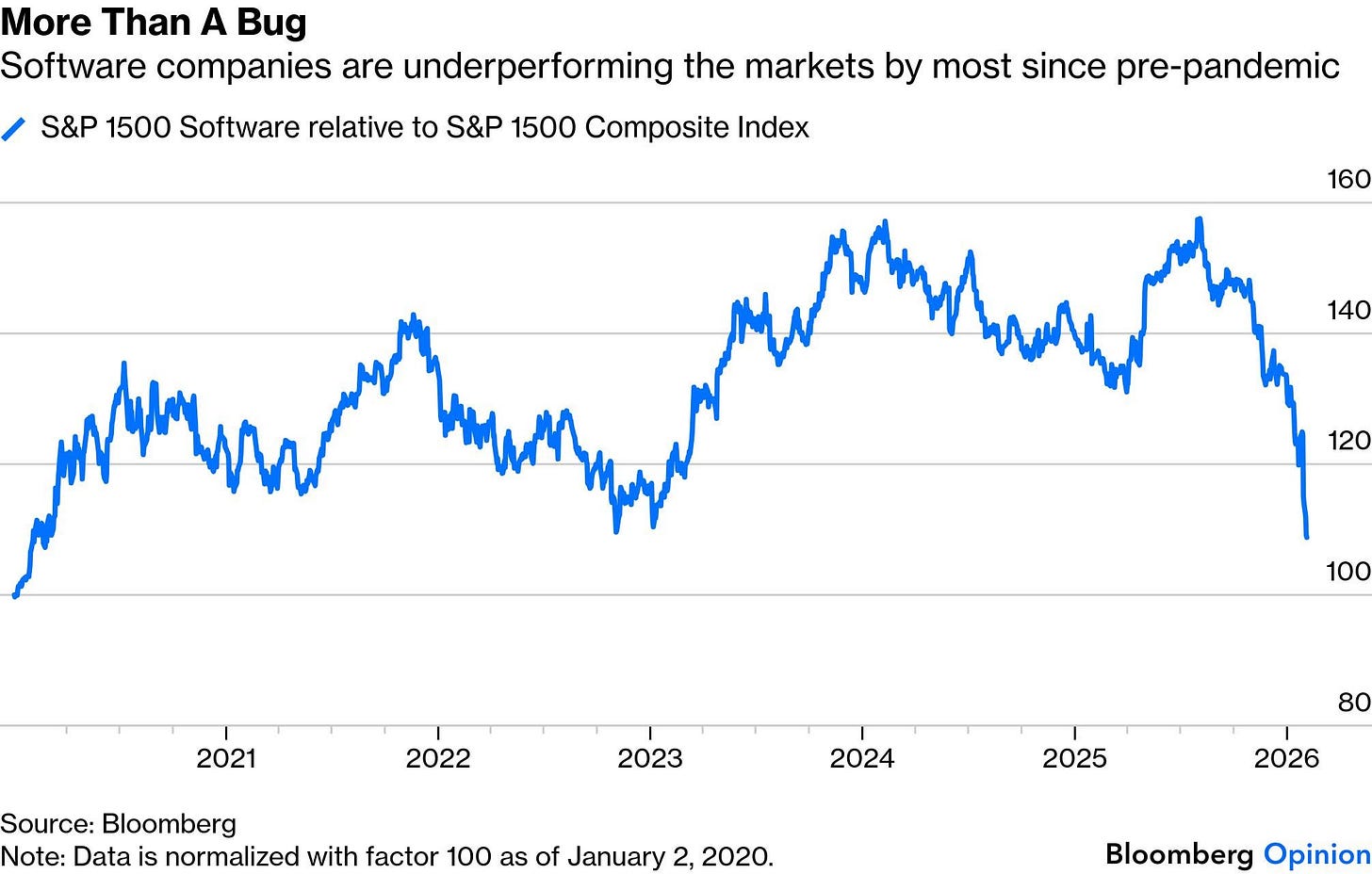

Software stocks have literally erased almost all the gains in the past five years:

Some investors are obviously thinking that AI will inevitably displace software, while others think that the sell-off is ridiculous and it presents a historical buying opportunity for stocks like Constellation Software, Adobe, ServiceNow, etc.

I have recently observed the same divide in our community as well. While some members are skeptical, others believe this is an incredible buying opportunity.

This is why I decided to lean on this topic this week.

I was going to publish a deep dive on an attractive opportunity, but I think everybody is now perplexed by the software sell-off and wants some direction as to whether it’s a generational buying opportunity or really a dying sector.

As somebody who spent his early years as a competition lawyer, built his whole investment philosophy on competitive dynamics, and a PhD in Competition Economics and Policy, I think I have a few words to say about this.

At the end of this write-up, I think everybody will have some cool heads and a grounded perspective to think about what we are really facing.

So, let’s start from the basics—what does “disruption” really mean?

What The Actual Hell Does “Disruption” Mean?

I didn’t want to start from this level, but we have to because some of the posts I see around about disruption are just plain bullshit.

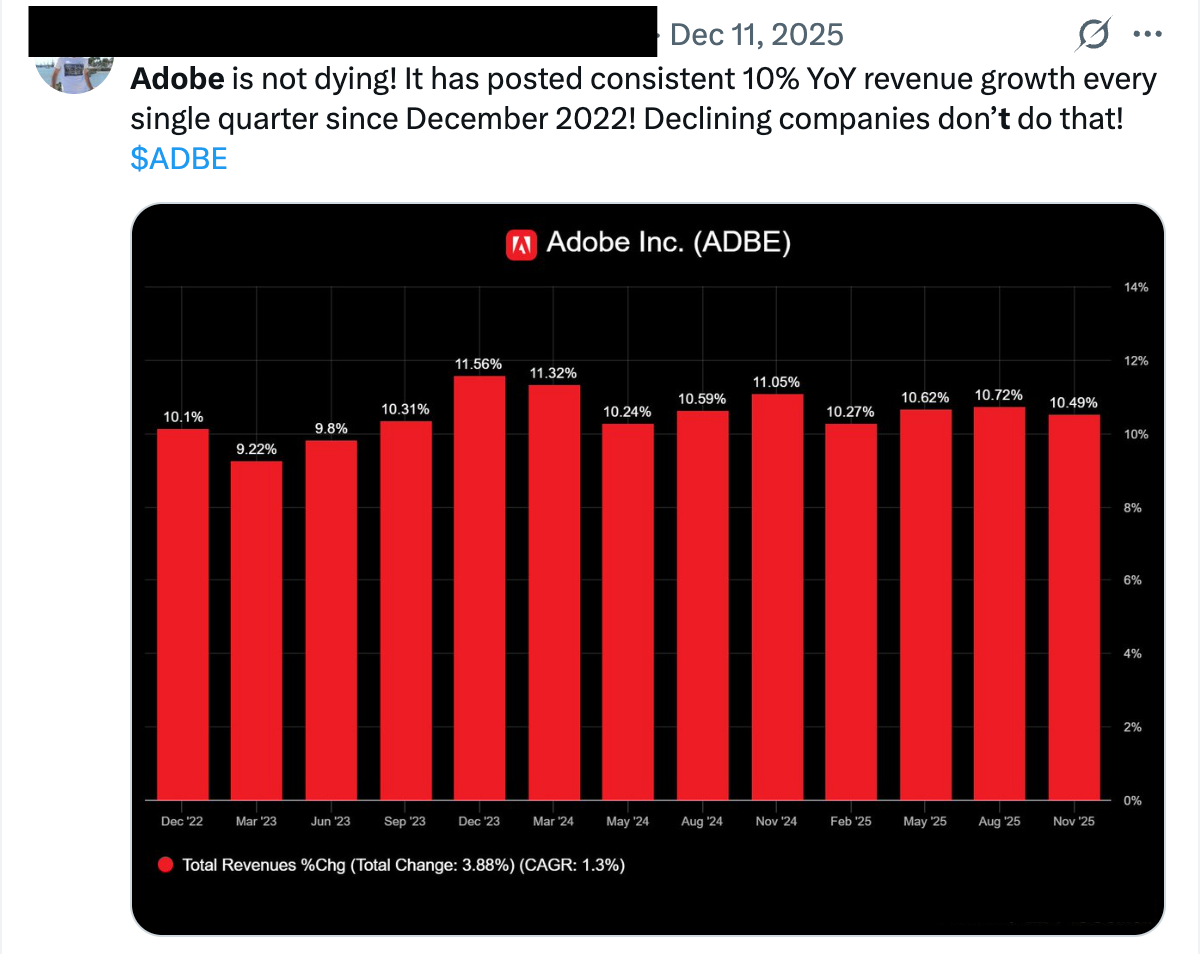

Here is an example:

I have no idea who this guy is, but he isn’t alone. Many proponents of no-disruption are making the same mistake. They are posting a historical growth of the company and say that they couldn’t see a disruption.

To be clear, I am not arguing a case about Adobe here. It may or may not be disrupted; this is not the discussion now. The point is that people are posting historical growth charts of software companies and saying that there is no disruption.

First, if you think that disruption works this way, you obviously know nothing about disruption. Looking at the performance of a legacy business in the infancy of a disruptive technology tells you nothing about the future.

Let’s get some perspective here.

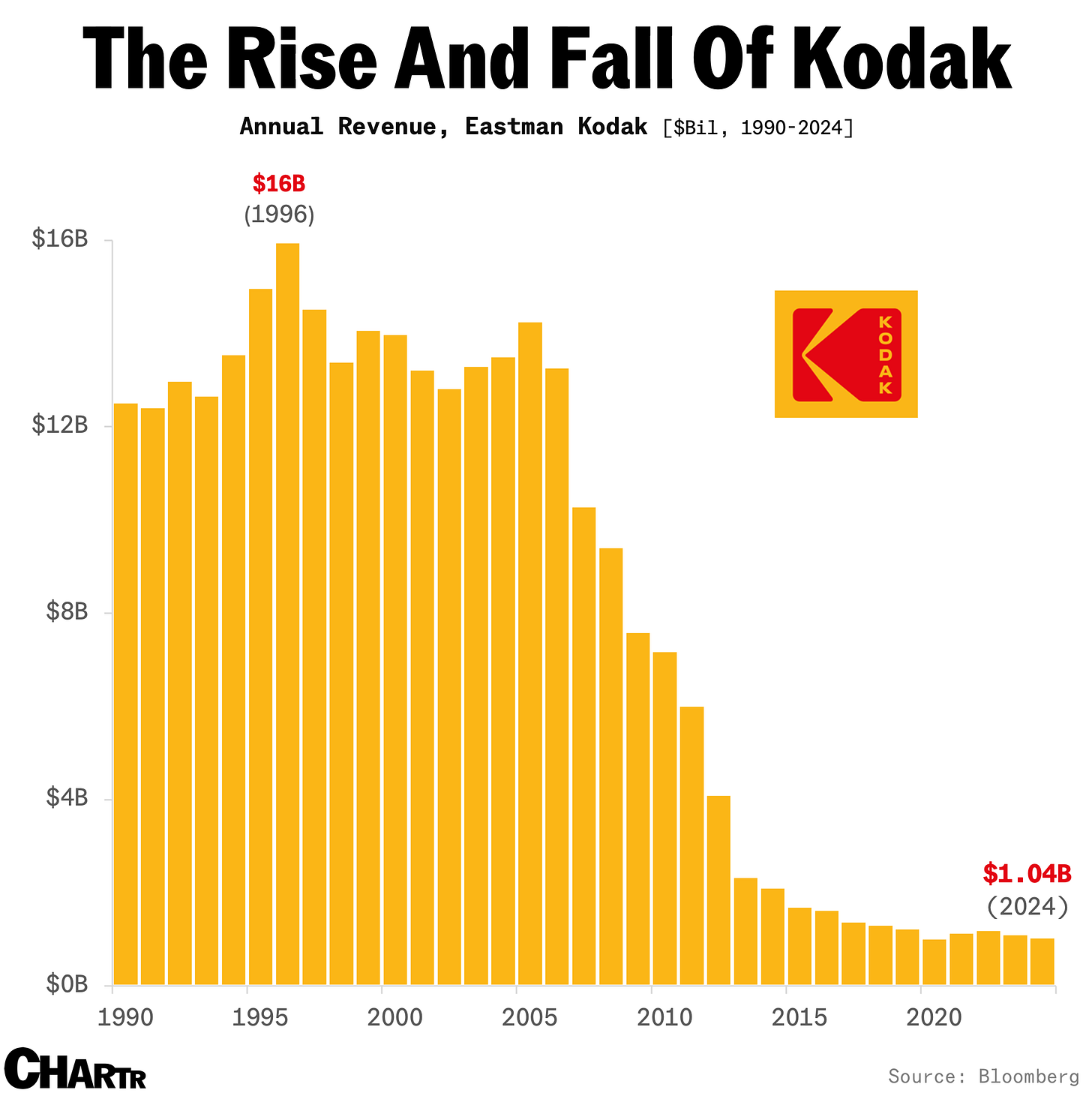

Everybody knows that Kodak was one of the most dominant companies of the 20th century, right? And then it got disrupted by digital cameras. How did it happen?

Here is the timeline:

The first digital camera was invented in 1978.

The first filmless camera was introduced by Sony in 1981.

The first filmless electronic camera was marketed to US consumers in 1986.

What do you think happened to Kodak after 1986? Well, it kept thriving.

Kodak’s revenues peaked in 1996. Fast forward 15 years, and it declared bankruptcy.

Look at every major disruption in history, and you’ll see that, in many cases, incumbents keep thriving for considerable periods after the disruptive technology is introduced.

So, it’s actually meaningless to look at how revenues of incumbents progress in the infancy of a new technology is meaningless. It doesn’t tell you anything about the future. Disruption is not something that happens overnight.

So, arguments like “no sign of disruption,” “people think their moms can code Duolingo now,” “disrupted company doesn’t keep growing,” are totally meaningful arguments, and they only show that those people know nothing about competition and disruption.

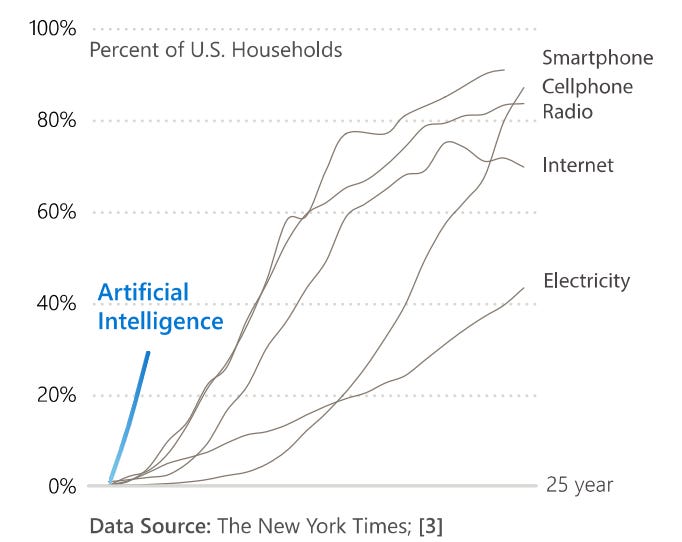

A credible argument that can be made here is that, if there were to be some disruption, it should already have happened, as the diffusion of new technologies is way faster now.

It took 10 years for Kodak to start declining after the introduction of the first commercial digital camera, but AI should show its impact way faster because it’s diffusing way faster.

That could be a credible argument, but history has taught us that impact and diffusion don’t need to progress proportionately, as the runway of new technologies and what they can enable may be massive, and it may take decades to discover full capabilities.

Think about the internet.

In 2006, a person would think the Internet was mature. At around the same time, it enabled cloud computing. A year later, it enabled mobile apps. It enabled digital streaming a few years later. And now, it’s enabling AI as it’s diffusing through the internet.

Thus, whenever we thought the Internet was mature, it was not. It’s probably being more impactful now than it’s ever been by acting as a medium for AI diffusion.

The same thing may happen with AI. It’s possible that we are just in the early innings of discovering the capabilities of the technology. So, it may show its strongest impact even after it reaches full diffusion. We just don’t know where we are.

So, if disruption is not overnight displacement, what is it?

Well, disruption has two forces:

Replacement

Enablement

Replacement is simple. It’s exactly what we discussed above—a service or a product becomes redundant over time thanks to new products or services.

There are two caveats about the replacement effect.

The first one is what we said above. It often takes longer than expected. Legacy products and services often keep thriving after a disruptive new product is introduced because adoption takes time.

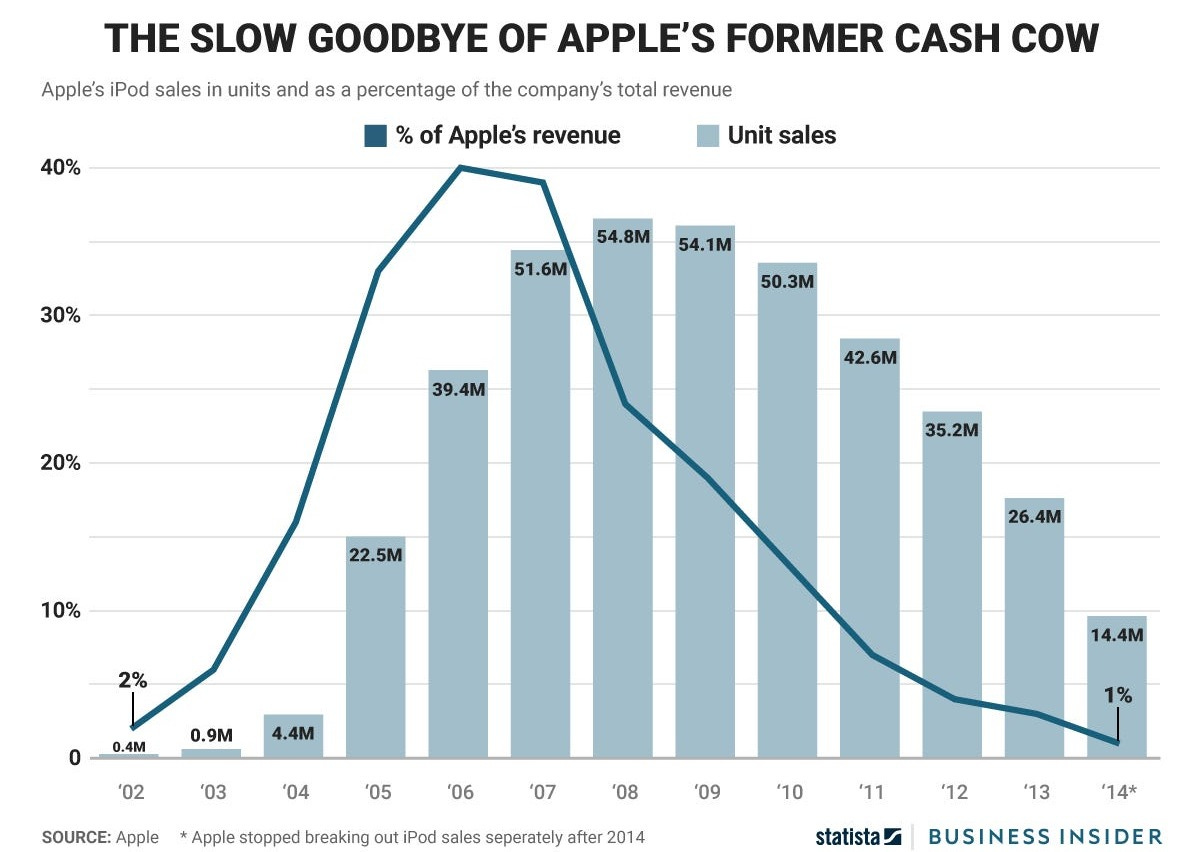

This is the case even in the cases of deliberate self-disruption.

The best near-term example would be Apple’s introduction of the iPhone. When it introduced the iPhone, the death of the iPod was certain, and Apple had known and accepted it.

Yet, iPod sales still grew a year after Apple introduced the iPhone and stayed elevated for the next two years:

Many events of replacement are not this obvious, and diffusion happens way more slowly. As in the Kodak example, it may take more than a decade for a disruptive product to make a dent in the incumbents’ business.

The second caveat is that disruption doesn’t necessarily mean a complete death of the old product or service.

It’s not rare that many products and services transform in their functionality post-disruption. Think pottery.

If you went back 1,000 years, nobody would think of pottery as a form of art. It was mainly a utilitarian activity. People needed plates and bowls to serve food.

However, after kitchenware and dish-making became a completely industrial process in the 19th century, pottery turned into a form of art and thrived in its new form.

This is what you should keep in mind about replacement. It’s a real effect but often takes a long-time to materialize, and disrupted products and services rarely vanish completely. Mostly, they experience a functional transformation.

The second important force of disruption is the enablement effect.

This actually flows from the fact that disruption rarely means the vanishing of the product. It often enables the masses to produce a service or a product that was previously held by small groups.

Think about the textile manufacturers at the time of the Industrial Revolution. A small group was holding the capital, ateliers, and the qualified labor force. It was almost impossible for an outsider to do what they were doing.

After the industrial revolution, it became possible to manufacture textiles by machinery, and you only needed some capital to buy the necessary equipment.

This enabled many people to create textile factories. Result? The product itself hasn’t changed or become redundant, but masses were enabled to produce it.

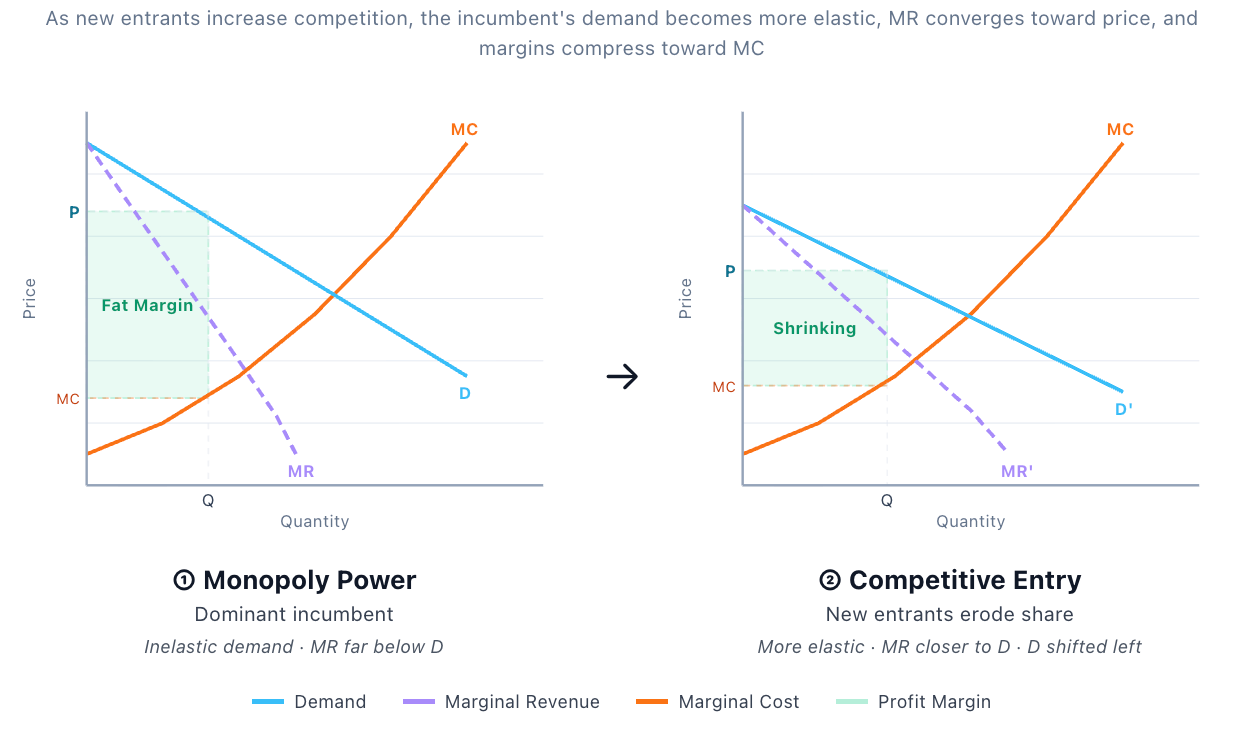

As supply increased, incumbents’ pricing power diminished. As marginal revenue converged toward price, and compressed margins toward marginal cost, incumbents became way less profitable.

This is the enablement effect, and it’s easy to observe this.

Just look at the market rates paid per hour of a junior developer since vibe coding tools entered our lives. Think of their job as a something that was a monopoly market, and other product managers, rocket scientists, and physicists who don’t know how to actually code are now making a competitive entry.

Is this the end of coding? No. Just like we keep producing textiles, we’ll keep producing code. But barriers to producing code are much lower now, so in the long term, we should expect the price of code to come down to near 0.

This doesn’t mean all the code will get cheaper. Pottery got generally cheaper, but some pottery, the state of the art, actually got more expensive. But if you think about it as an index, you can easily say that the price of pottery has come down a lot.

This is what enablement does.

So, we have two disruptive forces. But we also have anti-disruptive forces. This is why every new thing doesn’t replace the old one.

Think about books.

E-books haven’t replaced physical books. Clearly, we have very strong anti-disruptive forces in place, favoring physical books. Thus, while assessing a case of disruption, we also have to look at anti-disruptive forces and make a complete assessment.

Anti-Disruptive Forces

There is no formal way to categorize anti-disruptive forces, but I prefer to divide them into two categories:

Natural

System-induced

Natural forces are always there. They always exist as a natural barrier. System-induced forces appear when a product or a service is connected to other processes to create value.

The most natural force of anti-disruption is inertia.

It’s the natural and reasonable tendency of humans to compare effort and reward from an action. Naturally, such a human tendency also pervades organizations created and run by humans.

For inertia to be overcome, the reward from an action must be more valuable than the effort that action requires.

You could get 10x faster internet in your apartment if you changed the whole infrastructure. But, unless the current speed doesn’t create problems for you, you wouldn’t put that effort and money into having 10x faster internet. It won’t produce a marginal benefit for you.

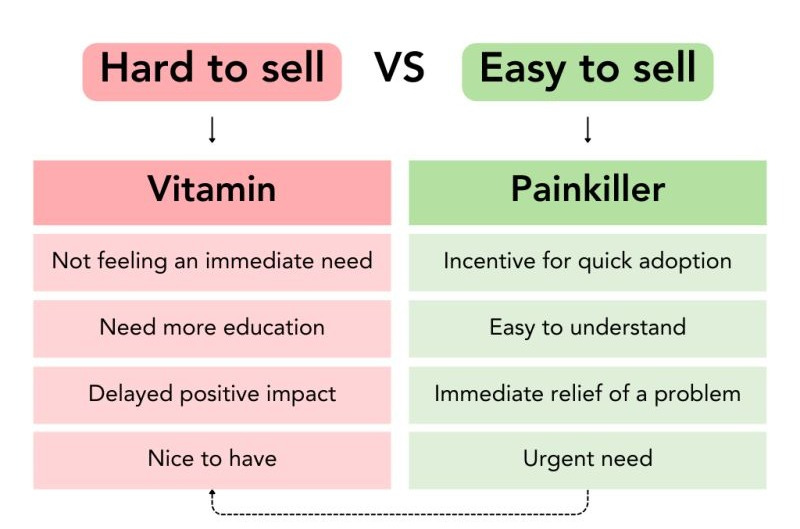

This is why venture capitalists look for painkillers when making investment decisions, not for vitamins. Because of inertia, it’s hard to convince people to pay for vitamins. But if you have some pain, you rush to pay for a painkiller.

Inertia is a law of nature, and it’s the first barrier against disruption. Any new product or service should create a high enough extra benefit to overcome inertia.

E-books obviously don’t meet this threshold for many people, as we keep buying physical books. Streaming, on the other hand, obviously meets this threshold as nobody, except hobbyists, is buying DVDs anymore.

You could go more granular into the natural forces like emotional attachment, etc., but the effect of all are same—creating inertia.

Second are the system-induced forces against disruption.

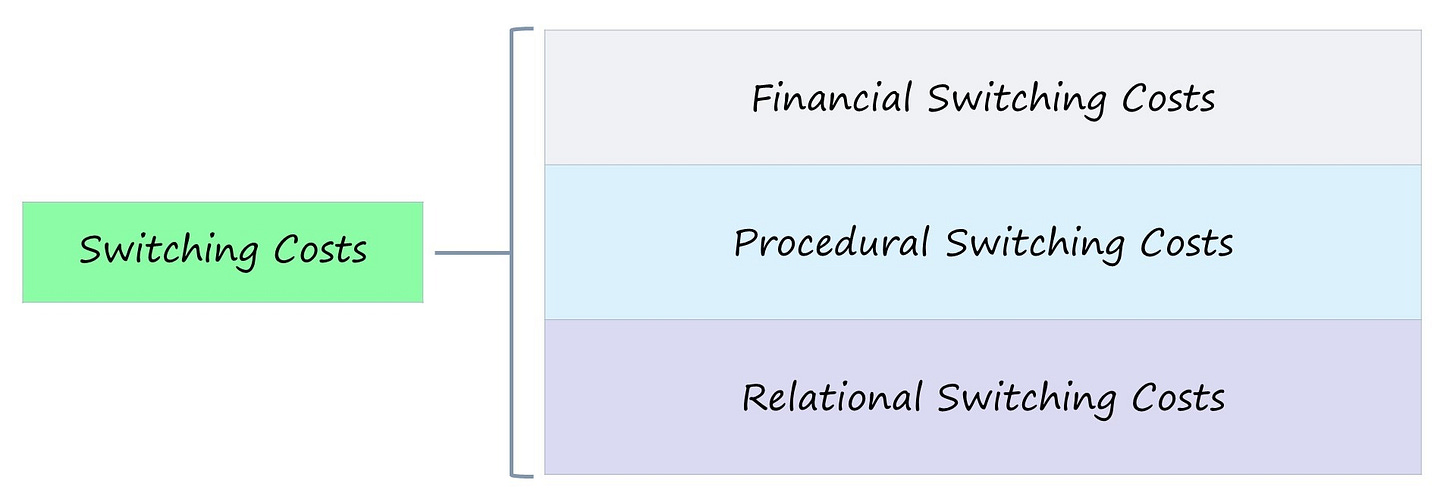

The most effective system-induced anti-disruption force is switching barriers.

Switching barriers emerge when the product or service in place is connected to other processes, and replacing it risks the functioning of the system. In this case, even if there is no inertia, cost-benefit assessment may still keep an organization from switching.

Imagine a spreadsheet program that is way easier and cheaper to use than Excel. Even in this case, it’s really hard to make the switch as:

Auditors expect Excel

Models are shared in Excel

Formulas are understood across teams

Unless other parts of the system also adapt, the switch won’t be value generative.

And when we say switching costs, we have to think about it broadly as all the potential effects that erect barriers to switching. Network effects, for instance, create a form of switching barrier as a customer may lose benefits by switching.

Think about an influencer on Instagram. She wouldn’t switch to a new platform because she would lose all the benefits she derives from having an established audience on Instagram.

There could be an unlimited number of such effects that raise switching barriers. Given that we are limited in space, we can only mention the broader categories. So, if any system-level dependency makes it harder to switch, I consider it within switching barriers.

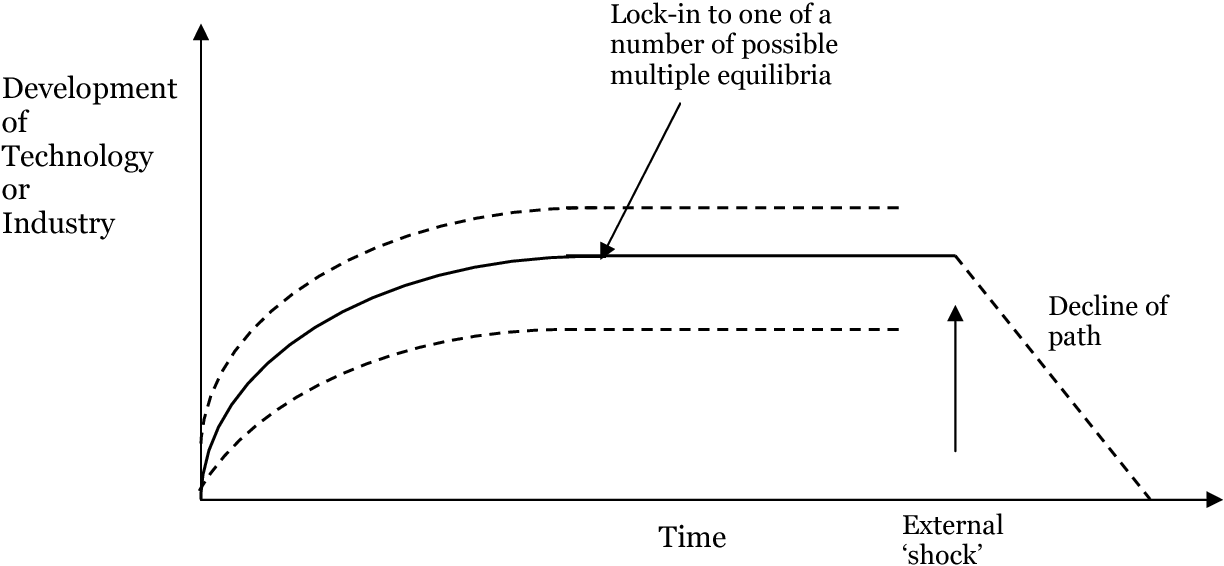

Another broad category of system-induced anti-disruptive forces is path dependency.

Once organizations channel their resources and capabilities into a strategy or decision, it’s costly to turn back from it. Especially if sunk costs are high.

Imagine that you decided to open a dry-cleaning shop in a neighbourhood that had no dry cleaners, but then three other dry cleaners opened before you. Still, no cafe exists in the neighbourhood, but you are already 90% into opening a dry cleaner. You already bought the machines and hired personnel.

You created systems to operate a dry cleaner, not a cafe.

At that stage, you have significant path dependencies. It’s way easier and cheaper to keep going with the dry cleaner, and compete with others, than turning it into a cafe.

For you to go all the way back and turn it into a cafe, the immediate ROI should be so high that it should justify burning the money you spent to open a dry-cleaner and sunk costs for opening a cafe.

When there are path dependencies, the ROI required for change spikes.

Path dependency continues until an external shock destroys the path:

Following the same example, think that 100 more dry cleaners open in your neighbourhood, an external shock. That drives your margins to the ground, and ROI nears 0. Exit was illogical when there were only 3 competitors, now it’s logical. The path has been destroyed by an external shock.

For disruption to happen, forces of disruption should outweigh the forces of non-disruption. That's simple.

Now, let’s turn to software and try to understand how the interaction of disruptive and anti-disruptive forces may play out.

Software: Getting Disrupted Or Here To Stay?

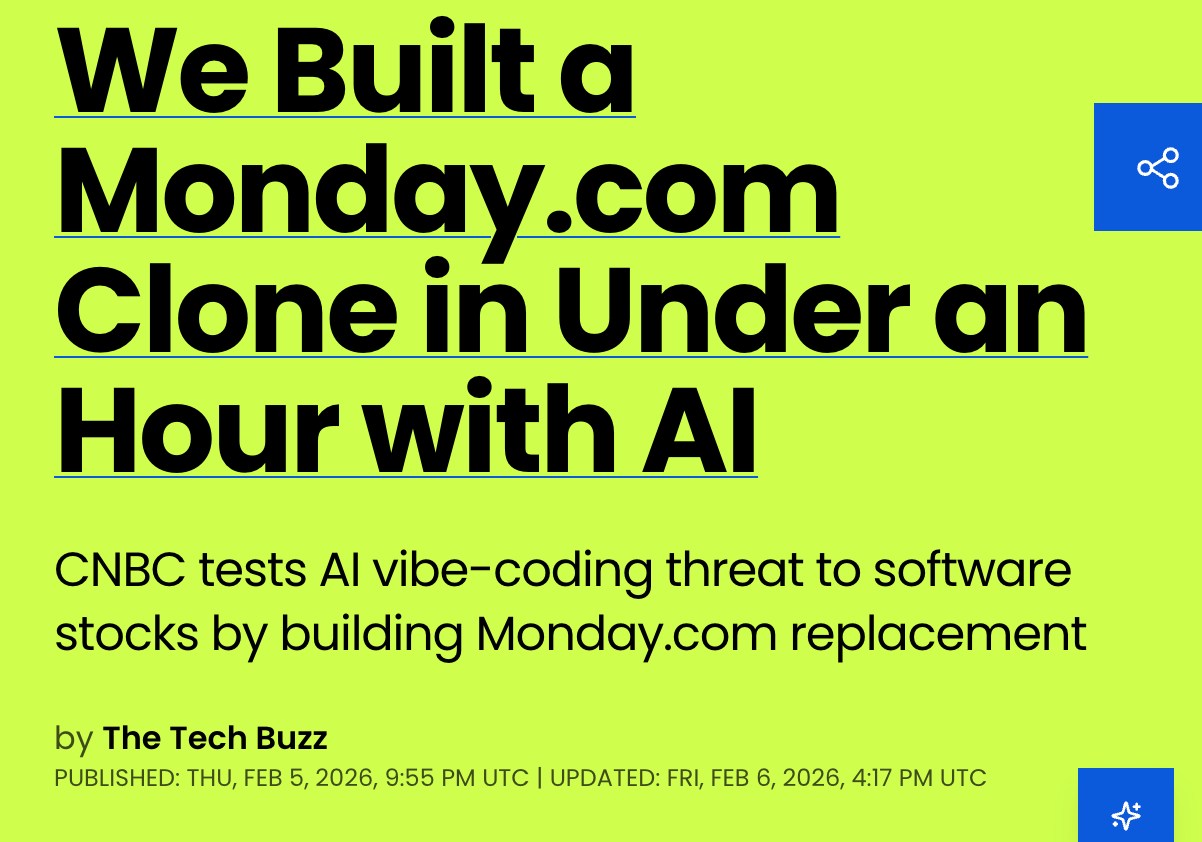

My first observation as to AI’s effects on software is that the force of disruption in place is more of the enablement than the replacement.

AI isn’t making software redundant, but it’s changing how we create software.

This is given.

So, the case of disruption here is not software products suddenly becoming redundant, but the removal of substantial entry barriers, so supply will increase, and profit margins of incumbents will shrink as price approaches marginal cost.

To clarify, this doesn’t mean everybody can now code their own Adobe suite.

However, back in 2015, it was almost impossible for a small team of competent developers to code a full-blown Adobe competitor in a year. Now it’s possible.

It’ll still take time and effort, but at least there is no doubt that replication of the product itself (be careful, I am not saying turning it into a business, just creating the naked copy of the product) in a relatively short term at low cost is possible.

CNBC reporters said that they vibe-coded a functioning Monday.com clone. It was just a primitive version, but it was functioning.

I know the thing they built probably has massive defects, but remember, these are CNBC reporters. Their common trait is being stupid.

If they could build some of the functionalities, imagine what a group of friends from Stanford Engineering could do.

In short, there is a very strong enablement effect coming from AI. Of course, its impact will vary widely product by product. While it’s very easy to create a portfolio tracker, replicating a whole enterprise SaaS suite like Monday.com is still a big challenge. But it’s possible and way easier than it was 5 years ago.

Now, let’s turn to forces against disruption.

Inertia exists for every customer class, but it’s far less for individual customers than for enterprises.

Following the portfolio tracker example, we can easily see that not everybody will create their own portfolio tracker even if it’s easy. Some people will still prefer to pay $5/month than create and maintain their own tracker.

However… As enablement effects are in place, developers will come to take the margins of the incumbents.

There aren’t high barriers to switching. You can just upload your sheet to a new portfolio tracker and continue seamlessly. There is no significant path dependency as we aren’t looking at a complex, interdependent system.

In this case, even if we assume very little switching by existing customers, the market for the new customers will be substantially more fragmented. Thus, the broader market will also become increasingly fragmented over time, and many teams will likely go out of business.

We can model this to 90% of all B2C software, as there are no substantial switching barriers and system dependencies.

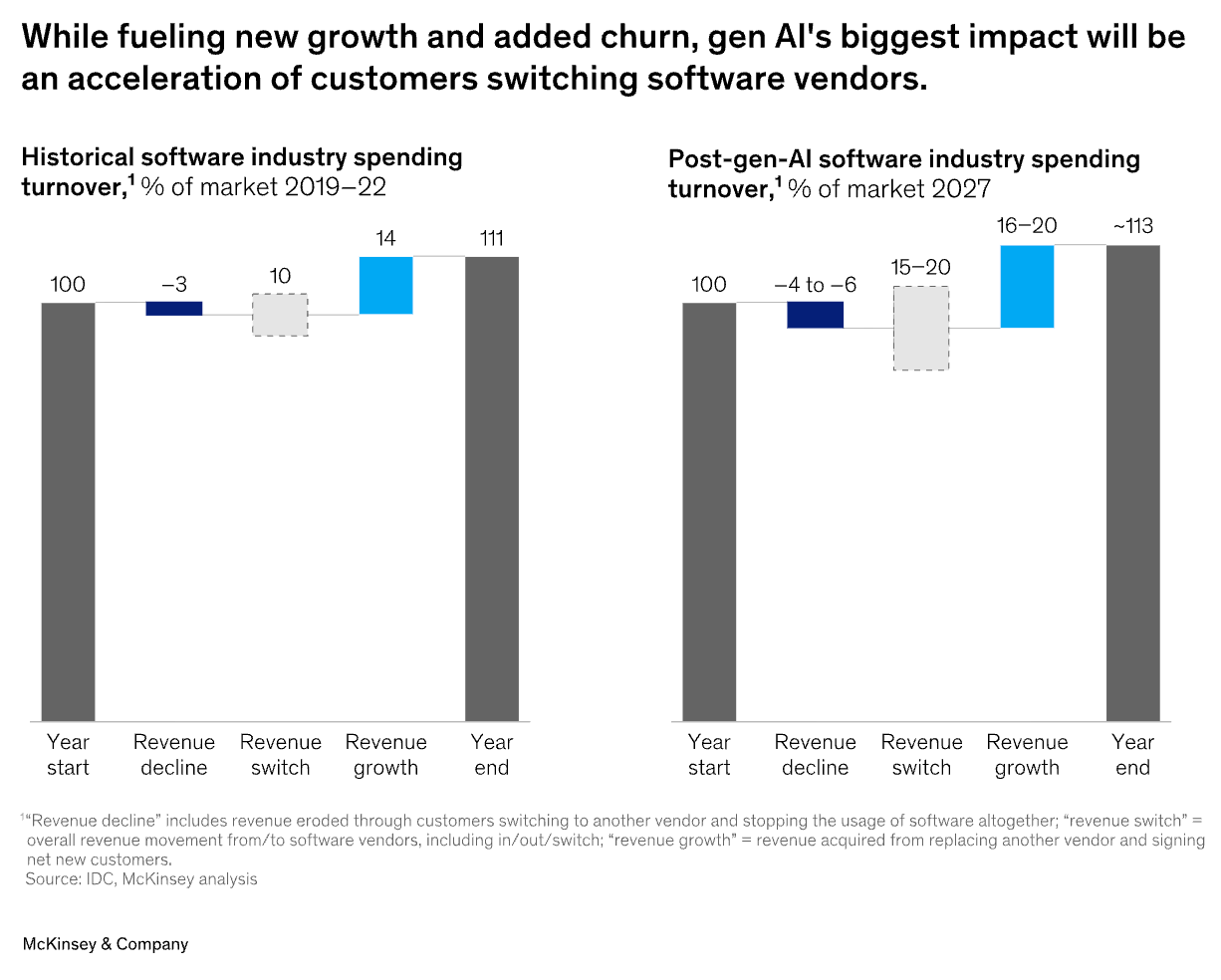

McKinsey also models this as they believe that AI will accelerate revenue switch in software:

Note that their model includes both B2C and B2B software. As B2B has higher switching barriers for the reasons we’ll discuss, we can assume that most of the revenue switch will happen on the B2C side, signaling transformation and disruption.

Of course, there’ll be niches that won’t be disrupted, but generally speaking, we can easily see that there will be waves of disruption in B2C software. It’s inevitable.

We can’t easily say this for B2B software.

B2B software has switching barriers, and it also creates significant path dependencies for customers.

Let’s think about switching barriers first.

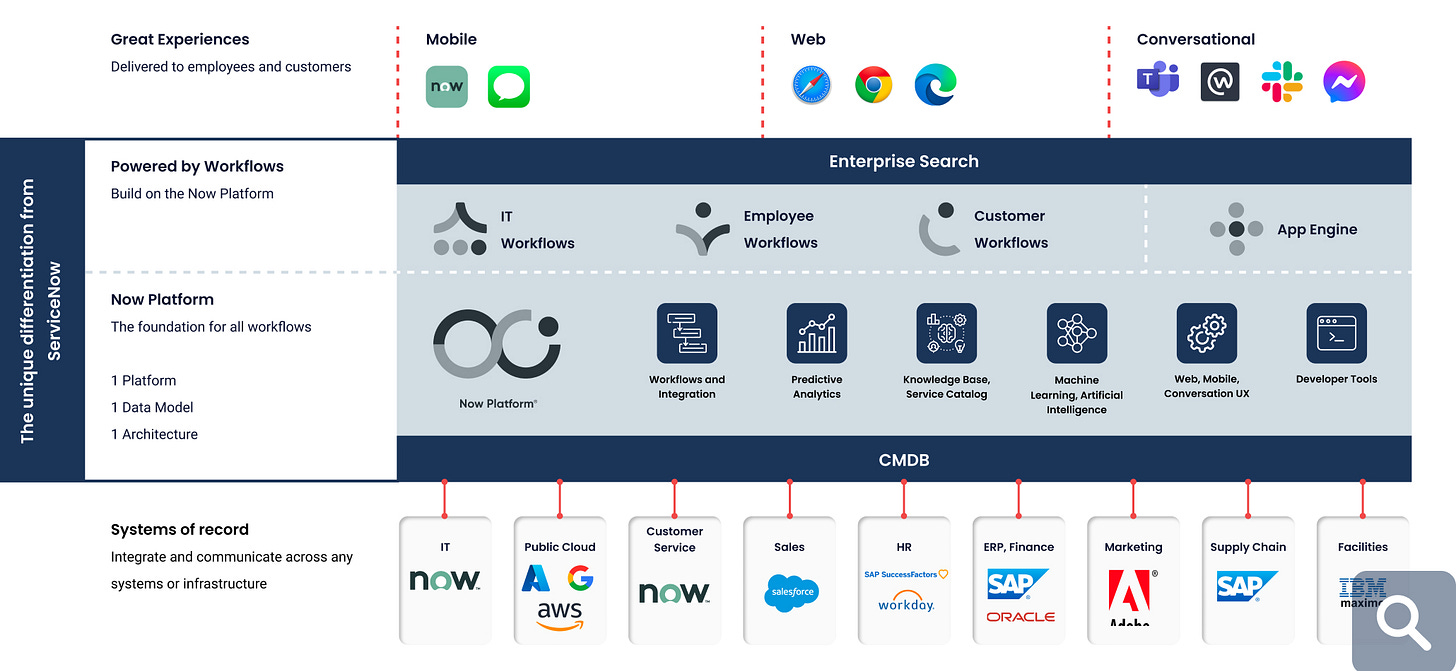

Imagine a software like ServiceNow.

What it basically does is help businesses automate workflows by connecting existing systems.

Imagine a new employee onboarding. When triggered, ServiceNow’s platform triggers a new payroll entry in the payroll software, creation of new email and cloud accounts with relevant service provider platform etc.

It’s basically a platform of platforms sitting on top of the existing systems.

Once you integrate it with all the other systems in your business and you derive value from the orchestration of the system together, you can no longer switch at will.

From that moment on, you have to think from the cost-benefit perspective.

Replacing the ServiceNow platform exposes you to many operational risks like losing efficiency, time, money, etc. Thus, potential gains from replacement should substantially exceed potential costs.

As you could guess, switching barriers also feeds path dependencies.

If your automation layer is ServiceNow, you’ll have to work with systems that are compatible with ServiceNow. This will determine your future selection of systems, creating path dependencies.

Or think about the path dependencies in Adobe.

If you are a creative firm and trained your artists on Adobe, it’s a significant path dependency. You wouldn’t switch to another creative suit just because it’s a bit cheaper.

As you see, the disruption scenario isn’t as easy for B2B software as it is for B2C.

However… If you read carefully, you will get that disruption can happen if the expected benefit goes well beyond the expected costs.

This has a critical implication for B2B software: Pricing power erodes substantially.

For the last twenty years, what we saw was entrenched software companies increasing their prices year-over-year. When this was combined with volume growth, they managed to grow way faster than expected.

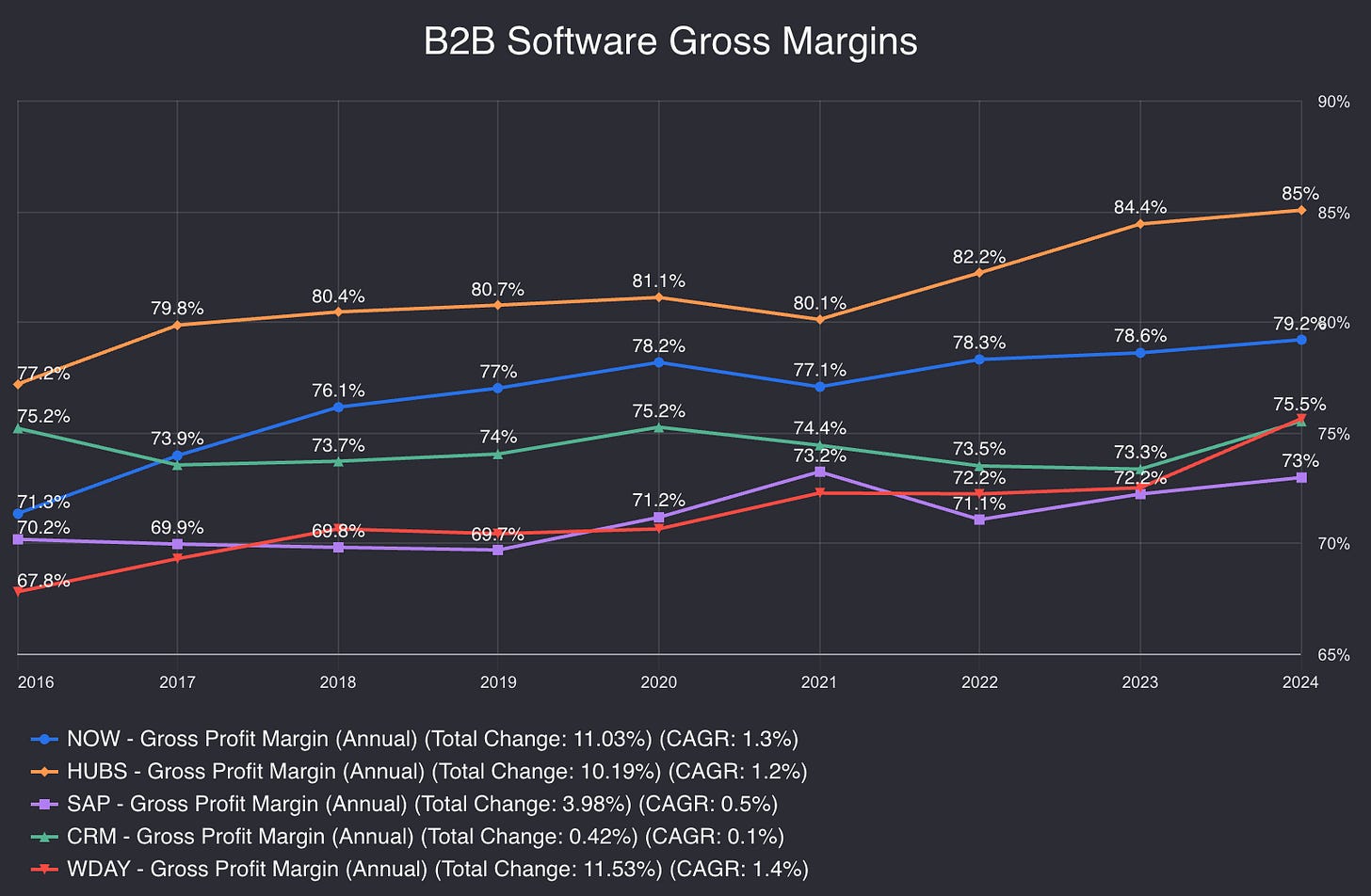

We can clearly see this pricing power by looking at the gross margins of major B2B software providers. They expanded margins considerably in the last 10 years:

Now that the cost of creating software has come down substantially, it’s impossible that this kind of margin profile won’t attract competition.

The crucial point here is that most customers won’t switch initially because of the switching barriers and path dependencies that we explained above. As long as their costs stay stable, cutting enterprise software won’t substantially boost their operating margins.

The key point is that “as long as the costs stay stable.”

If B2B software players keep insisting on raising prices to boost their own margins, it’ll widen the opening for competition. Rivals will likely start creeping into the market, starting from smaller players for whom software makes up a larger share of operating expenses.

We are already seeing this price pressure, though in a different form.

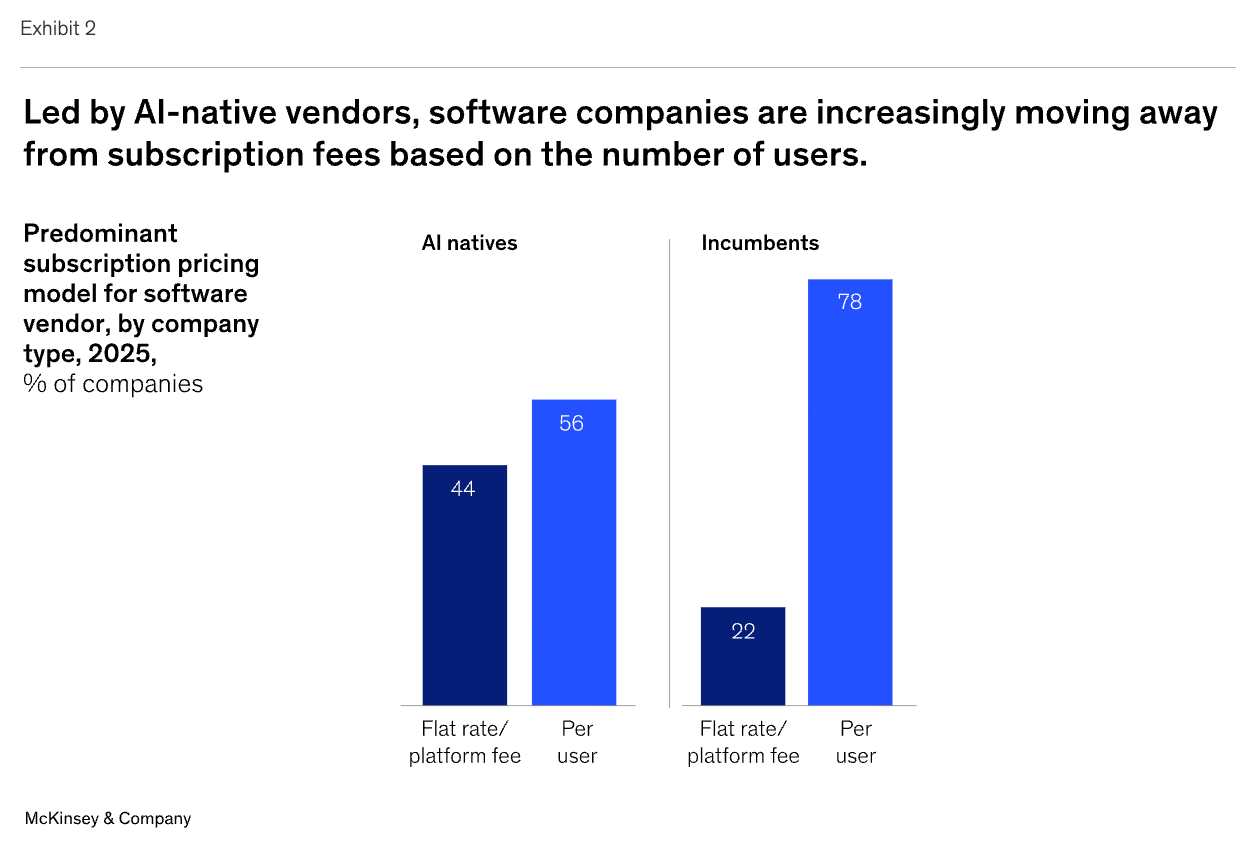

AI native software platforms are increasingly charging flat platform fees rather than subscription fees based on the number of users, which is the dominant model for legacy B2B software:

As this trend continues, legacy providers will gradually lose their ability to charge hefty subscription fees per user and will have to either cut their prices substantially or switch to a platform fee model, which will likely reduce their growth or even revenues.

Incumbents can offset the pricing pressure by cutting their own workforce due to the collapsing cost of creating software. Thus, they can keep their margins even if they reduce prices substantially to keep potential entrants out.

To what extent they can do this depends on the system-level barriers and path dependencies each incumbent faces. The fact that the software can be created by 90% smaller workforce doesn’t mean companies can do it easily, as their corporate structures might have created substantial path dependencies.

So, even though the incumbents can counter the threats from new entrants, it’s obvious that they are facing headwinds.

Another headwind is how incumbents perceive the opportunities created by AI.

Incumbents dominating their own markets think of the collapsing cost of software creation as something that expands their total addressable market (TAM) massively.

They now think that they can more easily attack adjacent markets dominated by other incumbents. This leaves them in a game theory stalemate. If one of them starts the war, everybody will counter, driving the profits to the ground. If they stay still, then there are no real gains from TAM expansion. This is another headwind they are facing.

So, where do all these take us?

Well, B2B software has substantial forces of anti-disruption in place. However, for these forces to outweight forces of disruption, the benefits from inertia should exceed the cost of switching.

This means that the price structure in the industry can’t stay as it was in the last 20 years. If incumbents attempt this, competition will inevitably creep in. On the other hand, they have to be careful not to start a war with the incumbents in adjacent markets, as it will be unproductive for all of them.

Thus, we can think that AI won’t disrupt B2B software anytime soon, but it jeopardizes the growth story.

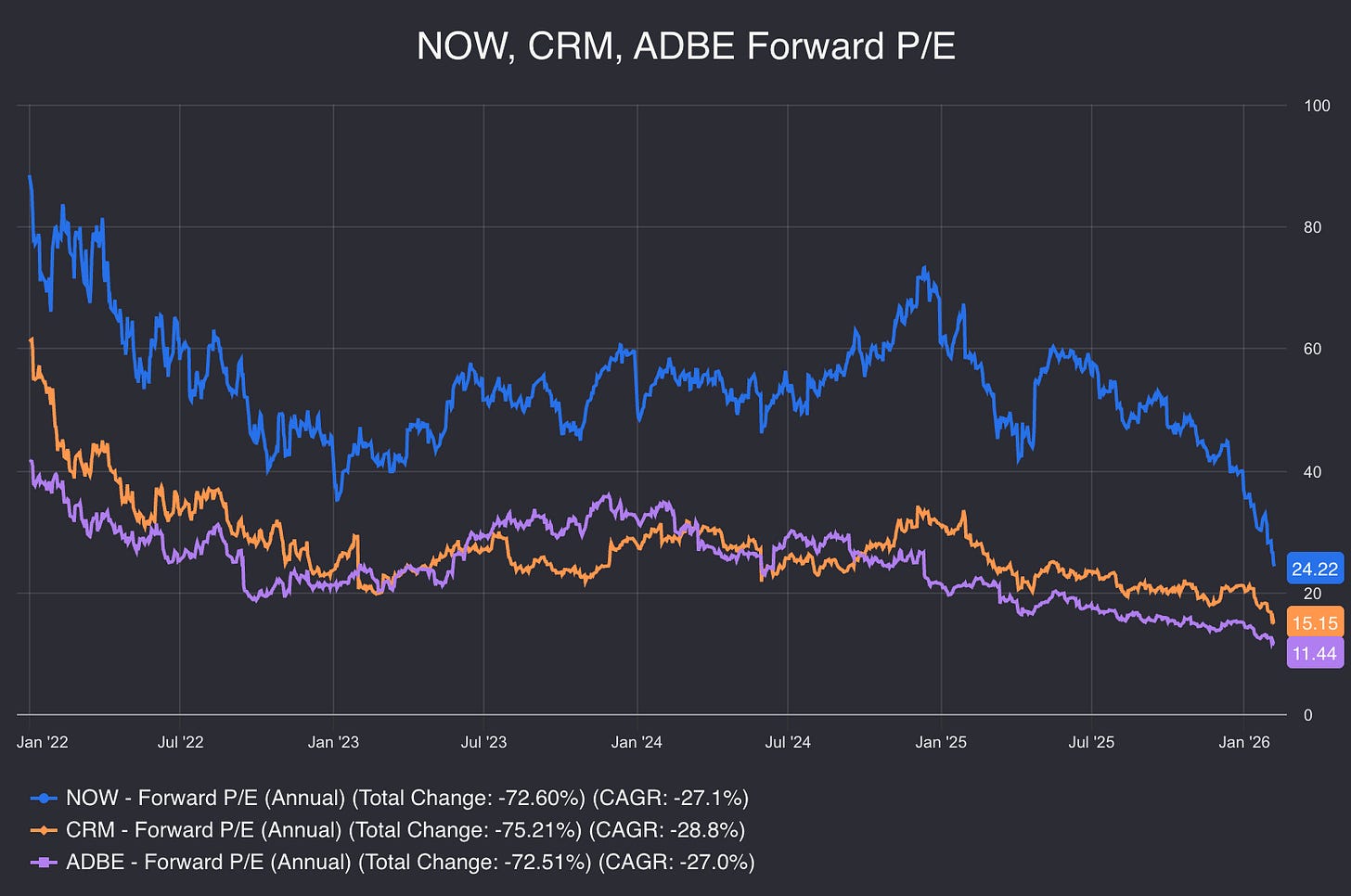

The logical market reaction to this should be a compression in earnings multiples. This is actually what we are seeing.

In the past, you could assume a base P/E of, let’s say 25, and think that a dominant B2B software stock would be attractive at that price. Now, we should readjust our baseline lower due to the risks about the growth story in the medium term, and competition in the longer term.

Now, we should accept that 15x forward earnings may be a reasonable multiple for a B2B software stock.

We are actually seeing this compression in multiples since ChatGPT was launched:

If there are substantial risks to a high-growth story, there is nothing unreasonable about the P/E multiple coming down from 40x to 15x for a software promising 10-15% annual growth in the long-term.

For reference, American Express’ long-term median P/E is about 15 on ~10% annual growth since the 1970s.

So, as opposed to what people suggest, the market isn’t pricing a “death” scenario; it’s pricing in lower growth going forward, which makes sense as we discussed a high-margin, high-growth story should necessarily stop for anti-disruptive forces to outweigh disruptive forces in the medium-term.

Looking at the chart above, I can say all those stocks, NOW, ADBE, and CRM likely offer a favorable risk/reward, but definitely not high-flying returns. Essentially, what you can expect is something similar to what you would expect by buying American Express at 12x-13x forward earnings: Above-market returns, but definitely not a flight.

🏁 Final Words

Disruption isn’t an overnight displacement, as most people appear to think.

Displacement may occur, but total displacement is less frequent than most people think. What generally happens is commoditization through enablement.

Forces of disruption don’t work without obstruction. There are also forces of non-disruption.

While the balance of power is skewed significantly toward disruptive forces in B2C software, forces of anti-disruption are almost equally strong in B2B software, at least in the short to medium term.

Thus, I think there are two consequences that we can draw with confidence:

B2C software will see massive disruption in the coming months and years.

One has to understand nothing about disruption to say B2B software will be disrupted equally strongly in the same period.

As we discussed above, the case for B2B software is a changing growth trajectory and story rather than total displacement. This change should manifest itself mainly through a compression in earnings multiples for B2B software stocks.

We are seeing exactly this since ChatGPT was released.

It’s not an overnight fear mania as many people suggested. If you observe it, the multiples eroded gradually as actors absorbed the development of AI tools and constantly revisited their expectations from B2B software.

Thus, for the medium term, you shouldn’t expect a return to old multiples. There is no reason a B2B software company growing 10% a year shouldn’t trade at 15x earnings. This is basically what companies like American Express historically traded at. Though Amex has lower margins, the lower risk of disruption makes up for it.

Therefore, the reasonable assumption is that ServiceNow won’t swing back to 40x forward earnings. However, there is also no reason why you shouldn’t expect to make money on it if it drops to 20x forward earnings. Then you can expect a reversion to the new base, let’s say 25x forward earnings.

Same for Adobe. We can think that its new base is 15x forward earnings. So, there is no reason that you shouldn’t expect to make money buying it here at 11x forward earnings.

In short, we should understand what the current competitive dynamics imply and arrange our expectations based on them. At this stage, I believe the risk is more on the growth story rather than displacement for B2B software, as argued above.

So, I believe betting on the displacement scenario or the no effect at all scenario will prove equally unproductive. What we are looking at is a battleground of forces of disruption and anti-disruption.

The most reasonable thing to do is rearranging expectation for this battleground.

Maybe buy Adobe at 11x forward earnings and expect it to revert to 15x, but don’t buy something else at 25x, expecting a return to 35x.

I hope this helps.

That’s all friends!

Thanks for reading Capitalist-Letters!

Please share your thoughts in the comments below.

👋🏽👋🏽See you in the next issue!

I work with Stata for macro modeling, and even after trying EViews (which is arguably designed for time series work), I went straight back to Stata. Because my entire analytical workflow, the .do files, the mental models for debugging, the muscle memory for commands that represents years of accumulated path dependency. The cognitive switching cost vastly exceeds any marginal benefit from a "better" tool. This is exactly what you're describing: for B2B software, inertia isn't irrational behavior, it's economically optimal given the system-level dependencies already in place.

Great post. I think you have to be careful on what names to buy. Regardless, some of these SaaS companies have hugh headcounts, and I'm concerned about white collar jobs at these companies in the future. Either the stock will force them to shed bloat, or the AI disruption will.