Oscar Health Revisited: A 10-Bagger In Making Or Doomed To Fail?

An asymmetric opportunity with substantial risks.

Up and down, up and down, up and down… My nine months of holding Oscar can be summarized by these two words.

It would go from a “generational opportunity” to a “shitco” overnight, and repeat this every month.

It’s been a total rollercoaster:

I am not going to lie, it’s psychologically a hard stock to hold. Last time I felt this way, it was for Hims & Hers. It was also a torture to hold. I remember it went down and up more than 40% several times in a year. Yet, it paid off well.

When I say this, some people always scream, “There are easier decisions.” That’s bullshit.

I always remind investors that there isn’t a thing as a no-brainer stock. I also use that term sometimes. When you see it, I use it to make a point, generally to emphasize that a stock is too cheap given the risk/reward profile.

However, a true no-brainer would be like something as follows:

Have a massive and impenetrable moat.

Generate very high returns on investment.

Have a competent management team at the helm.

And then it needs to be cheaply or at least fairly valued, so it’ll really be obvious that we’ll make money on our investment. Such a thing doesn’t exist. It’s a utopia.

If the conditions for a great company existed so obviously, the stock wouldn’t be cheap. If the stock is cheap, either the conditions don’t exist, or there are questions about or risks to their sustainability, i.e, uncertainty.

If you think it’s an easy decision, you likely don’t know the risks enough, so you are underestimating them.

Three months ago, everybody would say Fiserv was an easier decision than Oscar. It’s a banking software & payment acquirer, 4-7% organic growth can be expected, and it was trading at 12x forward earnings. We all know what happened next.

Four months ago, Google was $150, and when I said I was bullish on Google, many people said there were easier decisions; now the same people say it was obvious.

So, let’s remember that “easy decision” is just an illusion; no easy decision exists.

This is why we have to deal with cases like Oscar and make decisions if we want outsized returns. Otherwise, we would be stuck with seemingly easy decisions like Fiserv, and we would have to put a lot of money into them to move the needle because the upside potential was limited, and we would end up losing a lot of money.

In cases like Oscar and Hims, the massive upside gives you the luxury of allocating smaller amounts. If you aren’t blinded by greed and limit position sizes appropriately and manage the catastrophic risks by proper diversification, you can move the needle while not exposing yourself a devastating downside risks from any single position.

This is why cases like Oscar and Hims are worthwhile, and we are operating in this sphere despite the psychological torture.

It’s now been exactly 7 months since I publicly published my Oscar thesis.

The stock is up nearly 40% since then, and those who bought the stock shortly after the thesis have made nice money. Though not bad, 40% is nothing, given the potential of the company.

I assume many in our community are already familiar with the thesis about this company; however, our readership has nearly doubled since I published the thesis, and 7 months is a long time, even for those who read it back then.

So, in this update, I’ll

Go through the investment thesis

Discuss how it can be affected by potential changes in ACA subsidies.

Provide two alternative valuation models based on positive and negative outcomes regarding the ACA subsidy extension.

Let’s get started.

Oscar Investment Thesis: A 10x Opportunity?

➡️ The Business of Oscar

I love insurance companies, just like Buffett.

Buffett likes them because he gets to invest the insurance float and keeps the excess returns the float generates. That excess return becomes permanent capital that you can reinvest as you wish.

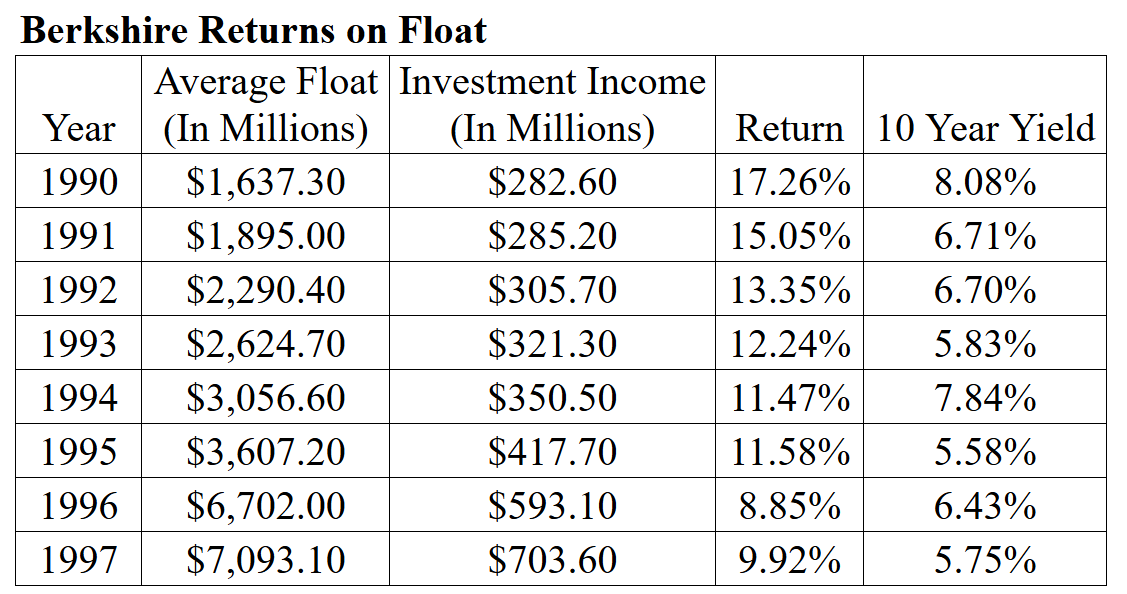

Buffett generated great returns on Berkshire’s float, bought new companies with it, and built the Berkshire we know today:

I don’t have any business with the float. I like insurance for other reasons, for structural reasons:

It’s a sticky business.

It’s a defensive product in nature.

The total addressable market is immense.

For these reasons, it’s not uncommon that successful insurance companies become 10-baggers in the stock market.

Why is this the case? It’s simple:

People rarely change their insurance company as carriers discount premiums for existing members. This means that the business can easily grow even if it adds only a few new users every year. Churn is already minimal. It’s further reduced by the fact that people prioritize insurance payments in all economic environments, as protection against catastrophic risks is of paramount importance.

When the above factors meet with a massive addressable market, they enable successful insurers to grow high single digits for decades, a recipe for 100-baggers.

Now, all the factors above are even more pronounced in health insurance:

It’s more sticky.

It’s more defensive.

The addressable market is literally everybody.

This is why even slightly successful, above-average quality health insurance companies tended to do very well in the market.

I am not even talking about just the market leaders like UnitedHealth and CVS. Average companies like Centene and Elevance have made more than 10x since they became public, and Molina is getting there.

It’s been an industry where the upward trajectory is nearly guaranteed once you carve a bit of ground for yourself in the industry.

Though this is good for the companies, it signals a broken industry with significant incumbency bias and thus inefficiency. This happened because the US healthcare system has been broken since World War II.

It started with the adjustments to support the war economy:

During the war, the Federal government imposed wage and price controls to combat inflation.

The War Labor Board exempted employer-sponsored health benefits from these wage freezes, making health insurance an attractive non-wage benefit to attract workers in a tight labor market.

This is how the employer-sponsored system took off. By the war’s end, health coverage had tripled. The 1948 IRS ruling exempting employer-provided health benefits from income taxation cemented the system. This basically tied health insurance to employment.

Employees wouldn’t pay any taxes on the value of employer-sponsored healthcare, and employers would be able to deduct their healthcare payments from taxes. This made health benefits a tax‑favored form of compensation compared with wages.

Though it looked like it made sense for both employees and employers, it hurt the system in the long run:

The lid on healthcare premiums weakened. Corporations would deduct them from taxes, reducing their price sensitivity.

Insurers and care providers constantly raised their prices, exploiting corporations’ paying power.

Healthcare costs skyrocketed, making individual plans inaccessible.

At some point, skyrocketing started to hurt employers much more than they were willing to tolerate.

Employers responded by increasing deductibles and employee premium shares and by offering leaner benefits, so coverage quality and financial protection eroded for many workers at the bottom and middle of the wage distribution.

Coverage for high earners largely remained intact, as the tax exclusion is larger in dollar terms for higher tax brackets. They enjoyed richer, more heavily subsidized coverage while low-wage workers effectively got empty policies.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) was enacted to address this problem by bringing the costs down in the individual market and expanding access to higher-quality coverage.

The ACA established health insurance marketplaces in every state and required all individual and small-group plans sold on them to cover a standardized package of Essential Health Benefits.

Marketplace plans are subsidized by the government based on income through premium tax credits (and cost-sharing reductions for lower-income enrollees), which makes higher-quality coverage affordable while limiting out-of-pocket exposure.

That created a massive new market.

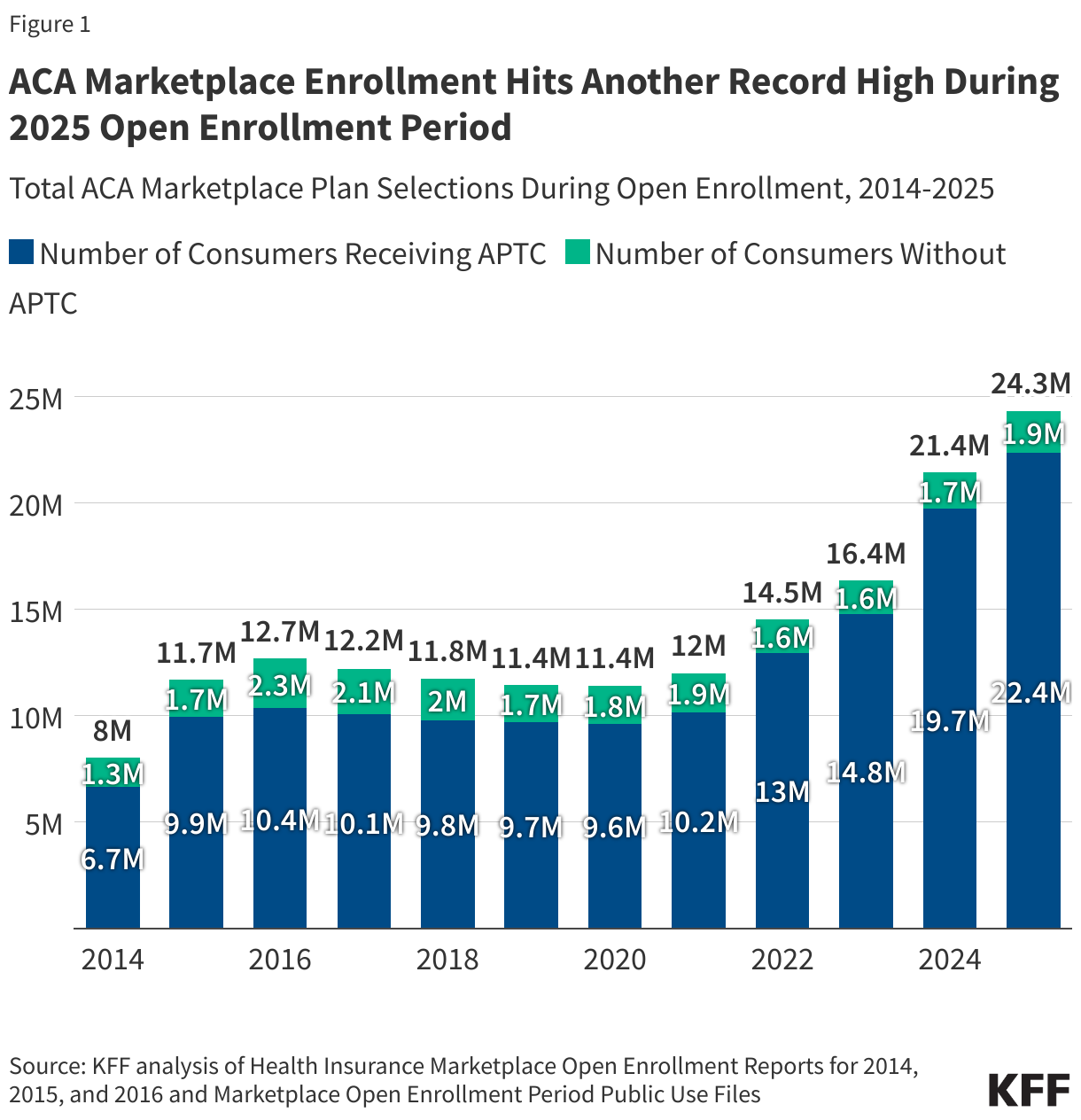

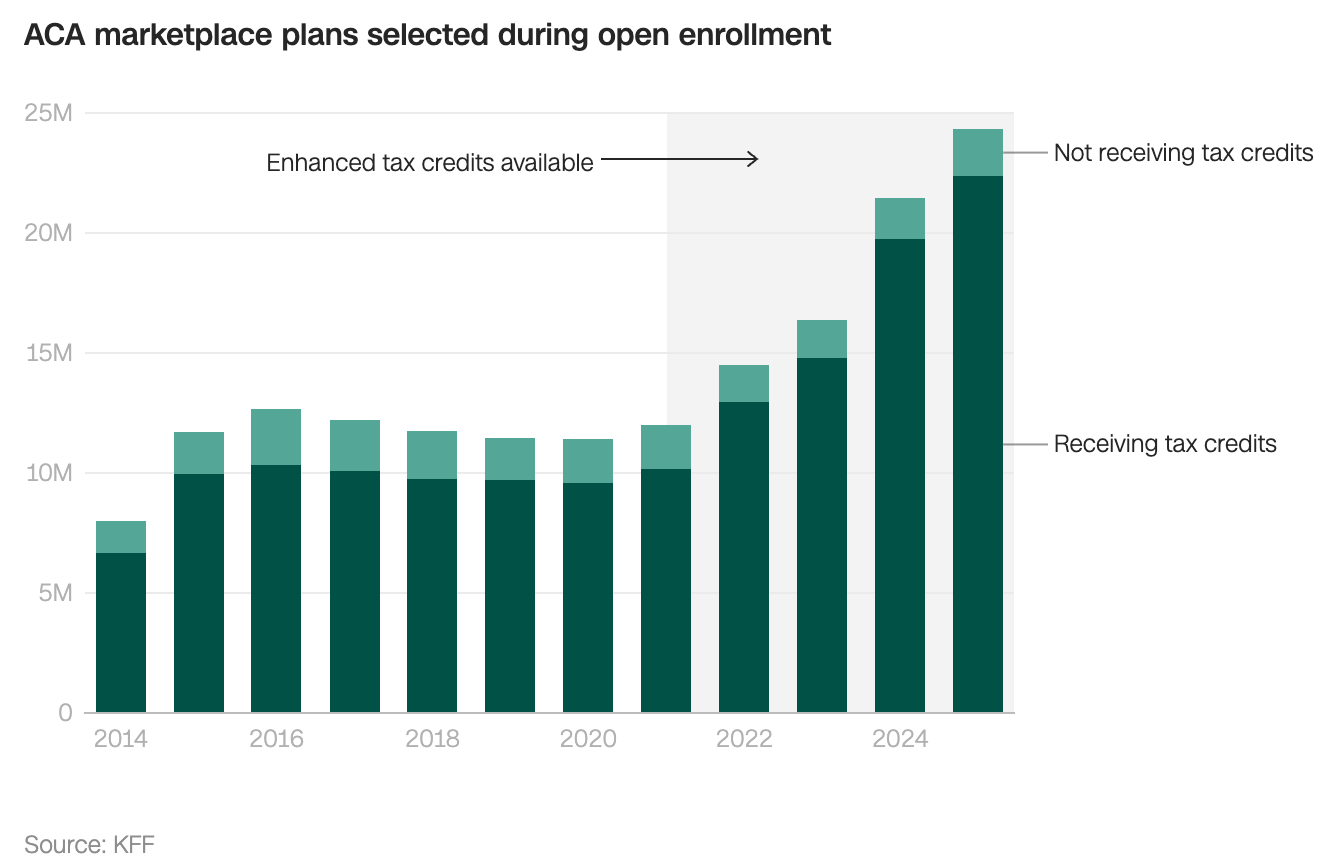

ACA enrollees reached 24.3 million in 11 years since the first enrollment in 2014:

The scope of the market was widened even further back in 2020. The government allowed employers to pay tax-free allowances to buy their own ACA-compliant health insurance. It was a win-win model for both employers and employees:

Employers could still deduct allowances from taxes.

Lower-income workers wouldn’t be stuck with low-quality group coverages.

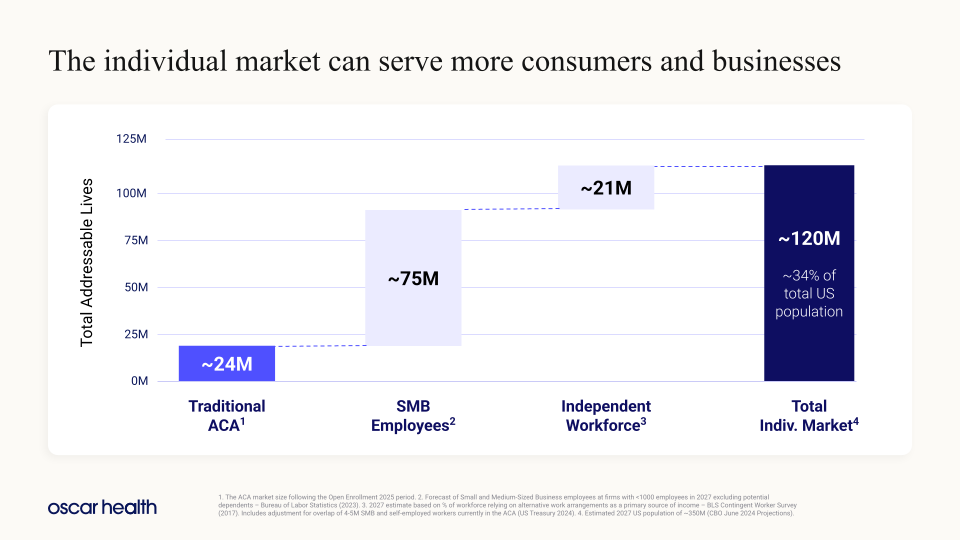

This basically boosted the addressable market for individual health insurance from 21 million people to a whopping 96 million people. A massive opportunity.

Oscar was one of the early movers in this market.

After the enactment of the ACA, founders Joshua Kushner and Mario Schlosser moved quickly to capitalize on the opportunity. They founded Oscar in 2012, spent two years preparing, and entered the market in 2014 with the first enrollment window.

Oscar enrolled over 40,000 members and reached $180 million in revenue in its first year, and never looked back, growing into a $4.5 billion company in just 10 years in a market where incumbents were entrenched, and entry barriers were high.

This kind of setup always makes me feel very bullish for the business because it essentially signals two essentials:

The business has a competitive edge given that it entered and thrived in a market defined by entrenchment.

The competitive edge will get even stronger as it has now also become an incumbent, benefiting from entrenchment effects.

The competitive edge that this business signals is integral to the thesis.

➡️ Oscar’s Competitive Edge

In insurance, pre-acquisition competition is high while it plummets post-member acquisition. This mandates different strategies in different phases.

Pre-customer acquisition, you compete.

Post-acquisition, you retain.

Given that the product itself is mostly a commodity, there aren’t many strategic routes companies can take. Pre-acquisition, they compete on price, and service is what matters post-acquisition.

The critical factor is that a cyclical relationship between the price and service exists. Operating costs and morbidity turn back and affect the prices you charge. Yet, in a legacy operation, you don’t have much to cut costs without sacrificing the service.

Oscar heavily relied on technology to achieve this.

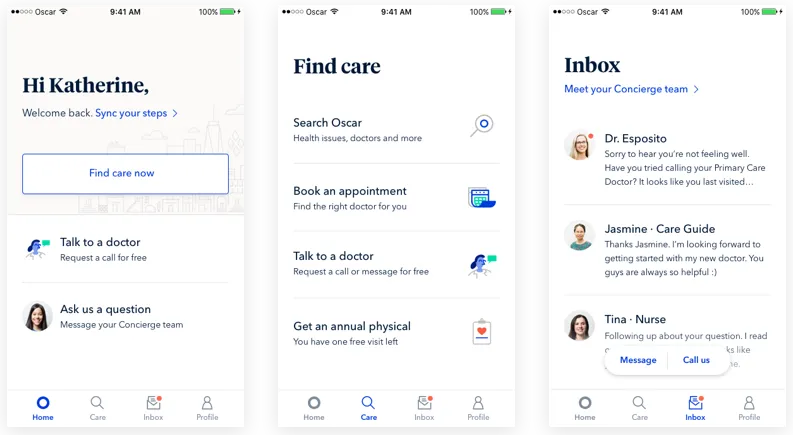

They created what they call “healthcare-as-a-service” model. They created a cloud native platform where you can:

Buy insurance in 5 minutes.

Send a direct message to a personalized concierge to find the right doctor and learn about costs.

Schedule virtual visits mostly for $0 additional contribution.

Get personalized care recommendations based on your past.

File and track claims, see bill explanations, and pay bills.

There are obvious and hidden effects of this model.

The obvious effect is that platform platform-centric, tech-driven model allows them to significantly cut costs. Instead of employing humans for claims processing and customer service, they used machine learning models, cutting costs and improving responsiveness.

The non-obvious effect is that it allowed Oscar to better control morbidity. Instead of avoiding customer activity at all costs, Oscar tracks members’ condition, and prompts them to take small actions to avoid further morbidity.

For instance, imagine you have chronic pancreatitis. Oscar encourages you to schedule an appointment regularly with a provider to keep it under control, to avoid deterioration that could result in a major surgery.

Elevated morbidity control results in lower medical costs and bumps customer satisfaction:

Oscar’s net promoter score is 66, while the average of the top 25 providers is just 29.

Oscar’s medical loss ratio was 88.5% last quarter, while major providers like UnitedHealth, Centene, and CVS had it between 88.9% and 93%.

Oscar passes some of its cost savings to members and offers lower prices than the competitors, with higher network flexibility:

Lower pre-acquisition prices combined with higher satisfaction post-acquisition create a significant competitive edge for Oscar.

As a result of this edge, it has literally entrenched itself in the market and has become one of the leading players in ACA plans. Currently, 25 million people are enrolled in ACA plans, and 2.1 million of them are Oscar members, giving it an 8.5% market share.

For reference, UnitedHealth, as the leader in the broader industry, has just 15% market share. With this perspective, what Oscar has achieved in its niche becomes more impressive.

This competitive edge strengthens in a self-sustaining manner as it grows further, benefits more from the technology and agentic systems, and gains more bargaining power in the industry as it grows in size.

➡️ Performance & Fundamentals

Oscar’s performance proves its competitive edge and effectiveness in ACA plans.

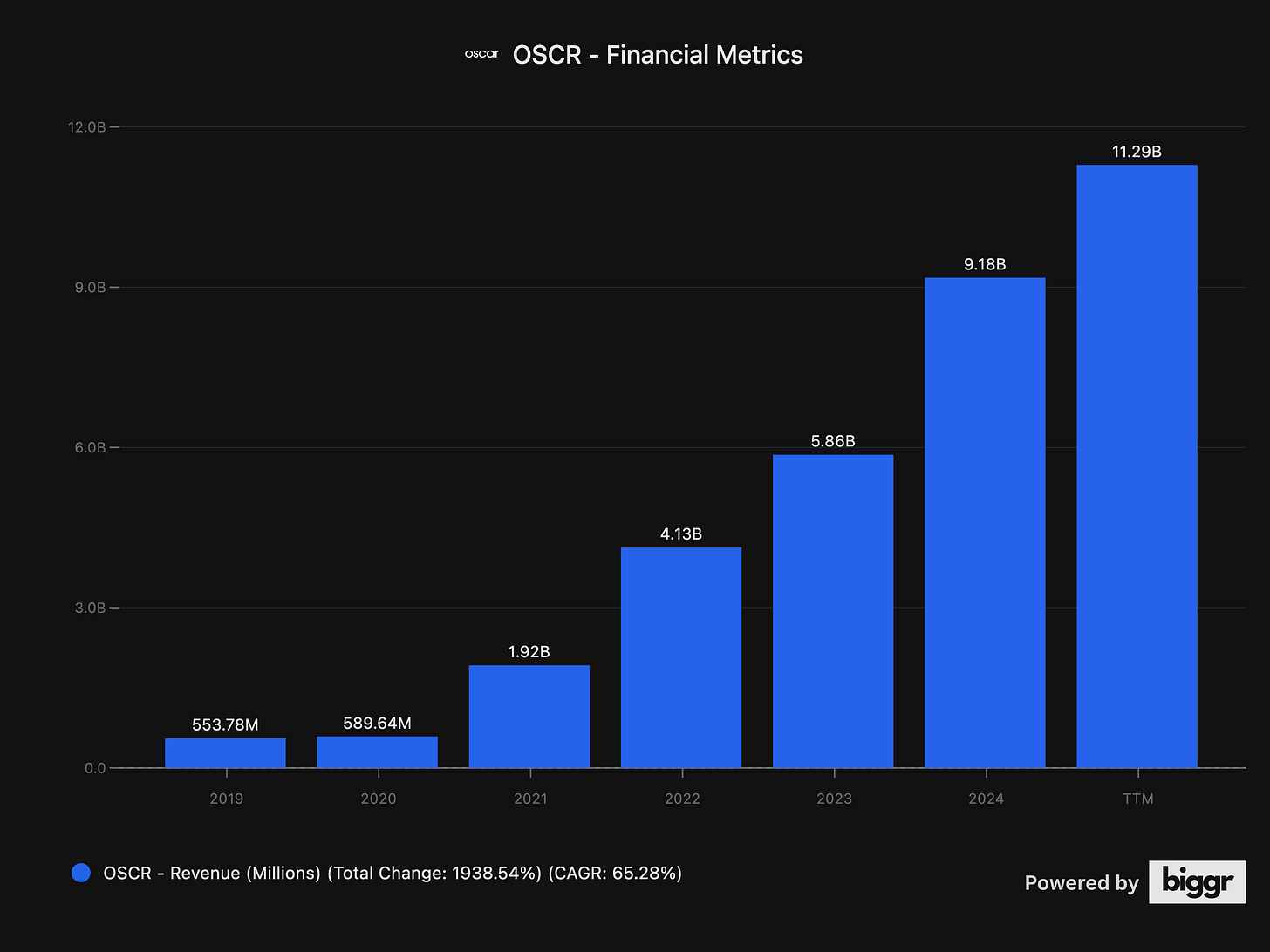

They have grown revenues literally 20x from $550 million levels in 2019 to $11.3 billion in the last twelve months, and they are guiding for $12 billion for the full year.

This growth, of course, was driven partially by increasing healthcare costs and prices but largely by their neck-breaking member growth. They had just around 230K members in December 2019, which has grown by 9x since then and reached 2.1 million for the last twelve months.

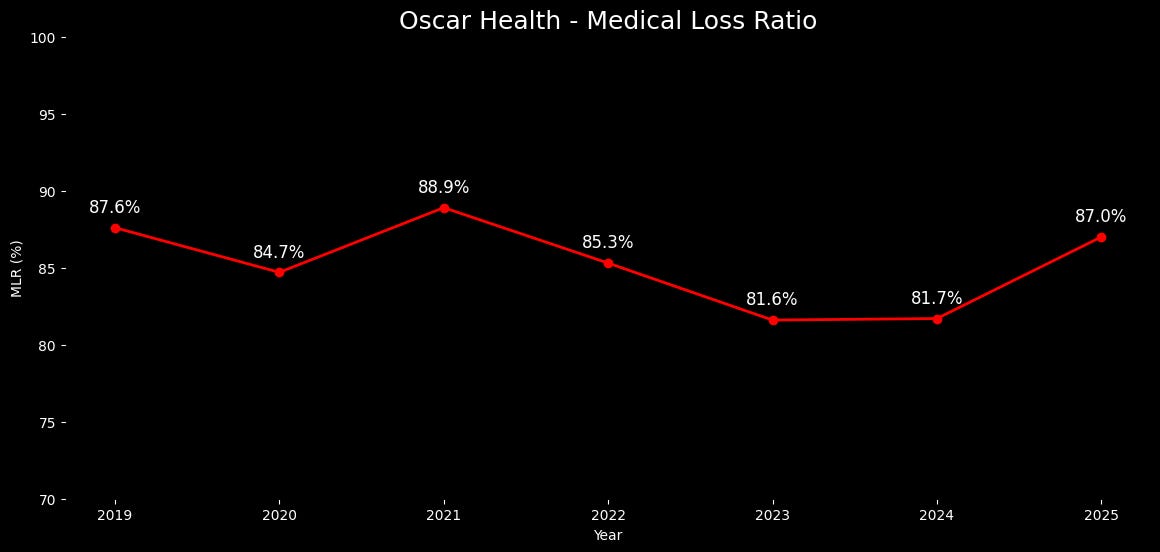

What’s really impressive is that they have managed to gradually but consistently reduce the medical loss ratio (MLR) while they were growing pretty fast. They didn’t compromise on the operational discipline.

Their MLR declined from 87% in 2019 to 81.7% in 2024:

As a result of this decline, they became profitable last year for the first time. Normally, they had guided for sustained profitability this year, but the whole industry is struck by unexpectedly high morbidity and medical inflation. This is why MLR jumped this year, and they are looking to finish the year with 87% MLR.

This isn’t good, of course, but the good news is that it’s industry-wide, not specific to Oscar. Further, Oscar will still have a lower MLR than the industry giants, again validating its operational efficiency and competitive edge.

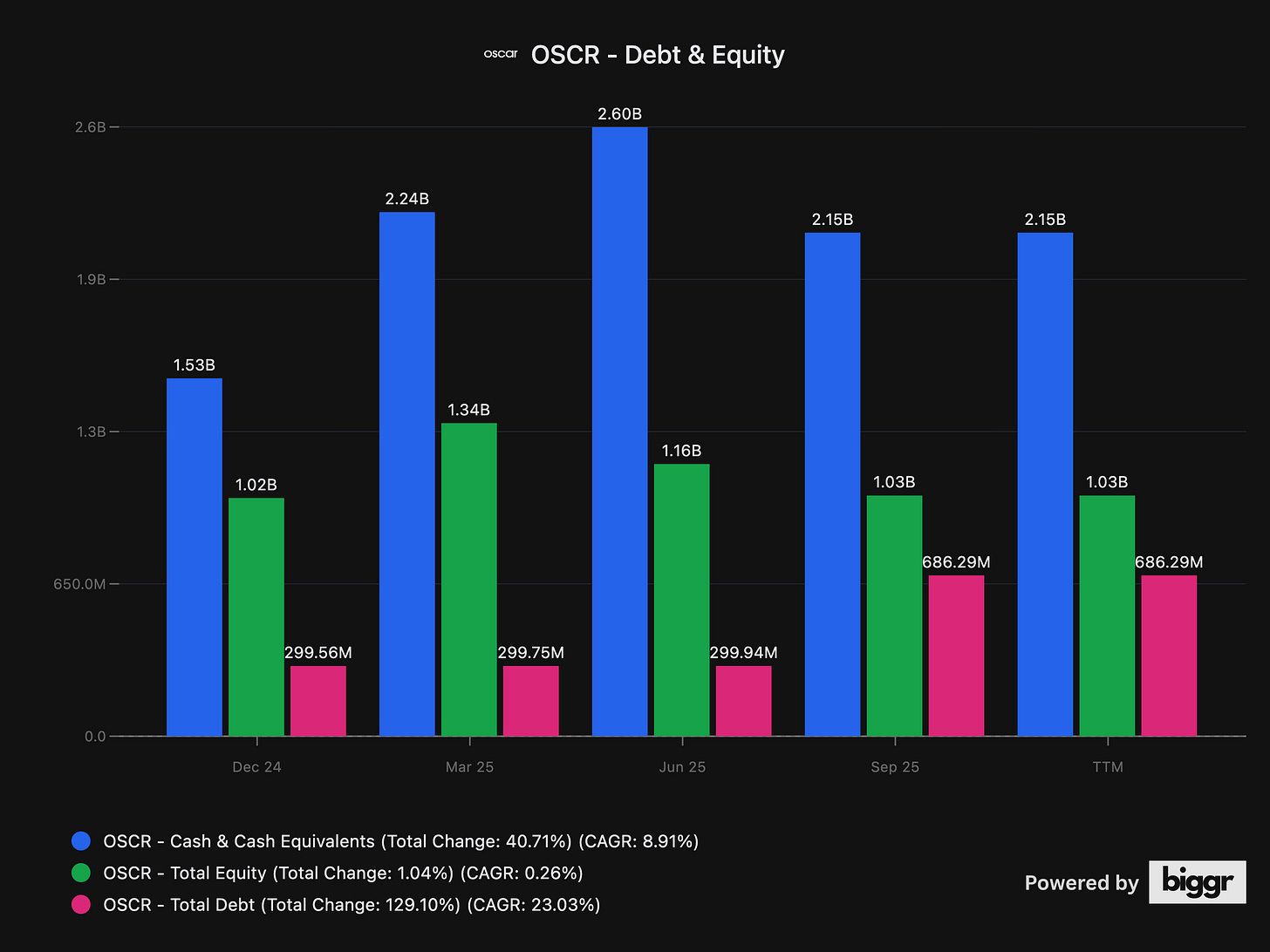

In short, business performance is nothing short of impressive. Yet, it gets even better when we turn to its balance sheet. It’s rock solid.

Oscar has just $686 million in debt against $1.03 billion of equity.

What I want to emphasize is its cash position; it’s giant. As of Q3 2025, Oscar’s insurance subsidiary had statutory capital+surplus of $1.2 billion, sitting nearly $600 million above the statutory minimum.

This means that Oscar can ask state insurance commissioners to free up some of this money as an extraordinary dividend to the parent, and then it can use it to propel growth.

This means that there are still ample opportunities available to Oscar to further enhance its already incredible performance.

In short, we are looking at an exceptional performance, strong competitive edge, and rock-solid balance sheet. This is a rare combination, and investing in such a combination at attractive prices generally pays off.

➡️ Investment Thesis

Now, let’s put what we have into perspective.

We have a company that entered into a regulated, competitive, and harsh market and has become not just one of the incumbents but also one of the leaders in just 10 years.

Its tech-driven model allows it to control morbidity and boost customer satisfaction, which leads to lower MLR, higher satisfaction, and retention. It passes some of its cost savings to members by offering lower prices than competitors, propelling its growth.

In short, it successfully competes pre-acquisition and retains post-acquisition.

When such a strong business in a barriered industry meets with a large addressable market, it’s not hard to forecast decades of above-average growth.

We have that element too. The addressable market is giant:

We now have just over 25 million enrollees in ACA, meaning there are another 95 million people who can tap into the individual marketplaces.

So, it’s not hard to see Oscar continuing to grow strongly and also achieve sustainable profitability as MLR trends normalize.

The CEO, Mark Bertolini, set out the investment thesis for us.

In an interview, he said: “In the health insurance industry, 2.5% net margin gets 0.5x sales multiple while 5% gets 1x sales. This year (2025), we are going to achieve around $11 billion in premium and a 2.5% net margin. Next year (2026), we will do $12 billion in premiums and achieve 5% net margin.”

So, they missed on 2.5% net margin this year but passed $11 billion in revenue, and they’ll likely finish the year somewhere around $12 billion.

So, even assuming no top-line growth, they can get $6 billion market cap next year with a 2.5% margin if MLR normalizes. This implies a 35% higher stock price as it’s valued at around $4.4 billion now.

If they achieve 5% margin as originally aimed by Bertolini, the stock can nearly triple as they can get a 1x sales multiple.

After each scenario, we can assume we’ll keep getting above-market returns for years, as there’ll still be a massive TAM to grow into. It can easily drive +10% annual growth for a very long time, combined with price increases and further potential for margin expansion due to AI-driven efficiencies.

On the surface, it’s as simple as this, but there is an elephant in the room—potential expiration of enhanced ACA subsidies.

How such an expiration could affect the business is a big question.

So, let’s now talk about the elephant in the room.

Potential Effects of ACA Subsidy Expiration

Here is the elephant in the room—ACA enrollments were stagnant before the implementation of enhanced subsidies.

In 2015, there were 11.7 million ACA enrollees, and it was only 12 million in early 2021, an increase of just 300K people in 6 long years.

The Government implemented enhanced subsidies in 2021 to help people grapple with the skyrocketing costs in the COVID-19 economy. ACA enrollments took off only after that, reaching 24 million in just 3 years.

This is how consequential enhanced subsidies were in spreading ACA enrollment. This means that they still found ACA plans unaffordable before enhanced subsidies.

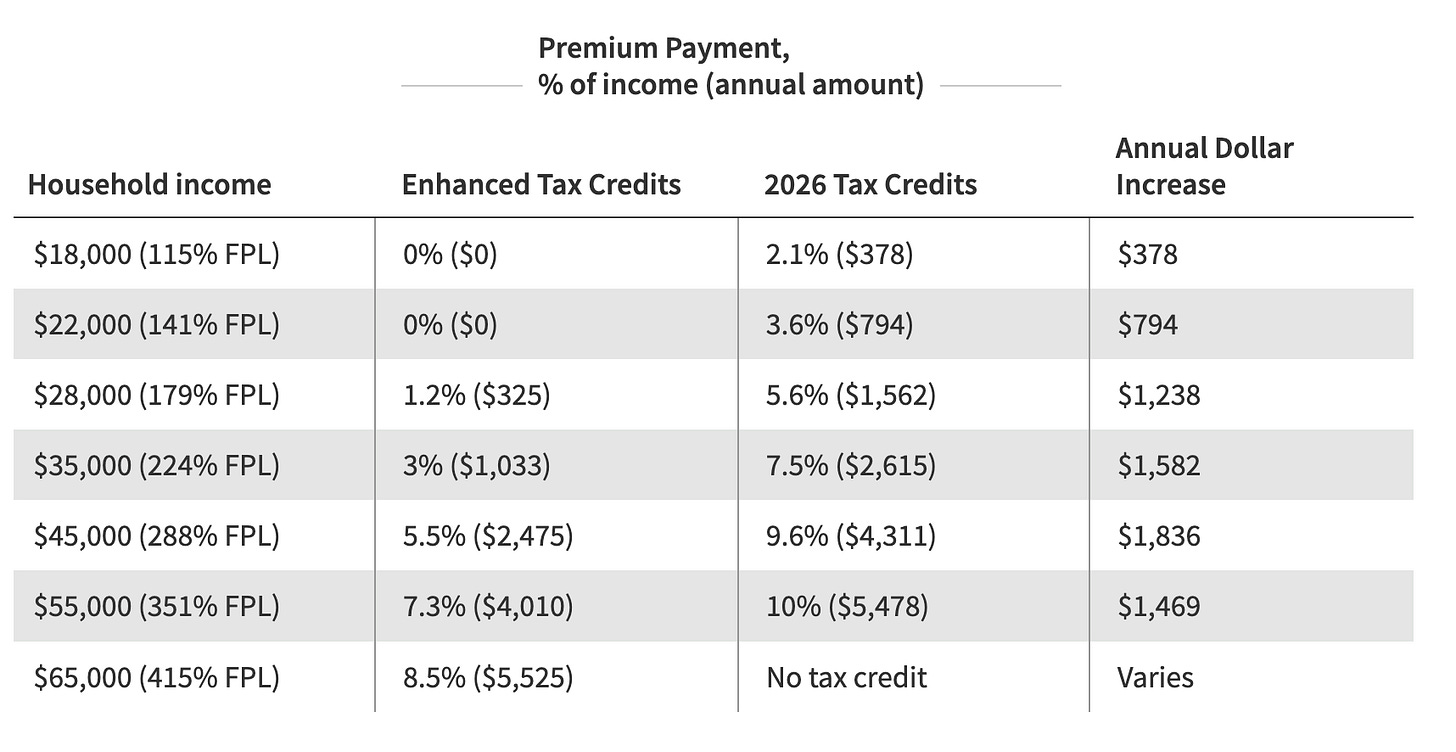

We can easily see this by looking at how much premiums are set to increase without enhanced subsidies:

Currently, 90% of the enrollees are benefiting from enhanced subsidies, and half of all ACA enrollees literally pay nothing out of pocket. These are people in the lowest income bracket; they make less than $22,000 a year.

If the subsidies expire, annual premium payments will go up, on average, by 114%. This will put a significant strain on the budgets that are already extremely tight.

So, what could be the effect on Oscar’s business?

Well, ACA is Oscar’s only business. Individual or employee-sponsored doesn’t matter; all the plans are sold through ACA marketplaces. Thus, Oscar will take its proportional hit if enhanced subsidies expire.

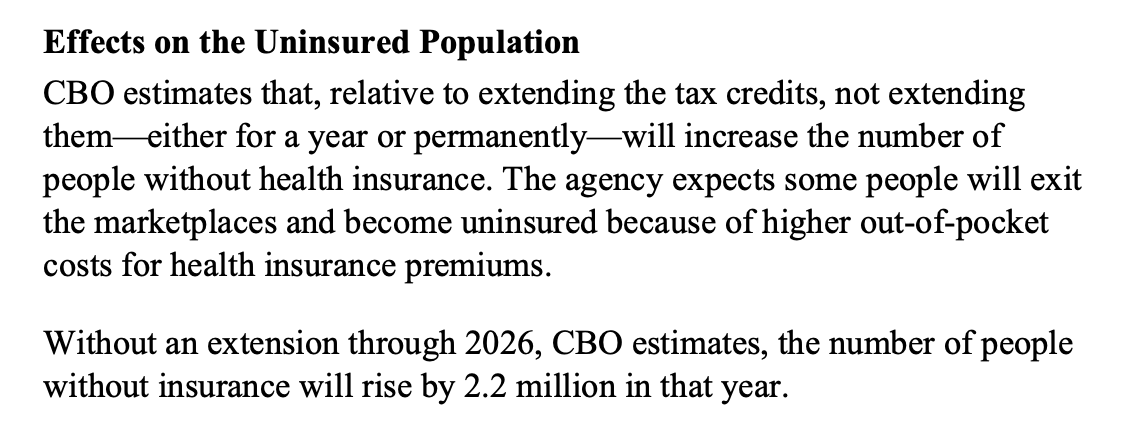

Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that around 2.2 million people can lose coverage in 2026 without subsidy extension, this is nearly 10% of all enrollees.

However, there are some other estimates substantially higher. Kaiser Family Foundation research foresees up to 30% of people losing coverage.

To be safe, I will take the midpoint and assume 20% of people will lose coverage.

Given that Oscar is a major player with nearly 10% market share in the industry, I assume it’ll take its full fair share and lose around 20% of its member base for this.

However, this doesn’t mean that the business will shrink by 20%.

There are offsetting factors.

First is, of course, organic growth. If the environment were stable, we would easily say that the business added new members in 2026. It’ll still add some new members in 2026 even if subsidies expire.

I can conservatively assume this would be around at least 10% as it grew its members by 25% last year. Now that plans will be more expensive if subsidies expire, we can safely project an organic member growth of around 5%.

The second offsetting factor is price increases.

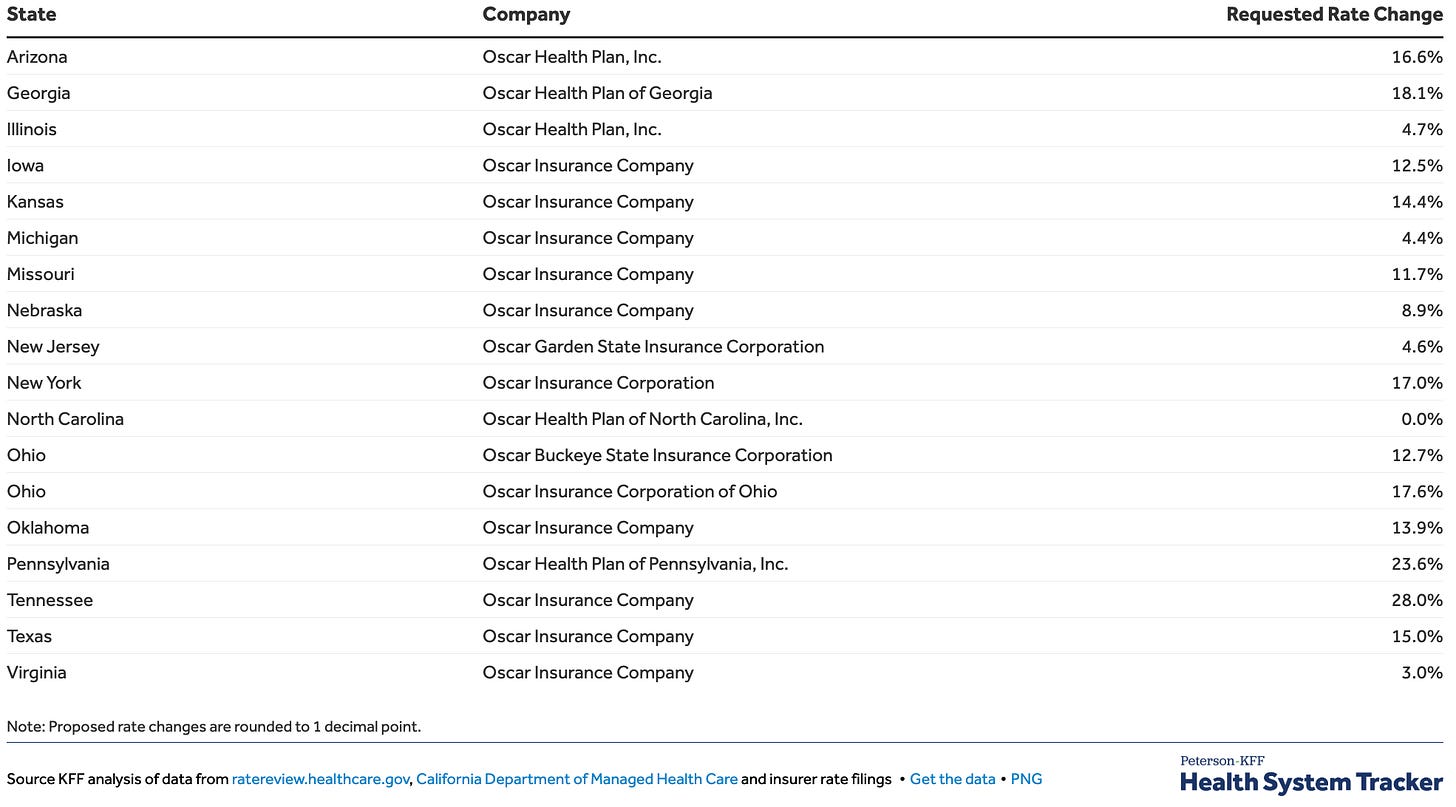

Oscar always knew that enhanced subsidies could expire at the end of this year. This is why I think they reflected this possibility in their proposed price increase back in August. They were proposing, on average, a 16-18% price increase:

Now, on top of that, we have experienced an unexpectedly high morbidity rate for the rest of 2025, and they have decided to refile their price increases.

In the Q3 earnings call, CEO Mark Bertolini said they filed for, on average, a 28% price increase in almost all marketplaces.

I suspect that increase wasn’t driven just by increasing morbidity but also by increased expectation as to the expiration of the subsidies. So, I think their pricing is now capable of mitigating more of the potential losses if enhanced subsidies expire.

This is the landscape we are looking at for Oscar.

It’s complicated. The opportunity looks very attractive, but significant risks also exist.

So, what should we do?

Valuation & Strategy

I’ll now create different scenarios for the expiration and extension of subsidies, value them, and calculate the option value of the stock today.

Then, I’ll explain the portfolio strategy for Oscar, i.e, what should be your average price, allocation, and what I am doing with my position.

Let’s start with the expiration scenario.