How To Think About Moats in The 21st Century?

In today's economy, slight competitive advantages can function like giant moats in some cases. These are where the the most asymmetric opportunities exist.

I think it’s now been very well known to many investors that the key to consistently generating above-average returns can be reduced to a three-pronged strategy:

Buy companies with durable competitive advantages, i.e, moats.

Don’t overpay for anything, regardless of the quality.

Do nothing; wait for the strategy to play out.

Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger established this concept so well that you’ll see it coming up over and over again in talks and the strategies of the successful investors of our time.

For instance, Terry Smith’s Fundsmith includes these three principles in its logo:

Though there are three ingredients, there is actually one critical decision to make—whether the company is a good one, i.e, whether it has a moat.

This is because the latter two steps are fairly easy after you get the first one right.

Companies with moats have predictable earnings, so it’s easy to value them. Doing nothing is also straightforward, and it’s a psychological process, not financial or business-related.

So, the linchpin of consistent outperformance is buying companies with moats.

The problem with this strategy is that companies with wide moats are generally overvalued, as their virtues are well-known and accepted by the majority of investors.

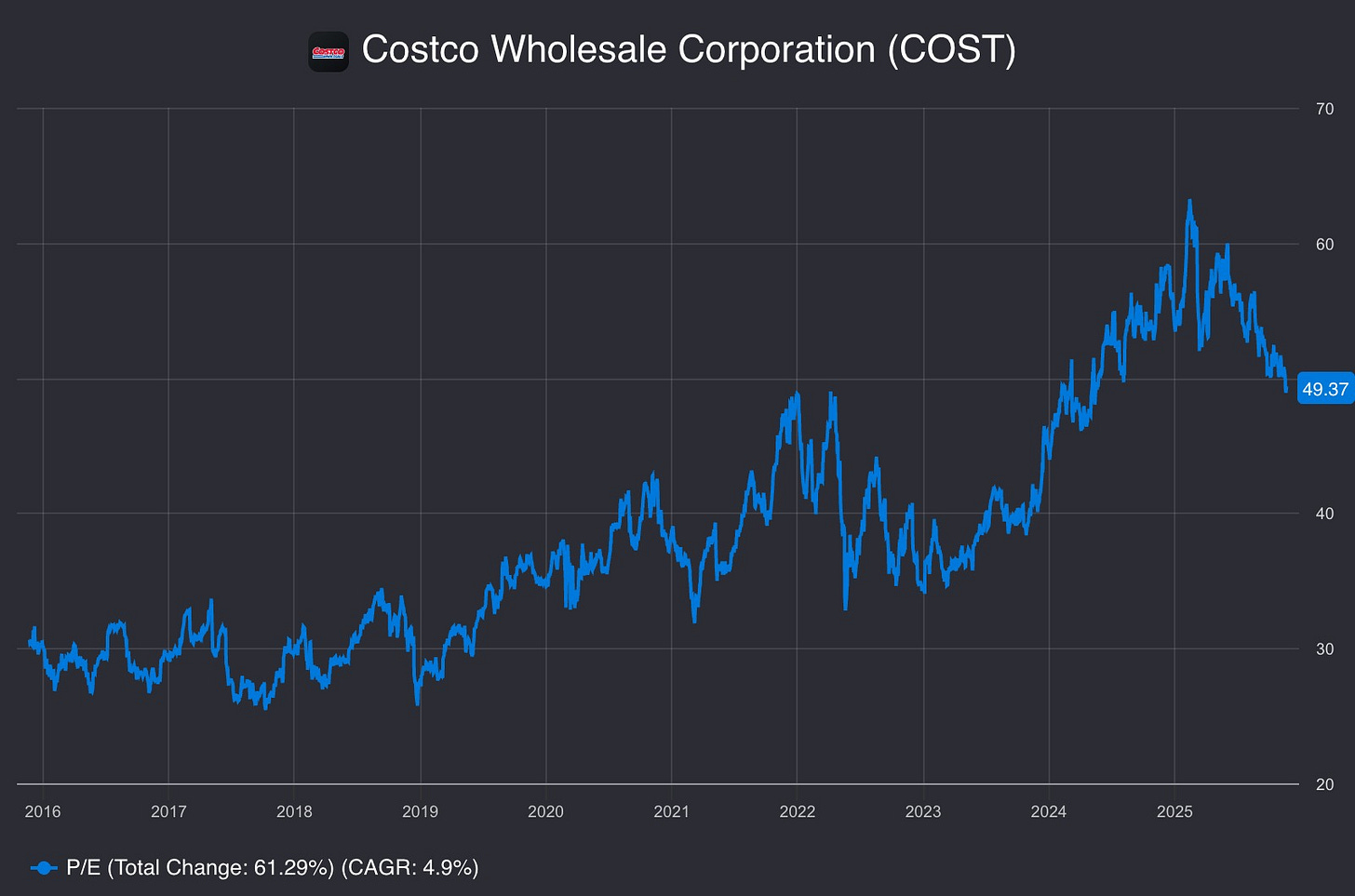

How many times could you have bought Costco at attractive prices in the last 10 years? It never traded below 25x earnings in this period:

Look at the other companies with well-known moats, and you’ll see a similar picture. In short, the strategy works, but opportunities to implement it are rare.

So, what should we do? Should we just wait for those moments and sit on cash until then? No, that would be pretty unproductive, as there is no guarantee that an opportunity would come. If you decided to buy Costco below 20x earnings in late 2016, you still haven’t gotten a single opportunity by now.

Luckily, the essence of moats has changed in today’s economy, and many investors haven’t adjusted their perspective. If you understand this, you can get ahead of others and exploit the opportunities they don’t even see.

This is similar to when some investors recognized that a digital business at 25x P/E could be cheap, since expensing intangible investment depresses earnings and artificially inflates P/E ratios. Those investors bought great businesses at attractive valuations, while traditional-minded investors ignored them as overvalued.

Today, I’ll try to explain how the concept of “moat” changed in the digital economy.

I’ll briefly revisit the classical moat theory and provide a perspective on the essence of the moat. Then I’ll try to explain why the moat in the 21st century is different from that in the 20th century.

Let’s dive in.

What Really Is A Moat?

Many things have been written about the concept. However, most of them focus on in what ways a moat can manifest itself, i.e, how to find companies with moats.

These write-ups generally draw on some forms of moats that have already been identified and create recipes or checklists based on their differentiating properties.

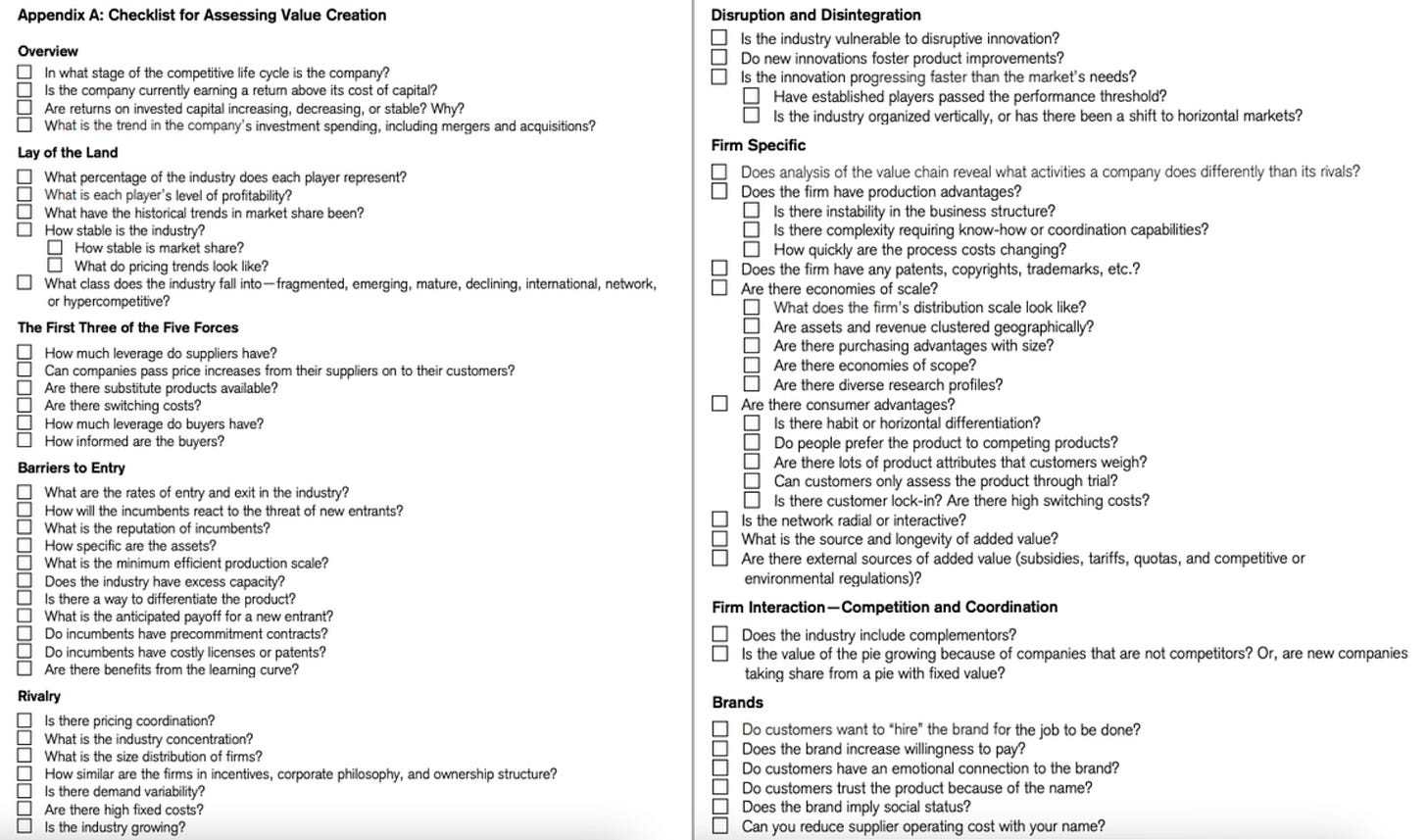

For me, the best one of such write-ups is Michael Mauboussin’s “Measuring The Moat”.

Here is the checklist attached to his survey:

There are three problems I have with such checklists:

They are static unless the writer revisits them regularly.

They are known to everybody, so they don’t give you an edge over others.

They are more tactical than strategic; they don’t give you the essence of the topic.

People who understand and follow those checklists likely do better than those who don’t, but you don’t have any advantage over others who also follow the checklist. This is incompatible with the very essence of investing, as you don’t make money in the market even when you are right if others are also right.

What gives you the advantage is understanding the essence of things, so you can identify the situations that don’t appear on the checklist but carry the essence of the topic. You see a moat where others don’t, and you make a bank if you are right.

So, let’s take a step back and identify the essence of the “moat.”

As is the case for many other investing concepts, I think Buffett provides the simplest and most comprehensive definition of moat:

What Buffett means when he talks about a moat is a “durable competitive advantage.”

Everything could be a competitive advantage in terms of enhancing a product’s chance to become a customer choice, like a bit better design, a bit cheaper price, a bit better service. Thus, in theory, there may be infinite sources of competitive advantage.

However, decades of observation have taught us that most advantages are ephemeral, and the list of advantages that can be made durable is a pretty short one. For instance, better design or a better service has never translated to a durable competitive advantage, as somebody eventually comes up with a better design or provides a better service.

Since the modern corporations emerged in the last century and the world started to globalize post World War II, the industrial organization and management literature has shown how otherwise ephemeral competitive edges can turn into a durable competitive advantage.

The most straightforward of them is price, as it’s one of the most studied competitive advantages.

The interesting thing is that it almost always starts as an ephemeral advantage. What generally happens is that one of the suppliers decides to sell at lower prices, shrinking their margins to sell more than the competitors. However, there’ll always be somebody who’ll accept lower margins.

Thus, for the price advantage to become durable, it needs to go beyond accepting lower margins. A company should be able to cut prices to the levels that would be uneconomical for competitors to match.

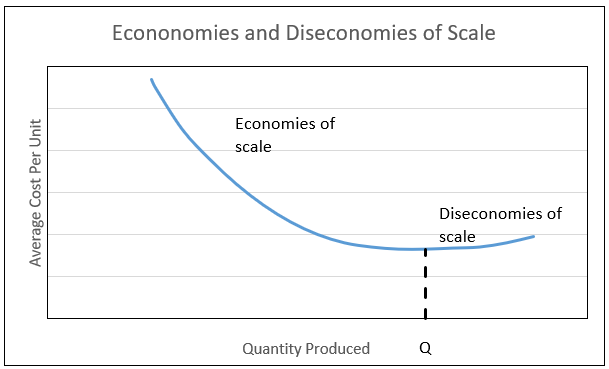

Achieving this goes through scaling the output beyond competitors. This is because the cost per output drops with the scale as fixed costs disperse over larger quantities:

This advantage accumulates through all operations of the business:

Its input cost per unit is lower due to a larger quantity of orders.

SG&A expenses per unit are lower.

Logistics cost per unit is lower.

As a result, the company with a greater scale has a lower cost than a smaller competitor at the same profit margin. Thus, a smaller competitor can never undercut the larger one, as it’ll always have a higher price at the same margin profile.

Scale advantage self-perpetuates as lower prices attract more customers, which results in even larger scale and lower prices. This way, an ephemeral advantage initially gained by cutting margins can turn into a durable competitive advantage.

If I had to say low-cost supplier is the most common durable competitive advantage. There are two others that I think are pretty pronounced:

Network effects

Brand power

These two again start as ephemeral.

A slightly bigger network has a competitive advantage over smaller ones, but it compounds over time. For instance, a prospective social media user would pick Instagram over others as they would find many more friends and activity there than on a small local app. This also self-perpetuates as a bigger network attracts more users, and more users result in an even bigger network.

Same for the brand power. Imagine that a well-known brand enters a market together with a lesser-known brand. A well-known brand has a higher chance of success, all else being equal. If it wins that market, it becomes an even stronger brand, and its chance of winning the next market also increases. It self-perpetuates.

There are others like these, but the essence is simple: Anything can be an advantage, but only a few of them can be made durable by some mechanism. Whatever the mechanism is, the advantage itself needs two properties to be able to become durable:

It should scale.

It should self-perpetuate to some degree.

What naturally flows from this is that being vaguely “better” doesn’t become durable, as it neither scales nor self-perpetuates. This is perhaps the most consequential finding of the competition theory, and it’s obviously true.

The best pizza in the world is made by some obscure dad & son pizzeria in Italy, but only a few people know the place, and even they don’t know it’s the best in the world; Domino’s, on the other hand, makes a shitty pizza, but everybody knows it. Domino’s has the brand, it scales, and self-perpetuates.

In short, what we have learnt from 100 years of modern, industrial economy is that anything can be a competitive advantage, but only a few of them can be made durable, and simply being better doesn’t count. This is what our understanding of moats, competitive analyses, and checklists has been based on.

It has worked up until now, but it’s changing, and you need to understand how if you want to get ahead of others.

Moat in the 21st Century

“Being better doesn’t count” was the strongest message of the business & management literature in the last century. There are many different views on what counts, but there is a unanimity that being better doesn’t count.

This century, the message will change: Being better can produce a durable competitive advantage.

You have to be careful here; it doesn’t say being better is a competitive advantage, it says being better can produce it.

To understand this, you have to understand one consequential distinction:

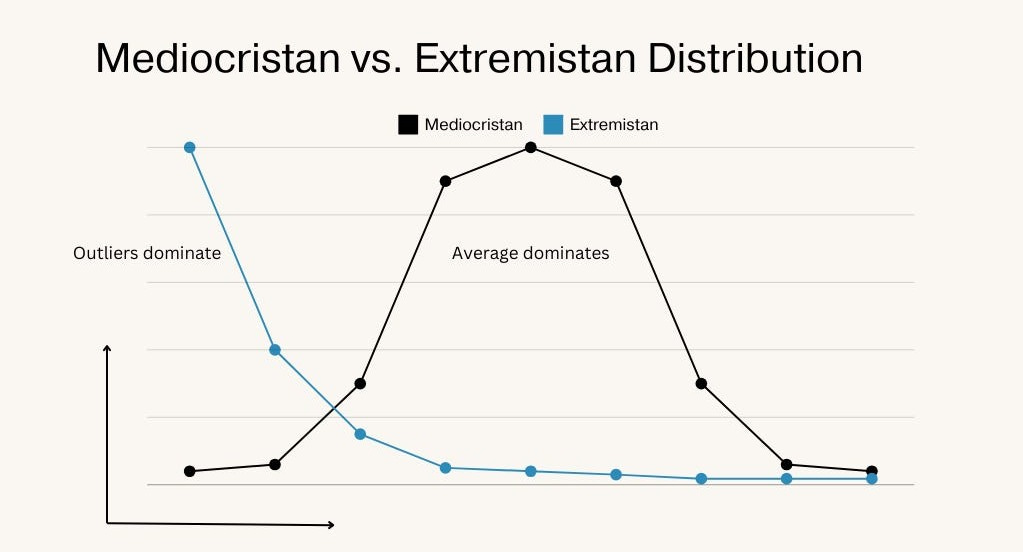

Mediocristan vs extremistan distribution.

What the hell do they mean?

Mediocristan refers to domains of small and inconsequential variations from the norm. No single event greatly skews the overall outcome. In contrast, extremistan is the domain of disproportionate extremes, where one outlier can dominate everything.

Think about weight. Measure the weight of 50,000 people in a stadium, and you won’t find that a single one of them makes up 10% of the aggregate weight of all. Most you’ll find will be something like 3/50,000 or 0.006%. Even the most extreme deviation from the norm will be small in absolute terms, and most people will be around the average weight. Averages dominate in mediocristan.

Wealth, on the other hand, is different. Look at those same people in the stadium. 49,999 of them may have an average wealth of $100,000, but the average wealth of the stadium will be $14 million if the last person you have is Elon Musk. He’ll alone make up 0.99290794% of all the wealth in the stadium. Outliers dominate in extremistan.

As a rule of thumb, physical things are of mediocristan while intangible things are of extremistan. The tallest building in a city can be 2x, 3x, 5x, or even 10x of the average height, but it won’t be 100,000x. Fame, on the other hand, is extremistan. Brad Pitt is infinitely more famous than an average male.

This is of profound importance for us because the global economy has shifted from a mediocristan land to an extremistan one in the last two decades.

The industrial economy of the 20th century was predominantly physical. It relied on sales of physical items. Thus, the character of the economy was mediocristan. This is because the customer's choice was limited by physical boundaries.

If you didn’t have Walmart in your town, low prices at Walmart in the neighbouring state would be irrelevant for you, as you wouldn’t cross states to shop for groceries. You would pick the cheapest store available to you. In other words, the tournament between the alternatives was limited by physical boundaries.

The restaurant business is a clear example of this.

Though the palate of Americans doesn’t change much state by state, the most popular fast-food chain by state varies:

In-N-Out may have better burgers than McDonald’s, but it’s irrelevant for somebody living in New York. Tournament effect is capped by the physical boundaries.

The same thing applied to the delivery of services, too. For instance, you needed to have a physical branch of a bank to open an account in 1990, even in the early 2000s. Your choice was limited by the banks you had in your city. The fact that there was a better bank somewhere across the country was irrelevant to you.

We can clearly see the effect of the mediocristan on sales data.

McDonald’s is the largest global restaurant chain in the world. It generated $26 billion in sales in the last twelve months. In the same period, global restaurant sales hit $4 trillion. McDonald’s, the largest restaurant chain in the world, makes up only 0.65% of all sales.

In contrast, the economy of the 21st century is increasingly digital. Goods and services that are delivered online are dominating the economy. Digital is the land of extremistan, as the tournament effect isn’t capped by the physical boundaries.

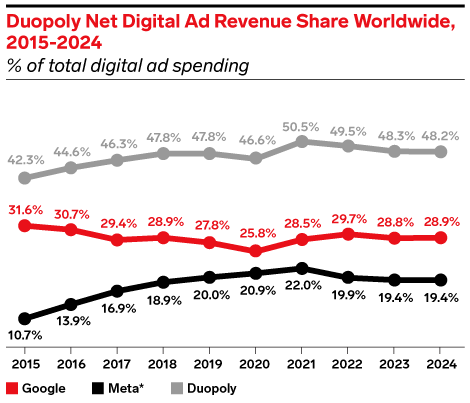

As of the end of 2024, Google and Meta accounted for 48% of all digital advertising revenues worldwide:

Look at the software sales, and you’ll see a similar pattern. Microsoft accounted for over 10% of software sales worldwide.

Digital is of extremistan. Thus, small advantages matter as there is no cap on the tournament effect. There is nothing preventing people from picking a slightly better option. And given that people try to make the rational choice for themselves, most end up picking a slightly better option.

Investors today focus too much on the network effects that Google and Facebook enjoy, but they forget that these companies didn’t start with giant networks. They have grown into giant networks because they were slightly better than the alternatives in the first place. They have grown massively because there was nothing preventing people from picking the slightly better option.

It applies to almost all of the digital giants today. They all started with small advantages. Think about Spotify. What made it different from other music streaming services? It had a better frontend. That’s all. But in extremistan, these small advantages compound as everybody can pick the slightly better alternative.

Now, remember that I said that a slight advantage doesn’t automatically turn into a moat; it just enables companies to produce a moat.

If everybody can benefit equally strongly from being better at any time, it’s impossible to produce a moat. There has to be something that either makes being slightly better less important for the existing customers or makes it very hard for competitors to be better.

Let’s start with the latter point: Slight advantages may enable the company to raise barriers for competitors.

Netflix is a perfect example of this. It was slightly better than the competitors, so the market initially concentrated around Netflix. That early concentration allowed it to gain scale and spend more on content than the competitors. Over time, this compounded, and it has become very hard for competitors to compete with Netflix’s content library.

Indeed, as of 2020, Netflix had already more than doubled its closest competitor in content spend:

The same applies to Facebook and Google. Both of them built double-sided networks that reinforced their small early advantages. Facebook could try to monetize through subscriptions, or freemium, but instead, it chose advertising. The former couldn’t create a double-sided network; the latter could.

In the cases above, slight advantages allowed the companies to scale faster than their competitors, as there was no cap on the tournament effect. Then, they used their scale to reinforce their advantages, building sustainable moats and making life very hard for the competitors.

The other way that slight advantages in extremistan can result in a moat is the cases where the product itself is sticky by nature.

In such cases, no physical cap on the tournament effect leads to market concentration around a few players that are slightly better than the others. If the product is sticky, users don’t easily flow to newcomers, even if they are slightly better than the incumbents. You have more to gain by sticking than switching. Slightly better works for the early movers, but not for the late comers.

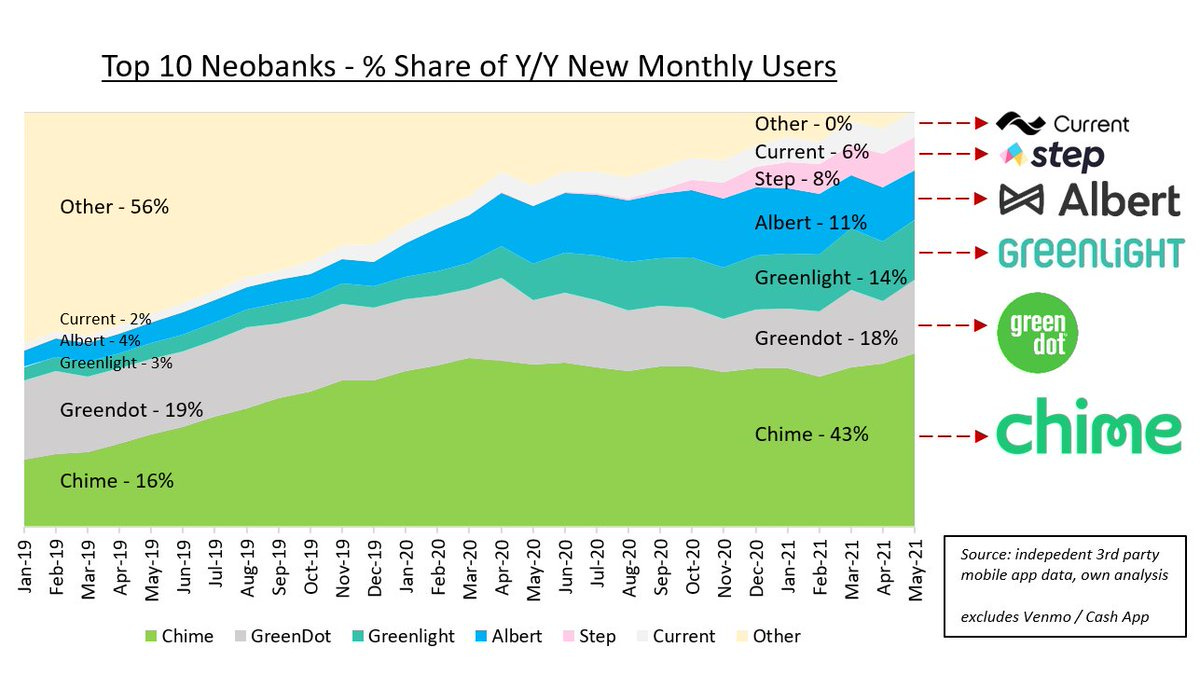

Neo-banks and insurtechs are examples.

Insurance is intrinsically sticky, as people pay lower premiums when they stick with their old providers. Plus, trust is an important factor in insurance. If you know that your insurer pays when you need it, switching to a different provider comes with an additional risk, as you don’t know how quickly it will pay claims. So, people generally don’t change their insurers even if an alternative provider is a few bucks cheaper.

Same for the banks. People tend to stick with their banks as they create a customer history in that bank. As a result, banks know old customers better and are more accommodating to their needs. It’s easier to get a loan from your old bank than from a new one. Thus, digital banks that had slight early advantages can gain disproportionately high market share, unlike traditional banking.

Chime was already dominating the neobanking in the United States with 43% market share as early as 2021:

In contrast, the largest traditional bank in the US is JPMorgan with over 12% market share. There are over 4,000 regional/community banks in the US, but there are only 74 neobanks.

In short, the economy has changed. In the physical, mediocristan economy of the 20th century, slight advantages weren’t attributed a big importance. They couldn’t create a moat. In contrast, in the digital, extremistan economy of the 21st century, small advantages can enable companies to create sustainable moats.

In the new economy, you shouldn’t rule out investing in digital businesses with slight advantages. They can end up gaining a disproportionately high share of the market, producing durable moats.

🏁 Final Words

The physical economy of the 20th century was mediocristan, so our understanding of competition and competitive advantages evolved based on it. In mediocristan, small advantages mean nothing as they don’t scale. The fact that a bit better burger chain exists in California doesn’t mean a thing for a customer in New York. Thus, we looked for definitive moats like brand power, patent protection, and unreplicable scale.

This is changing now.

The economy in the 21st century is increasingly digital, which is an extremistan domain. In extremistan, small advantages matter because they scale as there is nothing that prevents everybody from picking the slightly better product. No physical cap exists on the customer's choice. If Chime is a bit better in digital banking, customers from all 50 US states can pick it.

We only need to make sure that not everybody can equally benefit from being better. If a slightly better competitor can come up next year and there is nothing preventing people from switching to it, being better doesn’t mean a dime. However, if there are some switching barriers, then being a bit better can turn into a moat.

Switching barriers in extremistan generally exists in two ways:

A company translates the early advantage to a definitive one through scale, network effects, etc. Google, Facebook, Netflix, and Spotify are examples.

The product is intrinsically sticky. Banking and insurance are examples.

Understanding this can provide investors with an unfair competitive advantage, as our business and management literature is still largely living in the physical economy of the 20th century. Our understanding of the competition hasn’t fully adjusted to the digital economy of the 21st century.

Look at Walmart and NuBank, and you’ll see that the moat premium in the former is way larger than in the latter. People don’t see it. They are stuck in the moats of the last century.

Thus, if you understand how small advantages can translate to wide moats in extremistan, you can see great potential in companies ignored by others. A quick checklist would be:

Look at the industry, is it mediocristan or extemistan?

Is the product intrinsically sticky, or can it be made consistently better than the competitors due to scale, network effects, etc?

Does the company you are looking at have a small but obvious advantage over the competitors?

If you answer all these questions “yes”, then you are probably looking at a potential wide-moat company that likely hasn’t been given the wide-moat premium by the market yet. That is your opportunity.

Understand the new dynamics of the competition, and you’ll see the emerging moats faster than the market and be able to capitalize on them. This is the key to outperformance in the new economy.

That’s all friends!

Thanks for reading Capitalist-Letters!

Please share your thoughts in the comments below.

👋🏽👋🏽See you in the next issue!

Great work!

Thanks for this article about Mediocristan vs Extremistan in investing. Great introduction to Gaussian Distribution vs. Power Law Distribution. Let's see how stable companies from both groups will be in case of a bubble burst, if it happens in the foreseeable future. I think, and I adjust my portfolio accordingly, that companies with classic MOAT will experience a less significant decline in such a case.