Earnings Mania: Please Stop Listening To Noise!

A single earnings report rarely provides real and valuable signals, yet people can't stop obsessing over them.

I hate earnings seasons.

Now you may ask—how come you can hate earnings season as an investor?

Well, earnings seasons are like rock festivals.

There are only a few good groups worth listening to, and you only want to listen to specific songs of them. Yet, people around are euphoric, fueled by alcohol, and they take every single group and song with a scream (investors are very much like this).

It gives you a headache.

Earnings seasons are exactly like that for me.

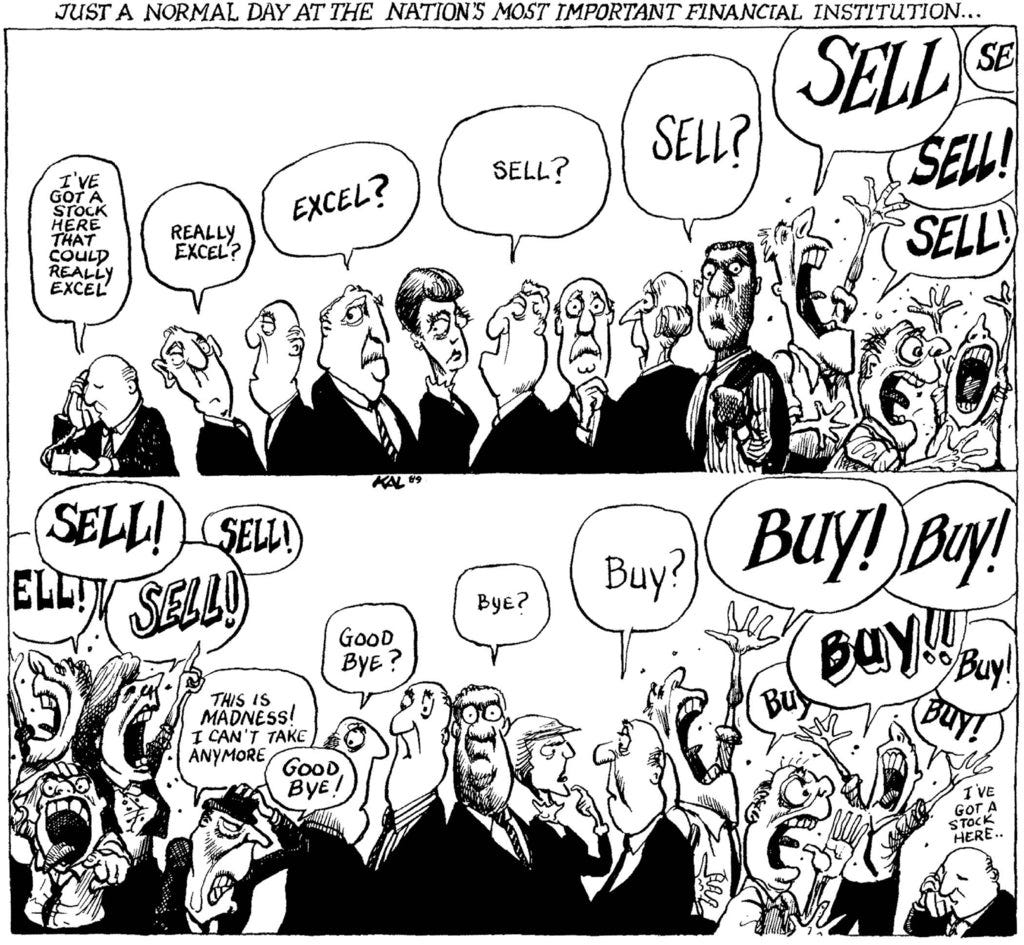

People wait for earnings to come out, and when they come out, instead of reading the reports themselves and thinking independently about what it means for their investment thesis, they look at the price action and rush to react as they see the price moving fast in real time.

They feel like they have to perceive what the release means as quickly as possible and react appropriately, or they’ll fall behind. This urge is especially powerful when the initial price reaction is negative.

And just like that, we have millions of investors screaming “buy” or “sell” after every earnings release, regardless of whether it deserves any reaction. It gives me a headache.

What’s worse is that, despite causing a significant headache, a single earnings report isn’t worth a dime 90% of the time. They tell you very little about the business and even less about how your long-term investment thesis is playing out.

Yet, we obsess over them.

We should stop doing that and return to sanity. This is what I’ll try to do today.

I’ll try to explain three things:

Why earnings reports aren’t worth a dime 90% of the dime?

How can you catch a real signal?

How to read earnings prints?

Let’s try getting some sanity.

A single earnings report isn’t worth a dime.

One of the things that perplexes me most is how investors come to treat companies like machines. The longer an investor is in the markets, the stronger this tendency is.

They see companies like machines and Wall Street expectations as signals validating the proper functioning of machines. If the targets aren’t hit, there should be something wrong with the machine.

This is obviously pure bullshit, and I can’t think of any reasonable people who could argue otherwise.

Businesses are organizations made up of humans. It takes time for them to grow, mature, and decline. And each phase isn’t linear in itself. There are always setbacks and booms. Just like we all have in our lives.

Thus, expecting a linear development quarter over quarter isn’t reasonable.

There can be many reasons for quarterly misses:

Recognition of significant revenue might have happened after the quarterly close.

The broader economy might have unpredictably slowed down.

The business might have botched the execution.

Let’s take the worst-sounding one, shall we? Let’s assume that a quarterly print came in badly because the business suffered a real setback.

What could that setback be? Assume that we are looking at a short-term lender, and the earnings print came in worse than expected because their risk models behaved overly permissively, leading to more than expected losses this quarter.

Here is the controversial thing—as an investor, you should love this kind of setback, not hate it, provided that it doesn’t kill the business.

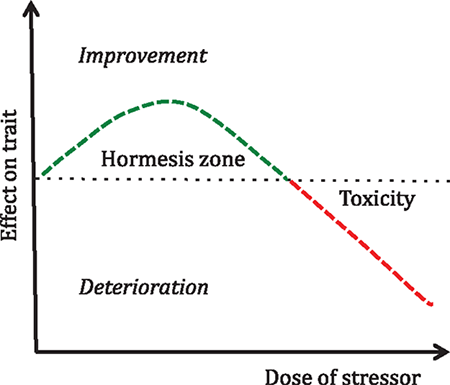

Why? It’s the old concept of antifragility.

Complex systems need stressors. For them, stress is information, more valuable information than that which could be gathered simply by observation and tinkering.

Adjusting the posture based on the new information makes the system stronger, not weaker.

Think about babies.

Pain is the primary way they gather information because their reasoning and thinking capabilities are not developed enough. Experiencing pain as a result of their own actions, provided that they aren’t dead, will improve their chances of survival as they’ll avoid the pain-giving event.

This is called hermosis. Complex systems can benefit from small harms, provided that they survive the harm. They become stronger.

Think about a baby who touches a hot pan and gets burned. That’s valuable information. He won’t try to grab a pan with his bare hands again. He just got stronger in the world.

We can adapt this to businesses as well because they are also complex systems.

If a lender suffers losses that don’t bankrupt it, it’ll likely become stronger in the long term as it’ll readjust its underwriting not to repeat the mistakes that led to losses.

Talking more generally, investors should be happy for the setbacks that don’t break the long-term thesis, as they likely lead to a long-term improvement.

This brings us to one important conclusion: Assuming that negative prints are suspects for important signals and a portion of those are actually desirable setbacks, only a small portion of negative prints are actually thesis-breaking signals.

That applies to positive prints as well. Just like not all negative prints are bad, not all positive prints are good.

Let’s continue the lender example for consistency.

The lender you are holding might have delivered a superior print, beating on top and the bottom line with accelerating growth and skyrocketing loan volumes due to lowering the lending standards. However, if you are seeing that we are going to a tighter monetary environment, that positive print is actually a bad signal.

The business exceeds expectations, but it now carries more of the higher-risk loans on the balance sheet. The positive print actually signalled a more fragile business. If the monetary environment tightens as you expect, it may be hammered down. You may consider exiting despite a positive print.

So, the question is—how can we tell a real signal-bearing earnings print from a simple occurrence?

Well, to start with, it’s very unlikely that a single earnings print carries an important signal. As said above, there may be many reasons for both booms and busts in the performance. Maybe the CEO was getting a divorce, and he wasn’t focused; you can’t know.

Even if there is a signal, it’s very unlikely that anybody can consistently anticipate the signal without having some pattern to look at. Most of these attempts will be vain speculations. The word “pattern” is the key here.

Signals don’t perish; if something is a real signal, they tend to persist, and the time required to draw patterns changes from one company to another.

The time required to conclude that an insurer’s business model is broken may require more than a year of results, as people buy insurance annually, and you need two annual prints or at least one annual and one quarterly print to see whether the problem may persist into the next year or not.

However, it may take only two quarters to conclude the declining loan quality of a lender that gives short-term, unsecured personal loans.

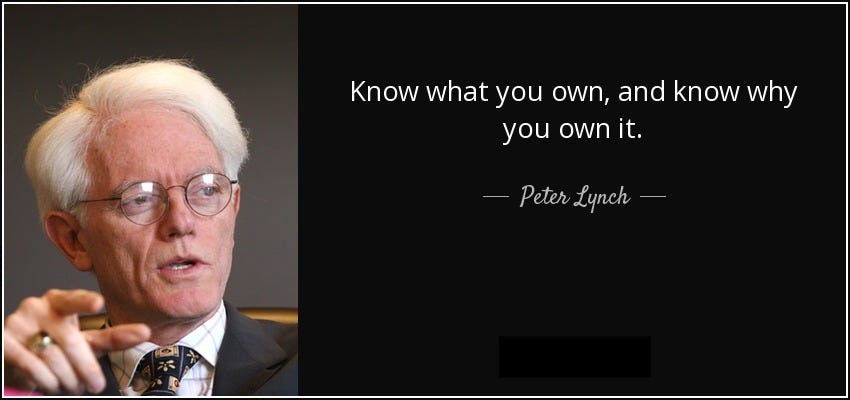

You have to understand the business.

You shouldn’t slam an insurer after a year of bad print, but you may well exit a lender after two prints of declining underwriting quality.

To be able to see what matters and in what period, you have to really understand and know the business.

It is imperative for you to be able to get the right signals from the business. It’s non-negotiable.

Let’s expand on this one.

How to catch a real signal from earnings reports?

There is a reason all the great investors emphasize that you should really know the business you own. Otherwise, you’ll always be a captive of what’s fed to you.

Unfortunately, most people don’t know their holdings enough to form their own opinions about the earnings reports.

What does it really mean to know the business?

Well, you have to understand what it does and how it does it, obviously. Who uses its service, how its service or product generates value, etc. What are the key performance indicators you can use to observe the development of its services and products?

The more you know about these, the better insight you develop about the business. And be careful here, I am not saying knowledge, it’s insight. It also includes a fair degree of intuition. Insight and intuition are closely linked cognitive processes that often work in tandem.

Intuition almost always precedes tangible knowledge. However, interestingly, the more you know about a topic, the better intuition you develop.

Let’s take Amazon as a simple example.

Anybody who has a fair degree of knowledge about a business knows that it’s mainly composed of three parts:

Commerce and related services (including logistics and ads)

Subscription services (things like Prime, Amazon Video, etc)

Amazon Web Services (its cash cow cloud business)

You know that AWS is what makes the stock move as it makes upthe bulk of net earnings.

Now, the more you know about this, its customers, and environment a better intuition you’ll develop about the business.

Here is an example.

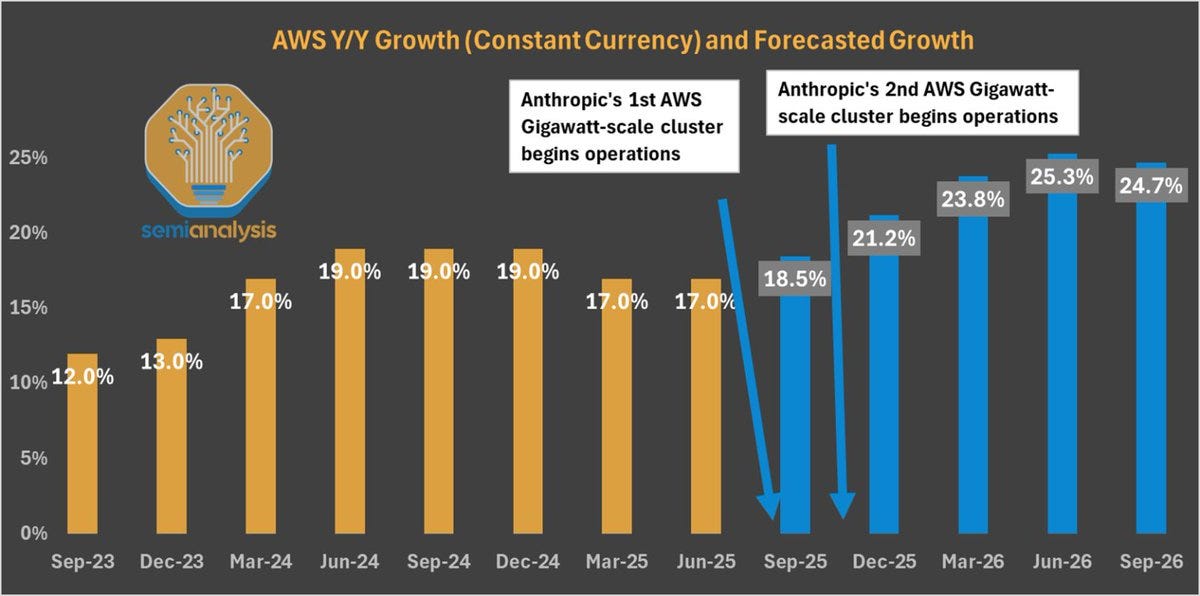

A person who knows that Amazon is the biggest private shareholder in Anthropic and AWS is the primary cloud partner for Anthropic would understand that Anthropic’s growth will substantially affect the performance of AWS.

If that person knew that Anthropic was growing skyrockets and their giga-watt scale AWS clusters were set to come online in the second half of 2025, he would expect a significant acceleration in AWS growth.

This is exactly what SemiAnalysis knew and wrote about; they have knowledge and intuition about the matter:

They forecasted AWS growth to accelerate in the second half of last year, and they were right. In Q3 and Q4 2025, AWS growth accelerated to 20% and 24,% respectively.

This is how knowledge on the matter and intuition that flows from the knowledge drives alpha.

Now, let’s take it a step further.

If you have tried AI models, especially coding agents, you’ll see that Anthropic’s Claude and Claude Code are undisputed. Their narrow focus on coding is paying off because enterprises are adopting AI for coding tasks faster than for other tasks.

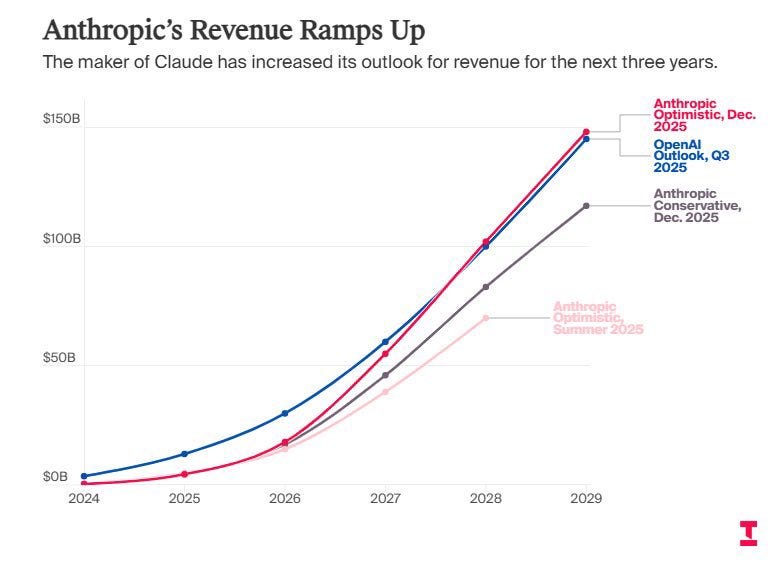

If you are a person who noticed this by himself after trying the models, you could think there is a possibility that Anthropic may grow way faster than OpenAI. You could just feel it a few months ago, and you would see last month that Anthropic is indeed guiding for faster growth than OpenAI:

Now imagine you are reading Amazon’s Q4 2025 earnings print with all this knowledge and intuition in mind.

Here are the things you know:

You know that Anthropic is growing skyrockets.

Amazon is also preparing to expand its partnership with OpenAI.

And in the earnings, they are telling you that they are doubling the capex.

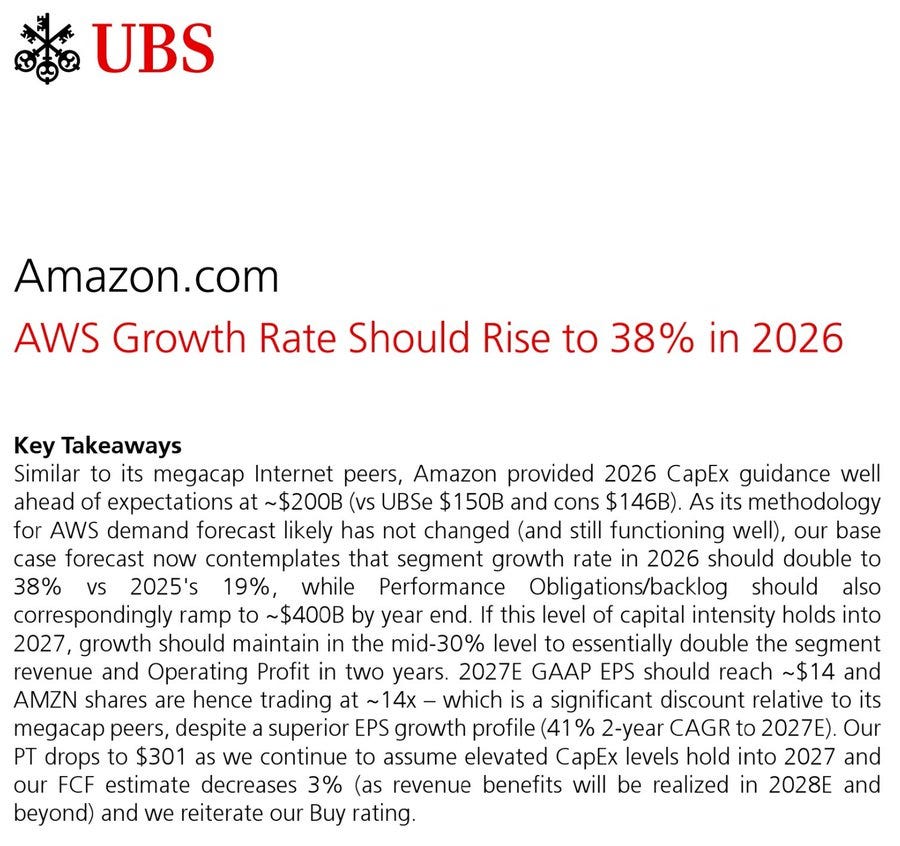

You could easily think that they can grow faster than what they recorded in the last quarter, 24%. If you know that Amazon has a massive ROI on cloud capex, you can revise your growth expectation without being concerned much about depreciation and rate the stock as “buy” rather than “hold” or “sell”.

Now, note that it’s only a matter of time before others in the market reach the same conclusion as you, because there are many people making money on a stock at any given time.

Here, in this case, UBS significantly revised its AWS growth expectation to 38%:

And note that the fact that the AWS growth accelerated in the last two quarters increases the likelihood that this is a real signal. If a business came out of nowhere and said that they were investing for growth, that would be way less valuable and less reliable a signal.

Now, let’s think about another example of how your knowledge of business and intuition may allow you to catch a real signal, this time a negative one.

This is actually a real event from my investing history, and the followers of this publication witnessed it in real time.

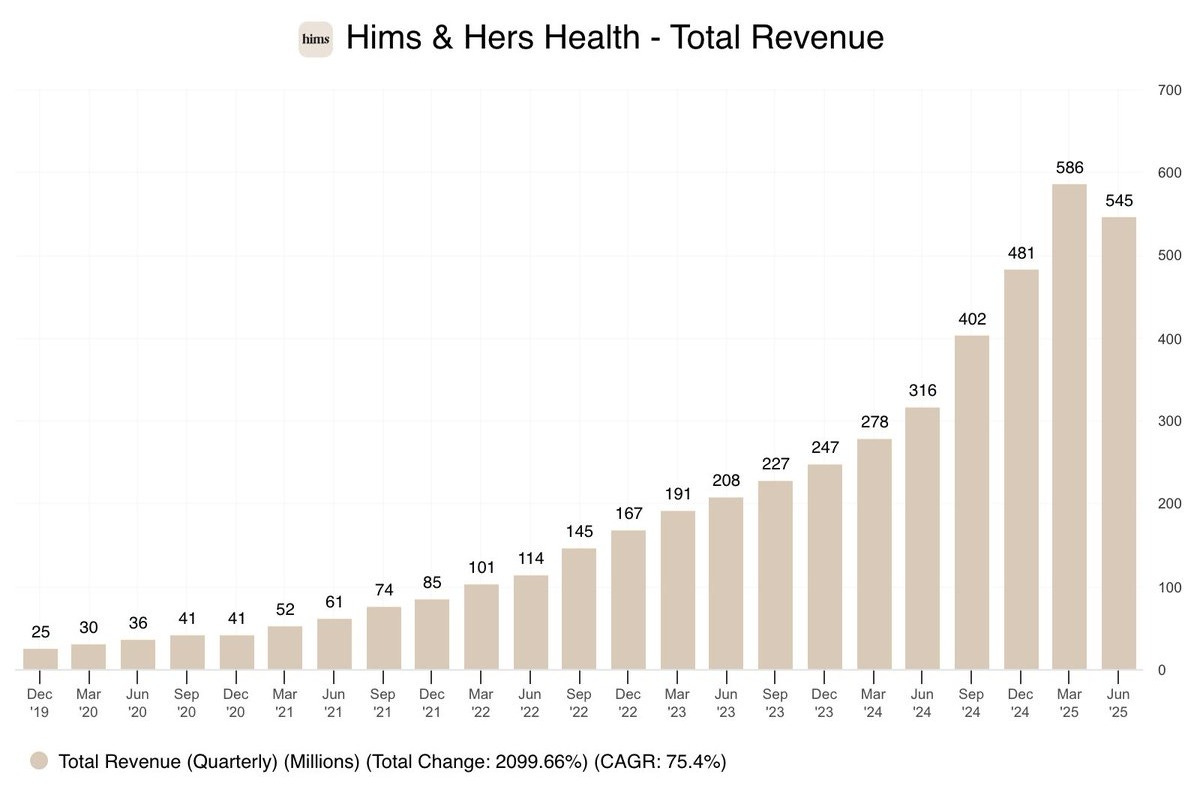

I was a very early bull for Hims & Hers.

I liked their execution and vision, plus the valuation was very attractive when I got into the stock in 2023. When I bought the stock, there was nothing about GLP-1s, so my thesis was focused mainly on the core business.

Then they started selling compounded semaglutide, as there was a shortage that allowed them to do compounding. Growth skyrocketed, but all their focus shifted to the semaglutide business. Wall Street followed, and suddenly GLP-1 became the main thing that moved the stock.

I openly said everywhere that I never liked this. I would prefer them to focus on the core and grow more slowly.

In Q1 2025, the FDA declared that the semaglutide shortage ended and gave some time to compounders to sell what they produced, but nothing more.

Hims & Hers announced they would follow the law and limit selling compounded semaglutide with a 503(A) exception under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which allows compounding if the drug requires personalization.

I was initially okay with this and expected them to focus on the core business and keep growing it. However, two earnings prints that followed made me pretty skeptical:

In Q1, Hims brought in $230 million in GLP-1 revenue, making up 39% of all revenues. In Q2, GLP-1 revenues were $190 million, again making up around 35% of all revenues.

Without GLP-1s, the core business growth would have declined to 15%. There was a possibility that they could reaccelerate the growth of the core business by shifting resources from GLP-1s to core, but at the time, they still looked very focused on somehow selling GLP-1s.

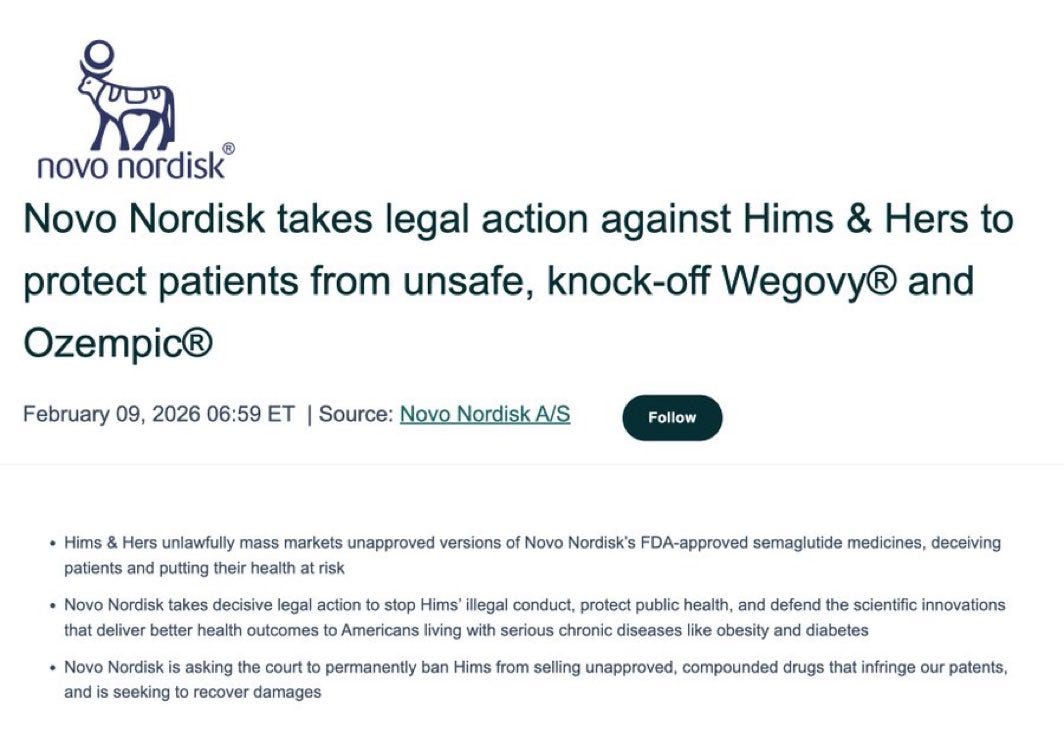

That put the business at risk. The rationale was simple. If they insisted on selling the compounded version of the drug, they would be sued at some point. If they were sued, it would distract them even more, and it would take a lot of time and effort get out of the muddy waters and turn the core business into fast growth.

The risk wasn’t worth the reward.

So, I exited just after their second quarter report, around $50 per share, locking in over 300% in gains.

Last week, Novo Nordisk announced that it would sue Hims:

If I didn’t develop this intuition about the business, I wouldn’t be disturbed by their business strategy, and I would keep the stock. I would look at the headline numbers and think that everything was alright.

And again, note that this signal went back to three-quarters. Q4 2024 told me that the revenue ramp could be at risk if they didn’t focus, but I needed more prints to see that they would not return to core. Q1 and Q2 2025 proved that they still wanted to pursue the GLP-1 market. I exited only after this.

Without building this broad knowledge of business and developing an intuition based on it, you won’t be able to read a valuable signal from earnings reports. You’ll be following the headline reports and what others are writing about it.

And again, keep in mind that it often takes more than a quarter to validate a signal, so any action you take on a single quarterly print will likely be more wrong than right.

How to read earnings with sanity?

Let’s assume you have developed significant knowledge of the business. This means that you know what to track. Let’s call them key performance indicators (KPIs).

What you want to do is to eliminate the noise. You shouldn’t care about how the market or other people are reacting to it.

Assuming that you are a serious investor, you should have created an investment thesis. You have to look at the developments in KPIs and try to understand what it means for your thesis.

For a simple company, KPIs may be as simple as revenue, margins, and earnings. However, for a, let’s say, lender, there’ll be factors like originations, markdowns, and delinquency rates.

You have to understand two things:

How is the business performing compared to your thesis?

Is the business going in the right direction considering your future expectations?

If your thesis was based on the business’s growing 8% a year, the sell-off due to delivering 9% growth but missing 11% expectation isn’t relevant for your thesis. You have to be able to say, “It’s irrelevant for my thesis, I already assumed 8% growth.”

Second, you must understand whether KPIs are developing in the direction you wanted.

As it’s one of the companies in my portfolio that recently announced earnings, let’s take Pagaya as an example.

It’s a second-look lending network that raises funds largely through asset-based securitizations and forward flow agreements, so the KPIs I care about are pretty straightforward:

Network volume

Revenue & income

Markdowns on securities carried on the balance sheet.

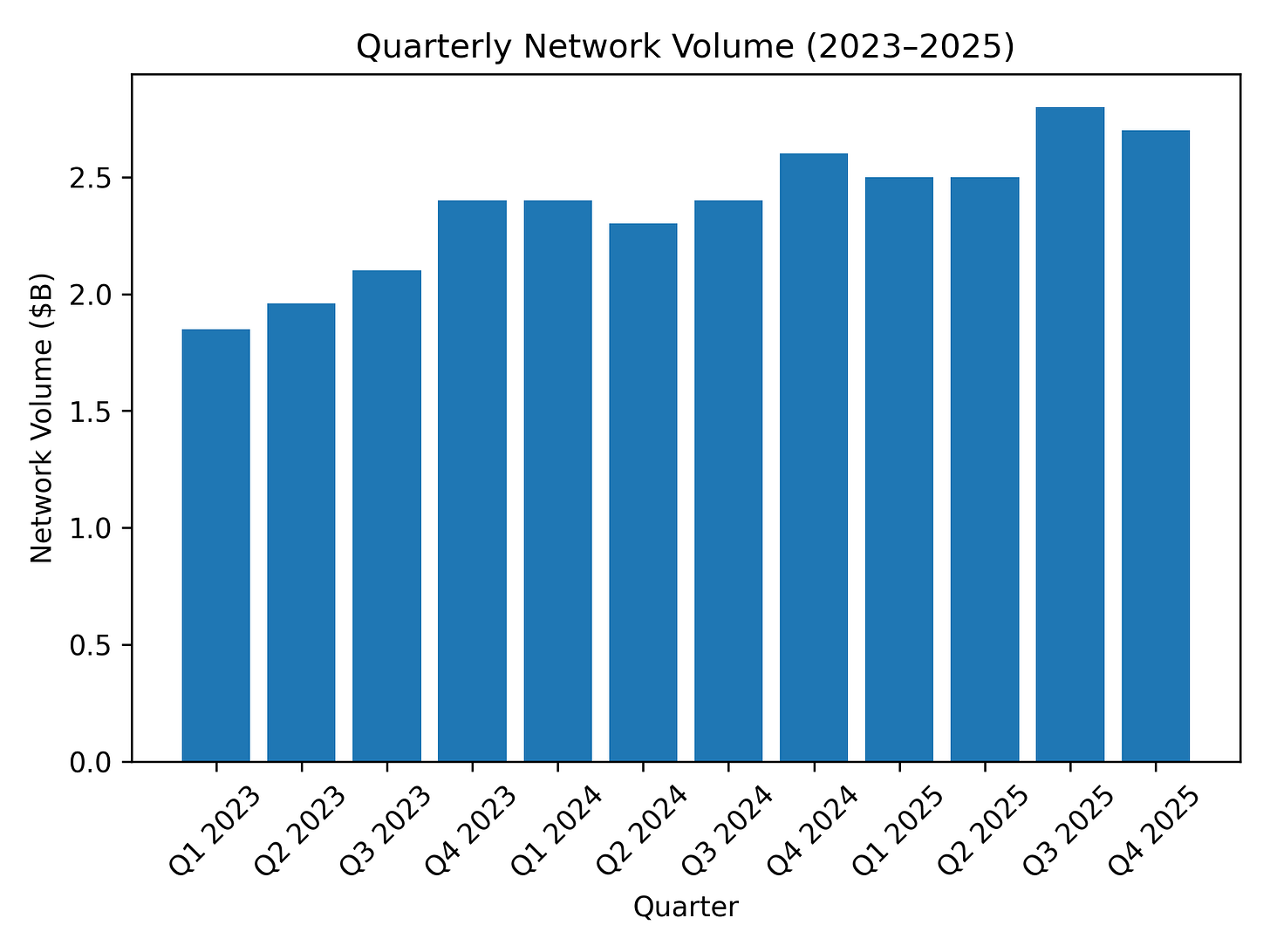

Let’s look at its network volume:

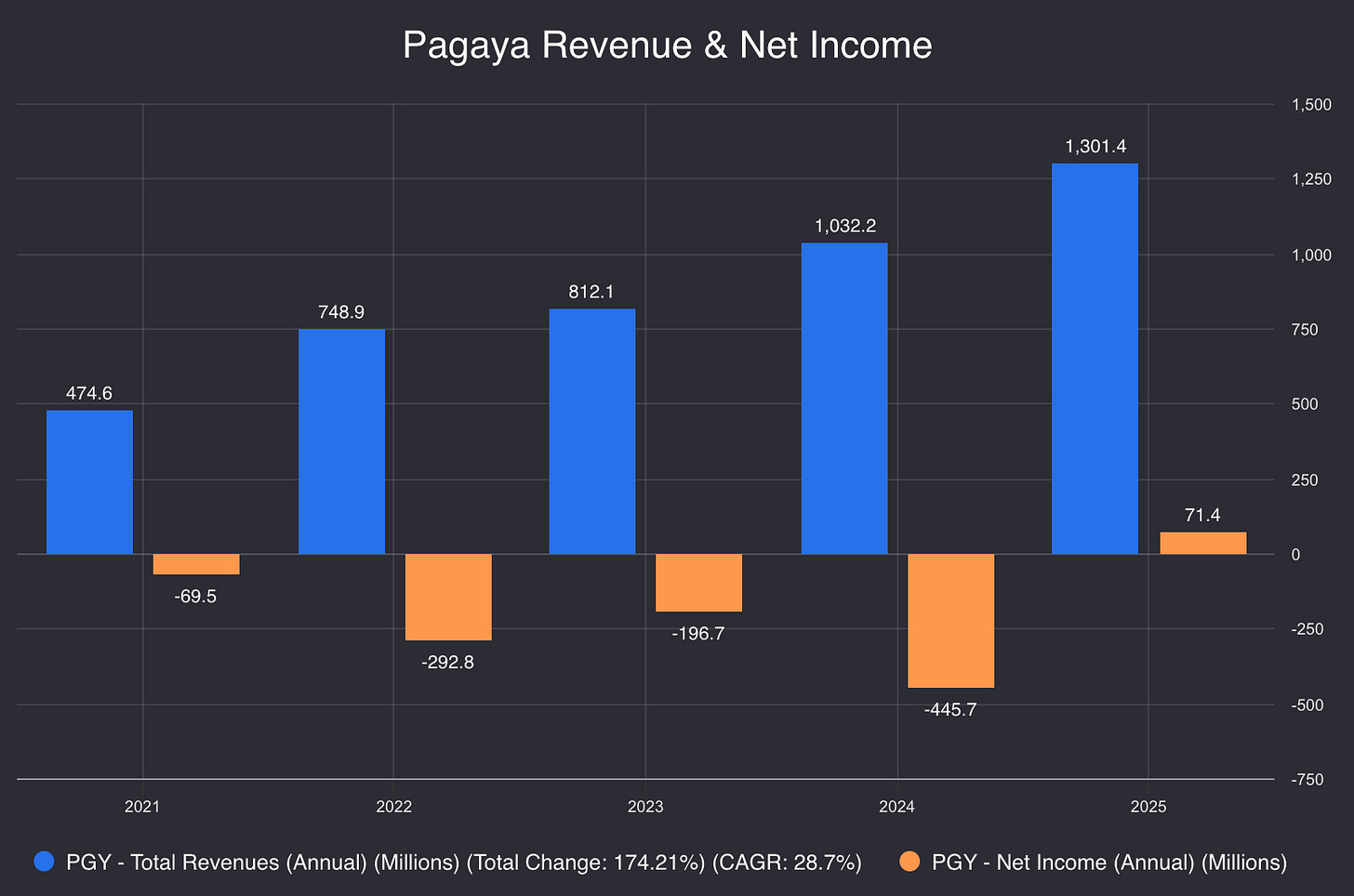

It’s showing a healthy growth on both a quarter-over-quarter basis since 2023 and moving in the right direction. Let’s turn to revenues and net income:

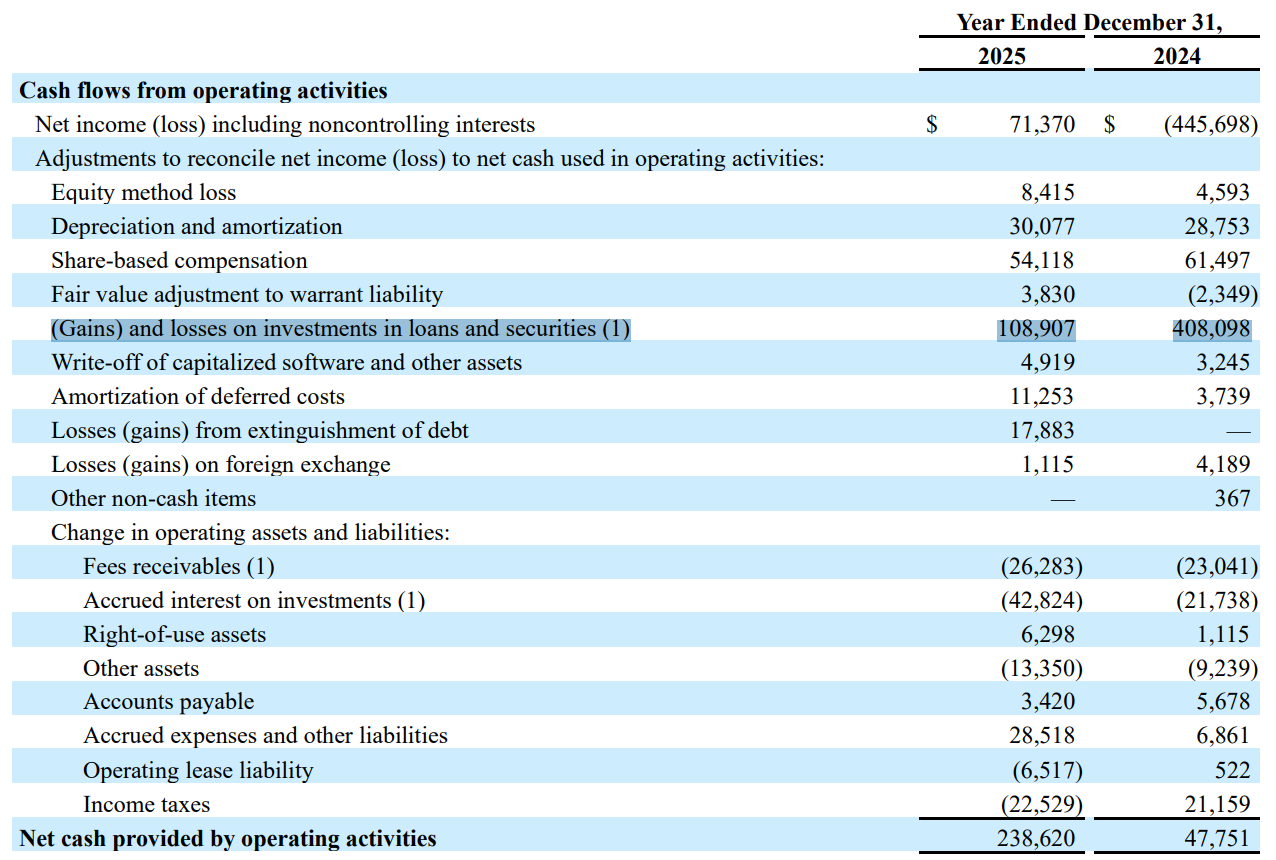

As you see, revenue has been ramping up following the growth in network volume. Earnings, on the other hand, are recovering after a disastrous 2024. What happened in 2024? This takes us to our next KPI, markdowns.

Last year, Pagaya’s markdowns, or you may say impairment loss on investments in loans and securities, jumped to $408 million in 2024, from just $135 million in 2023.

As an informed investor, you would like this number to decrease, as it is consuming Pagaya’s equity. Q4 print showed a significant normalization in markdowns, as they declined to $109 million for the full year 2025. All looks well.

We are clearly seeing the concept of hormesis at play here.

Pagaya drew lessons from its failures in 2024 and adjusted its business accordingly. As a result, its business is stronger now, as illustrated by the drastic decline in markdowns and flipping to profitability.

Now that you see the KPIs, you should try to understand how the business should position itself going forward. We are looking at a lending network, so monetary policy and macro conditions are of utmost importance.

When I look at the macro conditions ahead, I see significant uncertainty:

The effect of tariffs is hitting the economy with a lag.

Credit spread is at very low levels, and many unworthy people are getting loans.

AI optimism is driving investments, but no tangible ROI for the broader economy.

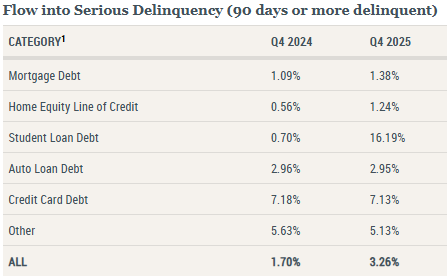

On top of all these, real wage growth is negative, unemployment is increasing, and delinquency rates are rising across the board:

On top of that, there is a great uncertainty as to the policies of the next Fed chair. The administration expects him to cut the interest rates, but he is known as a fiscal hawk.

How would you position this lending business if you were the CEO?

More conservatively, or aggressively? I would surely position more conservatively.

Pagaya is doing this.

This is what the CEO said in the earnings call:

While our data does not indicate consumer deterioration, we have the privilege of being able to pivot our production to focus on prudent and disciplined credit performance across asset classes remain in line with our expectations.

However, we pulled back our exposure to higher risk and less profitable credit deals which have potential for higher relative losses in a downside scenario.

As we mature as a company, we are shifting more and more of our focus to achieve the best long-term outcomes for our stakeholders, and to avoid any downside that could arise from potential tail risks.-Gal Krubiner, CEO of Pagaya

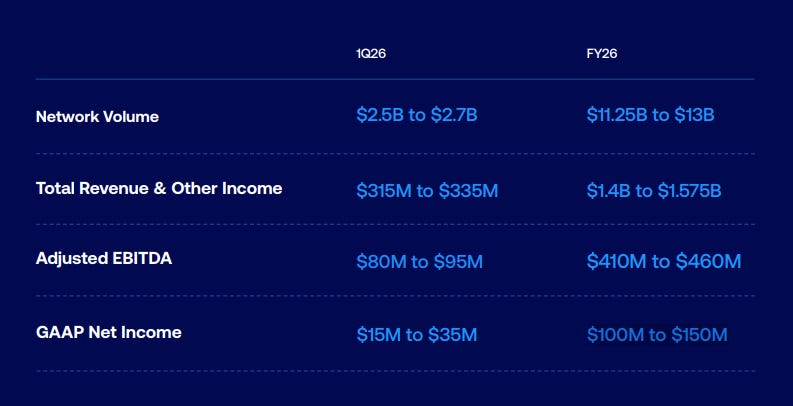

As they are pulling back from less profitable segments and tightening their credit standards, they guided for a lower top-line growth but better profitability:

This is exactly how I would want this business to position itself for the next 12-24 months. So, the fact that the bottom end of their revenue guidance implies just 7% growth against analysts’ expectation of 16% doesn’t really bother me.

My long-term thesis won’t break even if this slower growth rate persists into the future, as I believe I already paid less than a conservative estimate of intrinsic value for this business.

In short, when I look at the business, I see that:

KPIs are improving, signalling fundamental strength.

Business is positioned as I would like it to be.

Its positioning doesn’t break my thesis.

Why would I sell this stock then? I won’t. And I’ll buy even more if I accumulate more cash than I would like to hold.

In short, to get the valuable signals, preserve your sanity, and not be driven by the market, you have to understand the business, know the KPIs, and have an idea as to how the business should be positioning itself given the circumstances ahead. Then, you have to assess whether this positioning aligns with your long-term thesis or not.

This is how you read the earnings rationally and ignore the noise.

🏁 Final Words

I hate earnings seasons because they make so much noise.

The secret of being a good investor is being able to disregard the noise, believe in your own knowledge, and concentrate on what matters.

To do this, you have to internalize a few things:

A single earnings print rarely gives a valuable signal.

You must have a deep and independent knowledge of the business and circumstances that may affect it to get a signal.

You must have an investment thesis so you can know whether a signal breaks the thesis or improves it. Not all negative signals are thesis breakers.

Take Pagaya. Slowing growth is a negative signal in and of itself, but when thought in the context of the business’s previously high markdowns and economic uncertainty ahead, it’s a positive signal that says that the business is committed to not repeating old mistakes again. It’s hormesis.

Please stop stressing yourself over single earnings prints. Know the KPIs, ask yourself whether they are moving in the right direction. If not, ask yourself what the likelihood is that deterioration will be permanent? You may not know this right away, but you’ll likely have to follow a few more reports; but this is what being an investor takes.

Even when there are negative signals, and they may be permanent, you should still assess whether they break your thesis or your valuation is already conservative enough to tolerate it.

It’s very hard to understand all this from a single print, so don’t be so harsh on yourself. Look at the trends rather than point-in-time numbers. Get yourself some sanity while everybody else goes insane.

Otherwise, you’ll always be dependent on what the market decides about a stock. And I know nobody who followed the market and ended up doing better.

My sincere recommendation to you is to start hating earnings seasons.

The more you disregard point-in-time prints and base your analysis on long-term trends, the better you’ll do. I sincerely believe this.

Ah, Dr. Erkin, you’re misleading us. That degree’s actually in Psychology! Deep deep deep competitive Psychology!

Love the Pagaya example. They are reducing risk, which is why I’ll add more shares this quarter. The report wasn’t excellent but simply good. There are reasons to trust management.