AI Energy Trade: Thematic Investment Thesis and Top 20 Stocks

Energy is the real bottleneck for scaling AI and these 20 companies are well positioned to be the category winners.

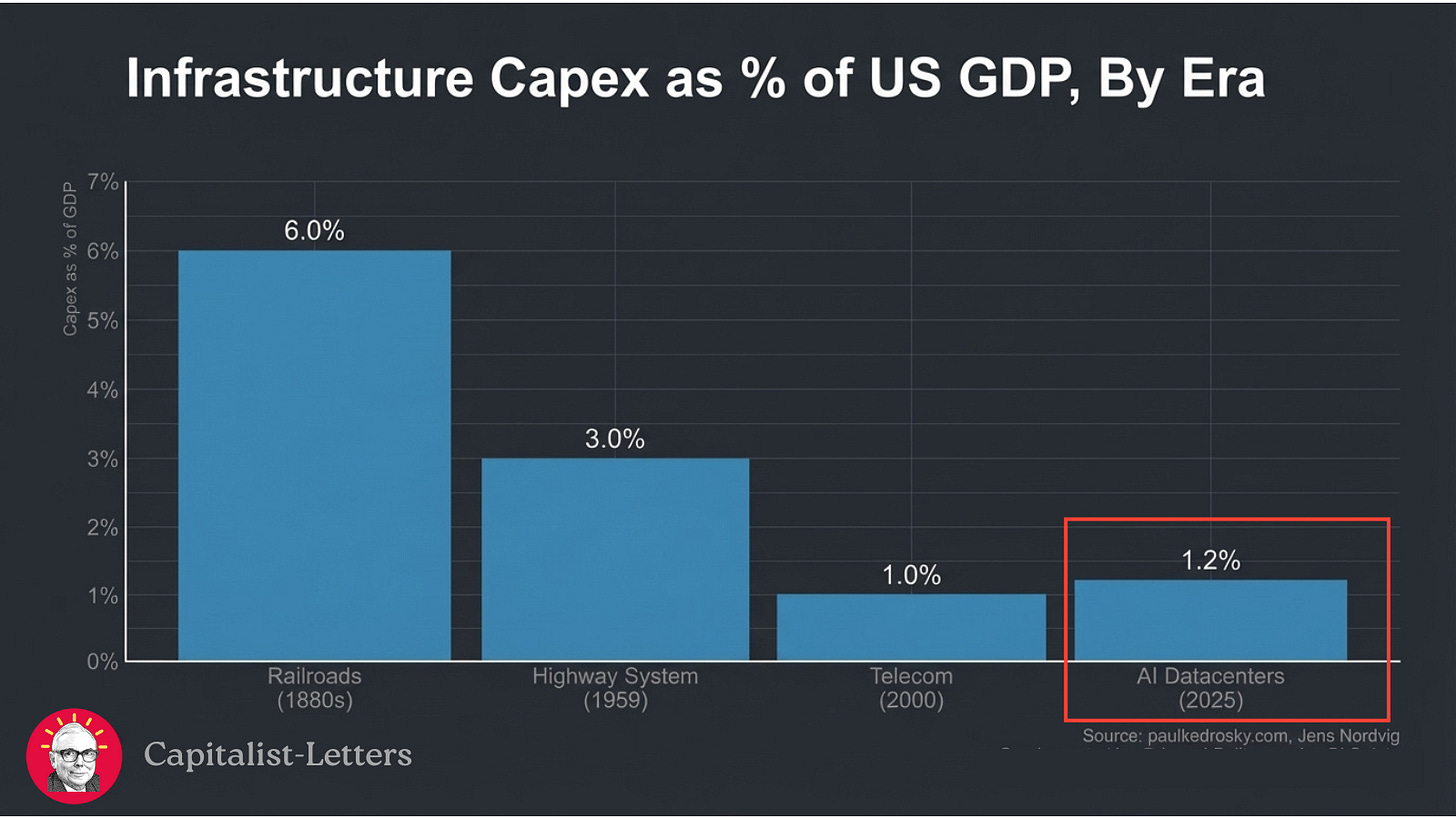

All the great technological breakthroughs require massive infrastructure investments.

Think about the invention of the steam engine.

It enabled the industrial-scale production, but reaching there required investing massive amounts in building railroads for the transportation of raw materials and industrial output at scale.

That wasn’t different for the Internet.

Telecom providers invested outrageous amounts in subsea cables and telecom towers so that the Internet could spread globally and enter literally every house.

Now, another transformational technology is being born before our eyes—AI.

It requires a massive data center buildout just like the industrial revolution required factories and railroads, and the internet required cables and towers.

We are already spending more on building data centers than we did on the internet infrastructure:

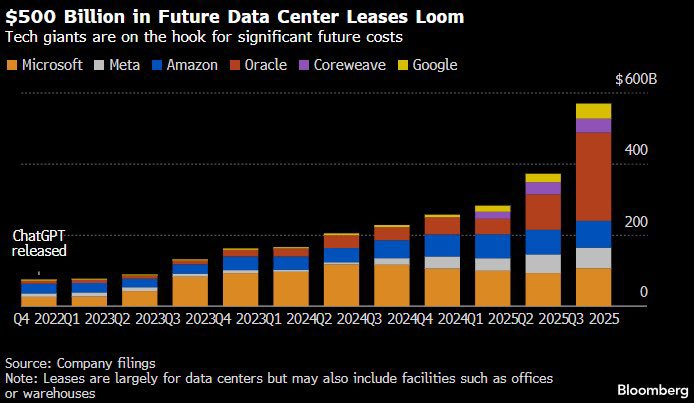

The speed of the buildout is neck-breaking.

Back in early 2023, the 6 biggest hyperscalers had accounted for $50 billion worth of data center leases. As the demand spiked, this number has gone up above $500 billion this year and is nearing $600 billion. This is in addition to the capacity they own by themselves.

In short, the scale of the data center buildout is massive.

When any demand exceeds the supply by this large a margin and forces a rapid and massive capacity buildout, we tend to hit many bottlenecks, as the supply of the critical inputs generally doesn’t scale as fast as the demand.

From early 2023 to recently, cutting-edge chips were the main bottleneck, as Nvidia GPUs were undisputed, and alternatives were way behind in hardware performance. As a result, we have seen Nvidia monopolize the industry for the last 3 years. It has always had more demand than it could meet.

This is changing now.

AMD has largely caught up with Nvidia in terms of hardware performance, and Google is preparing to sell its TPUs to third parties. Amazon’s Trainium has also proved strong, as Anthropic’s giga-watt-scale Trainium cluster has recently become online. Aside from them, many other companies are building their own AI chips in collaboration with Broadcom and Marvell, and TSMC rapidly expanded its manufacturing capacity to meet the demand.

Thus, it’s now clear that the hyperscalers and developers can fill their data centers with the cutting-edge accelerators as fast as they can build them. Chips are no longer the main bottleneck.

What’s the bottleneck now? It’s energy.

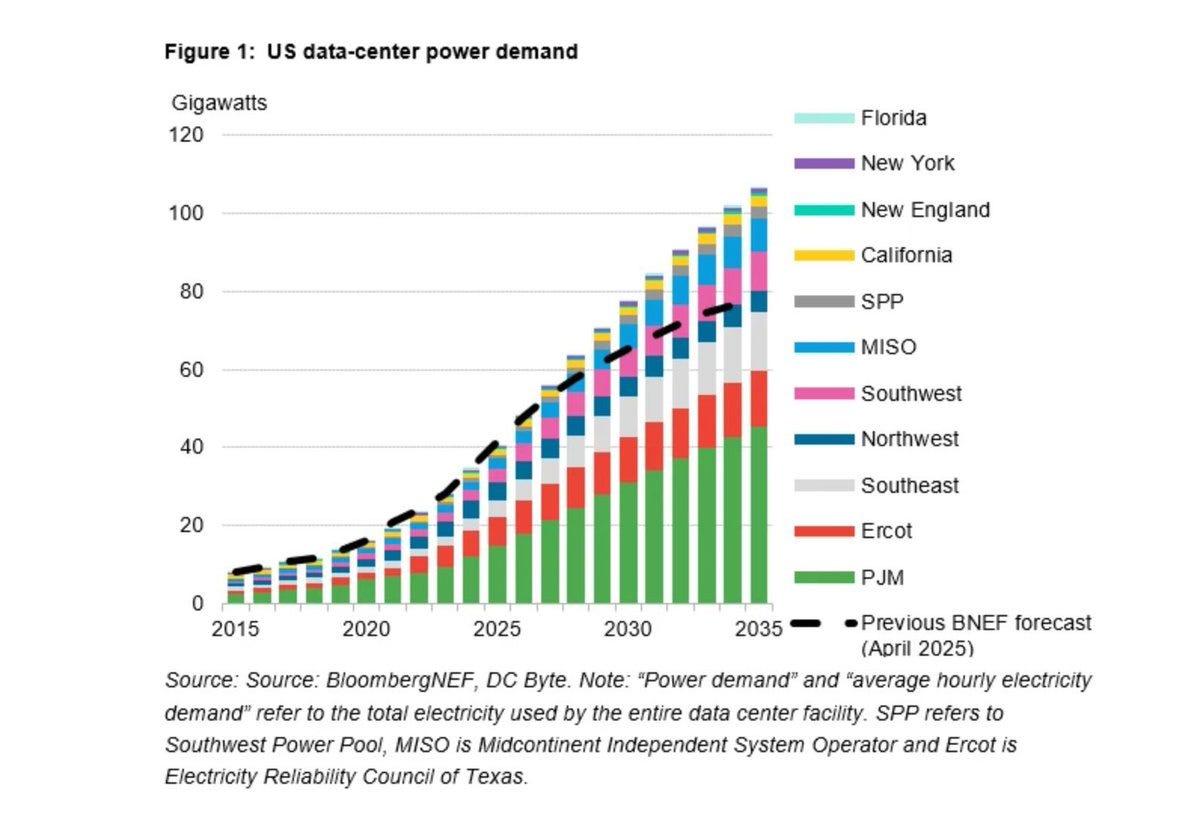

Power demand from data centers is skyrocketing:

Bloomberg predicted that the power demand from data centers would double by 2030 just this summer; it’s been only a few months since then, and they have already revised their prediction: They are now predicting that the demand will nearly triple.

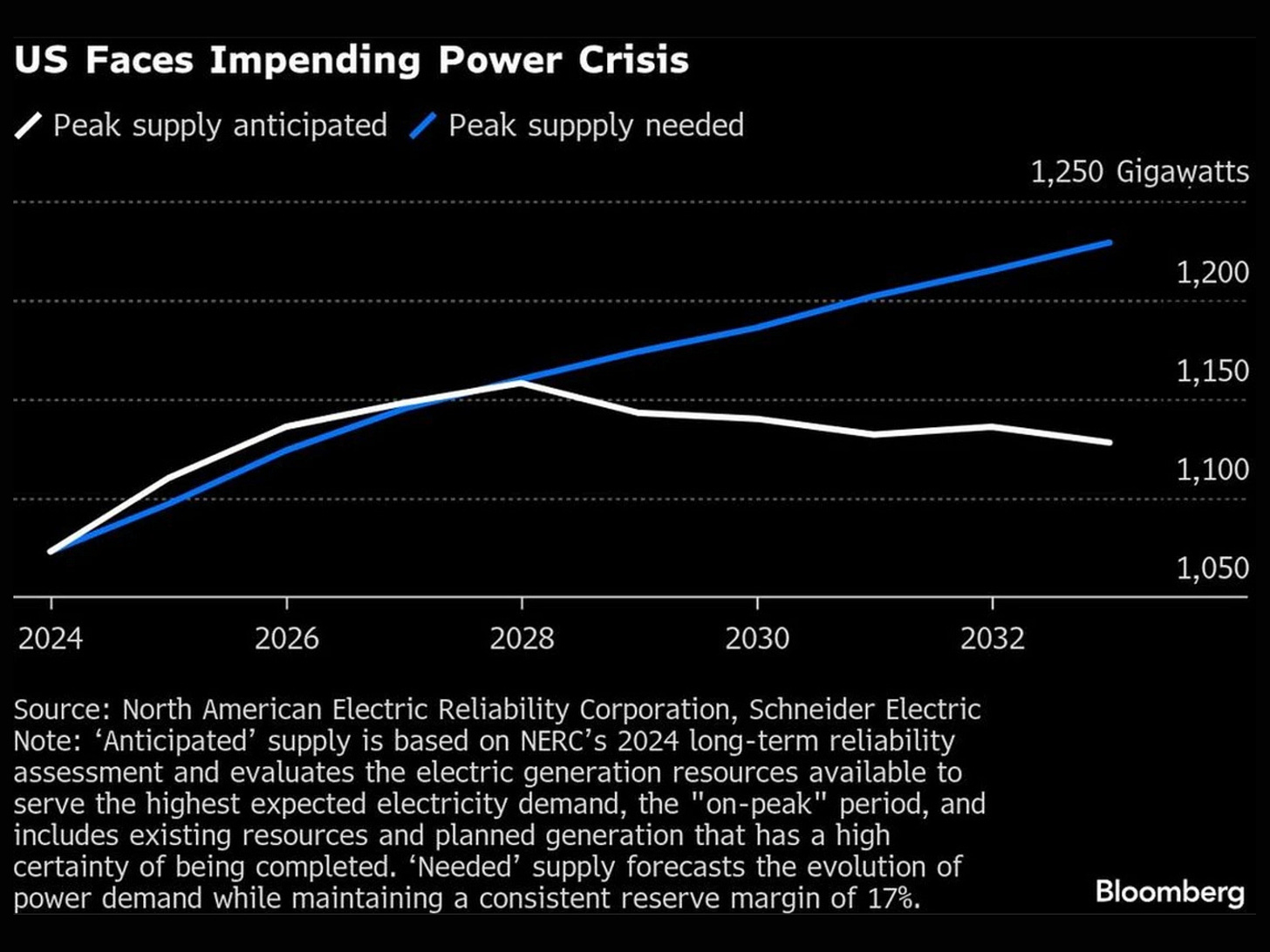

However, it’s not as easy to add new power capacity as it is to ramp up the chip supply. There are significant regulatory and operational hurdles. Thus, Morgan Stanley predicts that the US may see as much as 36 GW power shortfall by 2028.

According to Bloomberg, the gap may widen to 175 GW by 2033:

This means that the industry will be supply-constrained for the next decade, and critical input providers, especially those that are exposed to the data center boom, will have secular tailwinds.

Despite the supercycle of growth ahead, many investors haven’t started rotating into energy yet. They are still chasing the neo-clouds and data center developers, thus valuations in the energy trade are still reasonable. Thus, there is a great opportunity in the energy trade for investors who put time and effort into discovering and understanding the stack.

We’ll do exactly this today:

We’ll first discover the ways of powering a data center.

We’ll then identify the bottlenecks in the infrastructure stack & the industry.

Finally, I’ll present a thematic investment basket of 20 companies that control key bottlenecks and are therefore well positioned to benefit from the coming demand boom.

So, let’s cut the introduction and dive deeper into the AI energy trade.

How To Power A Data Center?

Before diving deeper into how data centers are powered, let’s briefly touch on why data centers are so power hungry and understand what drives the demand.

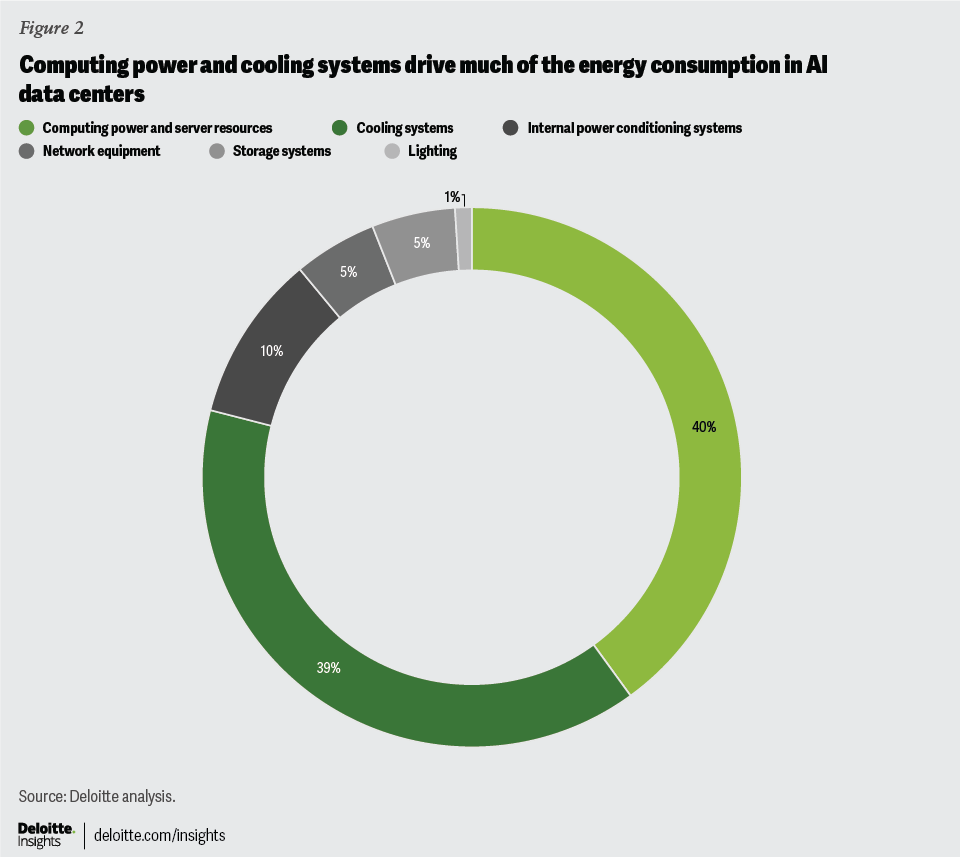

In a modern data center, there are two main drivers of energy demand:

Hardware to generate compute, i.e, chips and server systems

Cooling systems

These two account for nearly 80% of the power consumption of a data center. The remaining 19% is consumed by network equipment like routers and switches, power conditioning systems like voltage stabilizers, storage equipment like hard drives and network drives. Finally, lighting accounts for 1% of the consumption.

A single H100 GPU draws approximately 700 watts under load—roughly the same as a microwave running continuously. But that's just the chip. Once you account for cooling, networking, and power distribution, each GPU requires 1.3 to 1.5 kilowatts of total facility power.

Today's hyperscale AI data centers range from 30,000 GPUs for smaller training clusters to 200,000 GPUs at the frontier, with the industry rapidly scaling toward million-GPU facilities. Even if we assume that an average site will take 100,000 GPUs, this means 130 to 150 MW of power capacity.

For reference, 130-150 MW is enough to power roughly 100,000 homes.

In plain English, an average hyperscale data center consumes as much energy as a small to mid-sized US city like Syracuse or Fort Lauderdale.

According to S&P Global projections, the US has 73 GW of data centers in the pipeline by 2030, while Bloomberg estimates around 50 GW incremental capacity for the same period. This is the equivalent of building over 300 new cities, each with more than 100,000 homes, in the next 5 years.

How can you power a single facility that consumes as much energy as a mid-size city?

When we distance ourselves from the essence of the topic and try to explain it by looking from above, it gets unnecessarily complicated. So, let’s take a step back and assume the role of a data center developer. Imagine you are developing a hyperscale, 100 MW data center for AI workloads. What would be the first step in powering the data center?

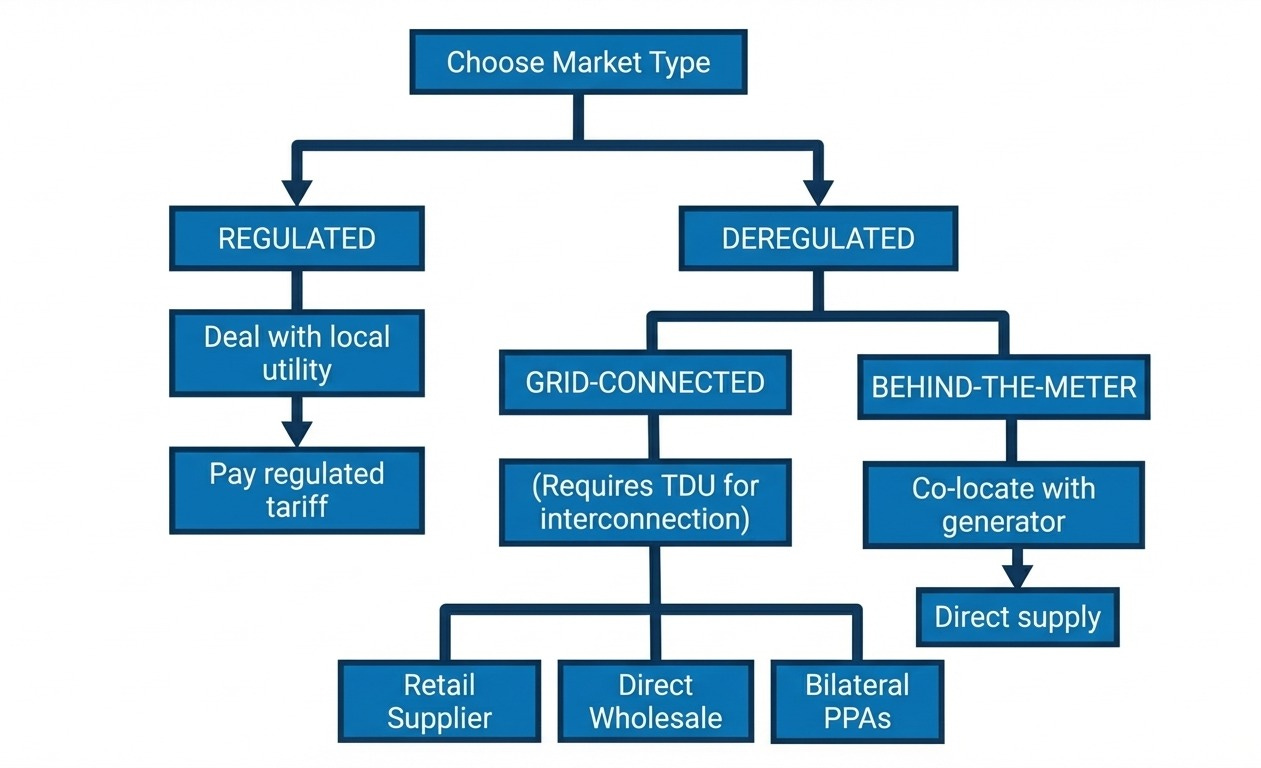

It would be picking the market.

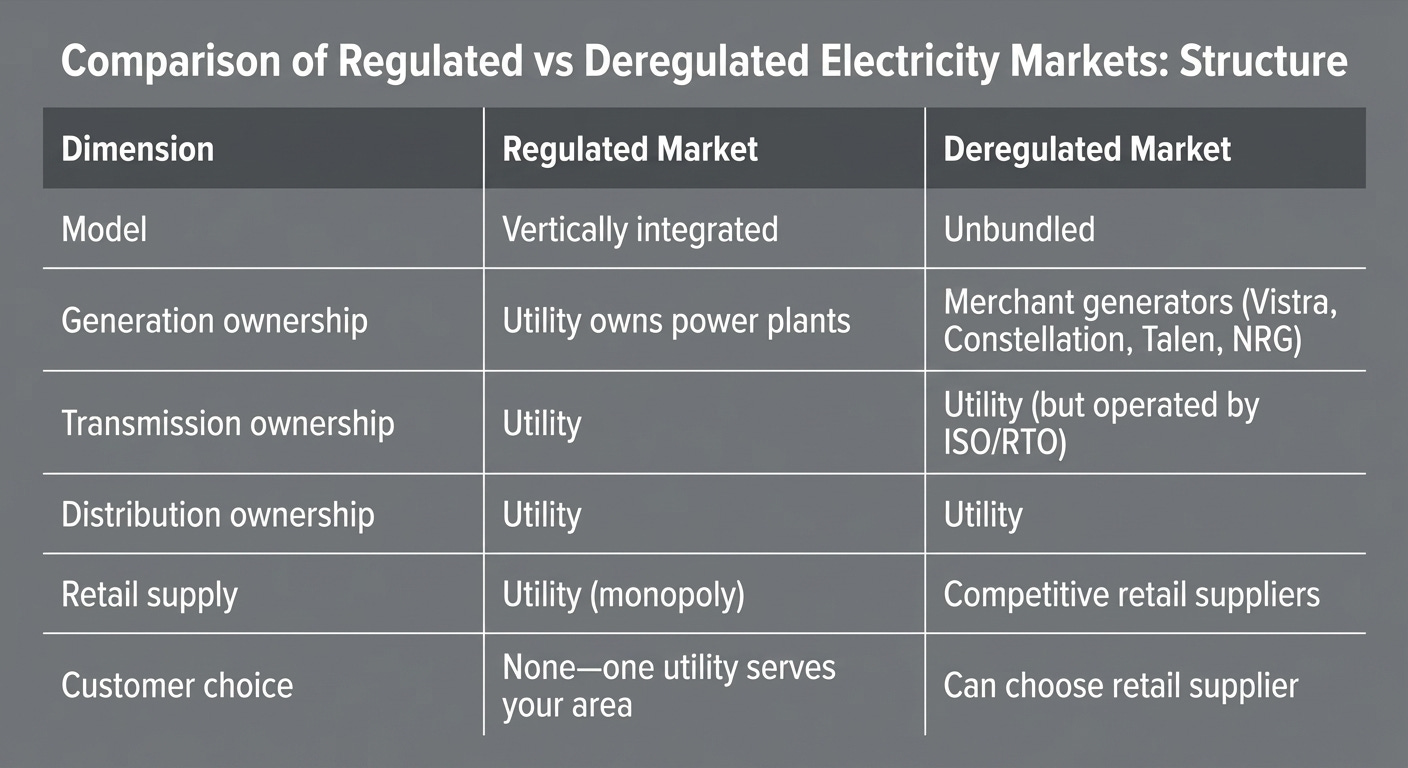

There are two types of markets for power: Regulated and deregulated markets.

What the hell is the difference?

In regulated markets, utilities are vertically integrated monopolies.

They own power plants, transmission lines, local distribution, and retail supply. Customers have no choice; they must buy from the monopoly. In exchange for this monopoly position, utilities accept an obligation to serve everyone in their territory who demands power, and their returns are regulated by the state public utility commission (typically 9-11% return on equity).

In deregulated markets, the electricity system is unbundled.

Independent generators own power plants and compete to sell into wholesale markets operated by grid operators like PJM and ERCOT. Transmission and distribution remain with regulated "wires-only" utilities. Retail supply becomes competitive, and customers can choose their electricity provider. Power producers earn market-based returns, not regulated rates, meaning they can profit handsomely or lose money depending on prices.

For a data center developer/owner, the choice between a regulated and deregulated market comes with trade-offs:

Regulated markets are simple as there is an obligation to serve, and prices are stable and foreseeable through regulated tariff structures approved by Public Utility Commissions (PUCs). However, there is no flexibility or choice.

In deregulated markets, there is flexibility and alternative suppliers, so prices may be lower; however, operational complexity is higher as buyers must manage their own power procurement—choosing suppliers, negotiating contracts, and hedging against price volatility, etc.

So, if we choose a regulated market, it’s simple—we deal with the public utility in that state, get the power from the grid, and pay the regulated tariff. Single decision and we are done.

However, if we pick a deregulated market, we need to make more decisions.

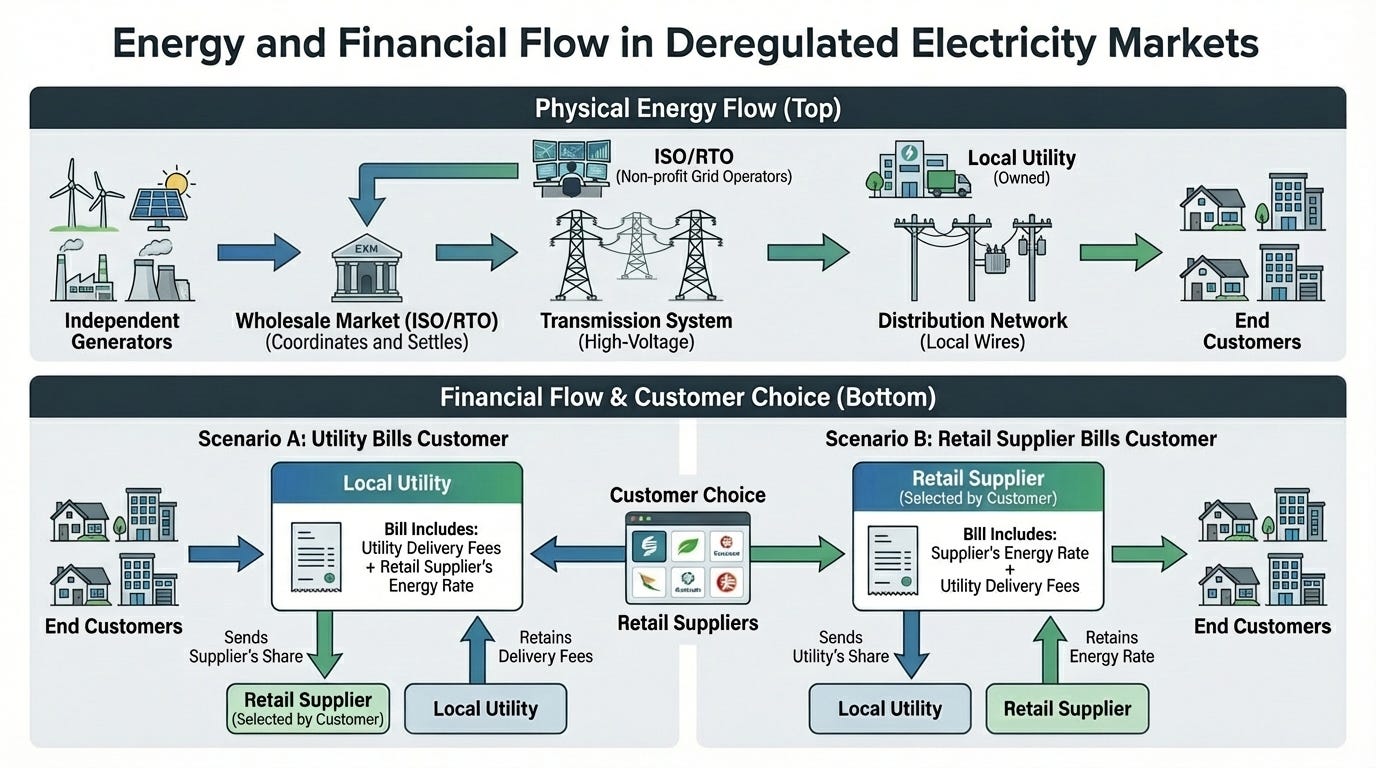

Now, let’s take a step back and remember that functions are separated in deregulated markets:

There are independent power producers supplying power to the market.

Utilities own high-voltage transmission, but it’s operated by non-profit grid operators (ISOs/RTOs) to balance supply and demand.

Local wires (distribution) are also owned by utilities.

Retail suppliers buy power from the wholesale market and sell to end customers. Customers can choose from different suppliers.

In some markets, the local utility sends the bill. When a customer picks a retail supplier, it notifies the utility, and the utility applies the supplier’s rate plus its own delivery fees to your account. When you pay, the utility sends the supplier’s share to them.

In other deregulated markets, the retail supplier sends the bill. They apply the local utility’s delivery fees to your account. When you pay, the supplier sends the utility’s share to them.

From the bird's eye view, the whole flow looks like this:

In this fragmented market, the first decision any buyer should make is how they want to procure their power. There are two alternatives:

A. Grid Connection: Buy power from the grid through various arrangements.

B. Behind-the-meter arrangements: Co-locate next to a power plant, get direct supply.

Now, let’s take these paths one by one and see the options in each path:

➡️ Grid Connection in Deregulated Markets

Here we have three options:

A1. Retail Supplier

You can pick one of the retail suppliers who buy power from wholesale markets and sell to the end users.

You basically pick the supplier, negotiate your contract, and the supplier handles the procurement and delivery. You pay one bill that includes transmission fees for the utilities.

It’s a simple process, but it could be expensive because we are paying margins to retail suppliers that are actually middlemen.

A2. Direct Wholesale Market Participation

You can register with the grid operator, build a trading/procurement capacity, or outsource it and thus buy your power directly from the wholesale markets days ahead. You pay delivery fees separately to the local utilities.

This could yield the lowest power cost as there is no middleman, but it’s an insanely complex operation. It’s almost like building a retailer-supplier business just for your operation.

A3. Bilateral Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) with Generators

In this system, you basically buy the capacity directly from the power plants and pay the utility separately for delivery.

The main difference from buying in the wholesale market is the price certainty. In the wholesale market, you pay the market price; in PPA, we pay the negotiated price.

It’s simple. Three options, all require you to connect to the grid, so you pay for delivery. In behind-the-meter arrangements, you don’t connect to the grid. The flow meter in the grid never works for you, and you pay nothing to the utility.

➡️ Behind-the-Meter Arrangements in Deregulated Markets

In this path, you physically locate your data center adjacent to a power plant and receive direct supply. The power comes to your facility without ever hitting the grid; this is why it’s called behind-the-meter.

For this model to work, you need to acquire a land adjacent to the power plant and build your data center there. However, you still need a grid connection for backup, as data centers require high uptime.

This method allows you to skip transmission costs and avoid grid constraints, but it again brings elevated operational complexity, though still simpler than the direct wholesale participation option in the grid connection path.

In short, the decision tree looks as follows:

Now that we understand the general structure, we can look deeper and locate the bottlenecks in each path, as the companies occupying strategic spots at these bottlenecks will experience skyrocketing demand for the next decade and thus present great opportunities for investors.

Bottlenecks for Powering Data Centers

The first thing you should understand is that there is no single perfect energy market for data centers. Each path has its advantages and disadvantages.

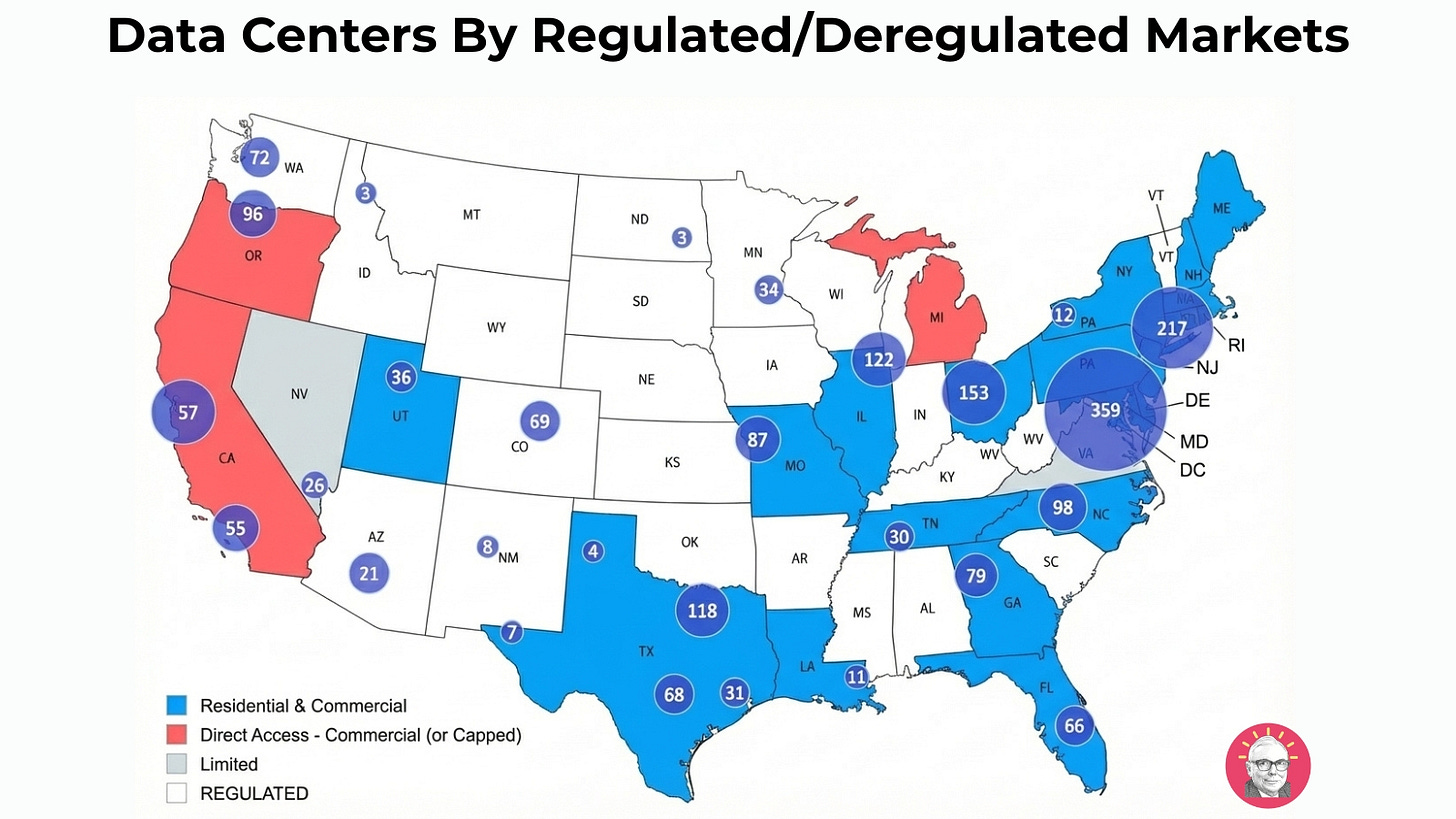

As a result, data centers are scattered across the regulated and deregulated markets:

In the map, you see another type of market: Limited.

There is nothing complex about it. It basically means wholesale is deregulated, while retail supply is regulated. If you want to buy wholesale, you can freely buy from the grid. But if you buy retail, you deal with a monopoly. Virginia and Nevada are limited markets.

You see that data centers are concentrated in Northern Virginia. This was because Ashburn is where early internet exchange points clustered; so network effects compounded; don’t think it had something to do with regulated/regulated/limited market status.

As we have also clarified this, now let’s look at each path to see the bottlenecks.

➡️ Regulated Markets

As we explained above, the path in the regulated markets is simple—you want the capacity, and the utility is obligated to provide it as it’s a monopoly.

This applies to retail supply in limited markets, too, as retail supply in those markets is also monopolized.

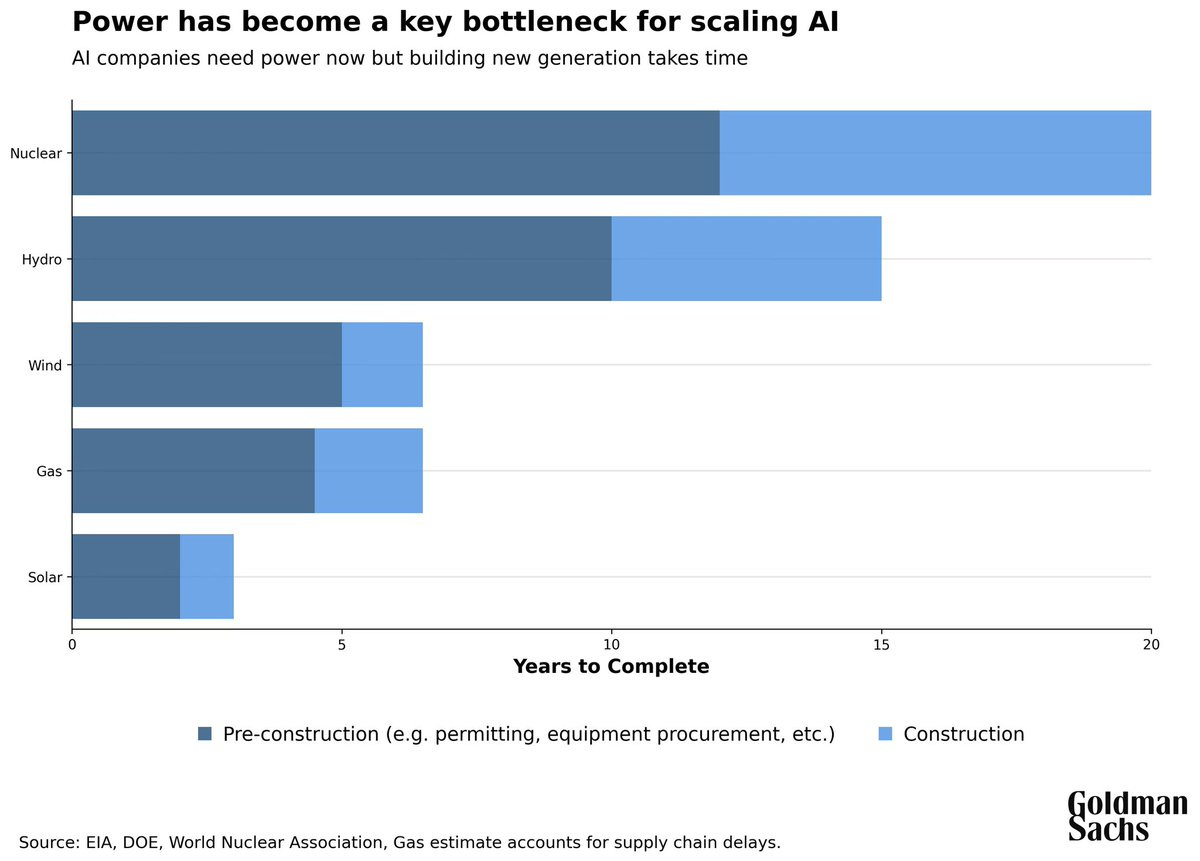

This obligation to provide makes regulated markets attractive, but it also creates a bottleneck. The essence of the problem is that it takes a long time to build a new generation and transmission.

This means that even if you can ramp up the generation in the existing plant, if the grid is at full capacity, you can’t deliver it to the grid, and customers can’t load the grid to get their power.

If the generation capacity is maxed out, you need to build both new generation and upgrade the grid to handle them. This takes an insane amount of time. Even adding new capacity alone takes years, as you see below, and then you have to wait several more years for the grid upgrade.

When power demand in a regulated market increases, the utility can cover it to the degree that existing generation and transmission capacity allow. However, when the grid reaches capacity—particularly transmission—we hit a bottleneck.

This is why Dominion Energy in Virginia now has wait times exceeding 7 years for large projects. Their transmission lines are full. They are upgrading the grid, installing new wires, and building new plants, but it takes time. This is why data center projects are going to other markets where there is available production and grid capacity.

This creates opportunities in:

Utilities with available grid capacity (generation AND transmission) as they will attract data center demand.

Companies in the business of building & upgrading the energy infrastructure, especially the grid.

Energy storage, as it takes less time to build new renewable power plants, but you need utility-scale storage there to optimize generation and manage intermittency.

In short, the big bottleneck in regulated markets is the grid capacity, and then the generation. For now, it looks like transmission is a bigger issue than capacity, according to Dominion Energy. This redirects the demand to regulated markets with enough available transmission capacity. And then, whenever the generation is the issue, it makes sense to resort to renewables as they are faster to build, but they need utility-scale energy storage, which creates opportunities in storage.

➡️ Deregulated Markets

People tend to make it so complex with deregulated markets, as there are many independent players. However, if you start thinking from the buyer’s perspective, it is not that hard to see the bottlenecks.

We have seen that buyers essentially have two options in deregulated markets:

Grid connection

Behind the meter arrangements

If you choose grid connection, regardless of which one of the three available paths you take, the bottleneck is the same—generation and grid capacity.

Remember, we are in a deregulated market, so power plants are essentially competing to provide capacity. Regardless of which path you take, that capacity has to come from an independent generator, as there is no obligation to serve. Thus, capacity can be a significant bottleneck.

Second, regardless of which path you pick and which supplier you deal with, you need to connect to the grid to draw power. Thus, as the load increases, the existing grid needs to be upgraded, and new high-voltage and local transmission should be installed to extend capacity to new sites. This requires significant infrastructure investment.

So, bottlenecks here are essentially the same as in the deregulated markets: Generation and grid capacity.

The opportunities due to upgrades needed in the grid are essentially the same as in regulated markets; however, the opportunities created by the capacity constraints are different. Remember that capacity constraints in regulated markets push buyers to other markets. In deregulated markets, it pushes buyers to other power producers in the same market.

Thus, the bottlenecks for the grid connection in deregulated markets create opportunities in:

Power generators

Infrastructure enablers

Energy storage again, as renewables are the fastest way to add new capacity, regardless of the market

Let’s now turn to behind-the-meter arrangements.

It’s actually very simple, as we have established the fundamentals pretty strongly.

In behind-the-meter arrangements, you don’t need to deal with the grid, so it’s not a problem. However, you still find a plant that has the capacity to sell to you, so it’s still an issue. Plus, given that you need land adjacent to power plants, land itself can also be the limiting factor here.

So, in behind-the-meter arrangements, the bottlenecks are: Generation capacity and land availability.

However, note that power producers generally own the land adjacent to their plants, so betting on them actually captures the opportunity in the land. What’s more interesting here is the land well well-positioned for power generation on site because they have access to water and fuel supply. There is a great opportunity there, too.

Here we have it, the list of businesses that’ll benefit massively from these bottlenecks, as they are strategically positioned to address those bottlenecks:

Utilities with available capacity

Generators in deregulated markets with available capacity

Enablers, i.e, grid infrastructure players, fuel & pipeline owners

Owners of the lands that are strategically positioned for power production on-site.

I have identified 20 companies that are well-positioned to experience an explosion in demand. This is my thematic basket for AI energy trade.

Below, you’ll find:

Names for each category and a quick introduction to their business.

Full basket with target allocations for each company.

5-year price targets

Backtest shows this basket returned 293% since December 2020, outperforming the S&P 500 by almost 19% annually.

(This is based on equal weighting)

Given that we are just in the early innings of the skyrocketing power demand, I think the basket can perform similarly in the next 5-10 years.

📊 Here Is Our Full Thematic Portfolio For Energy

I have divided the portfolio into categories based on the bottlenecks.

Categories and target allocations are as follows:

Regulated utilities, 21%

Independent power producers, 21%

Infrastructure players (enablers), 38%

Storage, 10%

Land, 10%